The deeds of great men and women are the building blocks of history. Even in ancient times and pre-historic societies, the lives of outstanding people have been of unending fascinations to chroniclers and griots.

In traditional African societies, oral traditions are meticulously passed down from generation to generation, detailing the deeds of national heroes and the precepts derivable from their lives of sacrifices and heroism.

In Nigeria, access to the written words has made the quest to write about the deeds of past leaders easier and faster. Even in modern times, biographies and autobiographies remain central to the vocation of the historian in reconstructing the past and setting agenda for the future.

From the cognomen and panegyrics of past heroes and heroines one could discern the panorama of the past. In the last 700 years when foreigners, especially the Arabs and Europeans have been active in Africa, our people have moved from orally documenting the stories of the society, the community and the nation to documenting in writing the histories and deeds of outstanding individuals.

Among African nationalists of the 20th Century, biographies and memoirs were also part of the weapons of the struggle. One notable example was Mzee Jomo Kenyatta’s autobiography, Facing Mount Kenya. It was a widely acclaimed book across the continent on the Kenyan struggle against British colonial rule and the stealing of the African land for the white farmers.

Another perspective was later provided by the thrilling memoir of Kenyatta’s first vice-president and veteran nationalist, Jaramogi Odinga Odinga in his seminal work, Not Yet Nhuru.

Kwame Nkrumah’s autobiography’s Ghana, is of the same evocative template as Kenyatta’s book. Nkrumah’s book is on the transformation of the colonial territory, the Gold Coast, into the independent country of Ghana.

It also tells his role in the struggle and his personal life journey from Ghana, to the United States and returning to join the struggle with other nationalists. Dr Kenneth Kaunda, who led the nationalist struggle in Zambia, wrote Zambia Shall Be Free, which was adopted an English literature text book for secondary schools in several African countries.

In more recent times, Nelson Mandela’s autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, is a monument to the historic struggle against the apartheid regime in South Africa and the central role of Mandela in that struggle.

Nigerian nationalist leaders who fought against the British were also mindful of putting their stories on paper. The three titans who led Nigeria to independence from British rule all wrote their biographies. Chief Obafemi Awolowo’s Awo, is an inspiring autobiography about a man who rose against many odds from a humble beginning to prominence and personal fulfillment. Azikiwe’s daring adventure, recorded in My Odyssey, in search of the proverbial Golden Fleece when he travelled to the United States almost ended in tragedy. Yet he triumphed against all odds to make pioneering impacts in journalism both in Ghana and Nigeria before he forged into politics emerging as the leading nationalist of his generation.

In My Life, Bello tells the story of his journey from the rural Rabbah in Sokoto to become the titan dominating national politics. Yet all these could have been aborted when, to attend secondary school in Katsina, Bello had to travel on foot and only narrowly escaped being eaten by lions!

The biography is the sword in the hand of the story-tellers to reconstruct the past and create a path for coming generations. In Nigeria, biographies have been used to calibrate aspects of our history and deliberate on sociological phenomenon.

For us in Nigeria, three national events have especially dominated the attention of biographers of the 20th and early 21st Centuries. These three epochs were the struggle against British rule and its immediate aftermath, the Nigerian Civil War and its consequences and the struggle against military rule and thereafter.

The generation of the nationalists who led Nigeria to independence continues to attract many books. There is the seminal work, A Right Honourable Gentleman – the Life and Times of Alhaji Sir Abubakar Tafawa-Balewa written by the British scholar, Trevor Clark.

There is also Ahmadu Bello by John Paden, another British scholar. Akinjide Osuntokun’s, Chief S.L. Akintola: His Life and Times, Alan Feinstein, African Revolutionary, The Life and Times of Nigeria’s Aminu Kano, Adekoyejo Majekodunmi’s My Lord What a Morning and Memoirs: Chief H.O. Davies, by Chief H.O. Davies are some of the books that open the vistas to the politics of the First Republic.

We also have the Fugitive Offender by Anthony Enahoro, The Trial of Obafemi Awolowo, by Lateef Jakande and My March Through Prison by Obafemi Awolowo as some of the biographical works written about the First Republic.

Other books on the First Republic and its leaders include, Power Broker: Sir Kashim Ibrahim, by Akinjide Osuntokun, Resilience in Leadership: Alhaji D.S. Adegbenro, by Olajire Olanlokun, My View of the Coin, A participant Accounts of the Politics of the First Republic, an autobiography of Chief Joseph Oduola Osuntokun, Power and Governance, the legacy of Dr Michael Okpara by Onyema Ugochukwu

Professor Saburi Biobaku two books, When We were Young and When We Were No Longer Young, gives us the insight of a bureaucrats and intellectual to the politics and sociology of Nigeria in the last decades of British rule and the post independence era. Simon Adebo, Nigeria’s first Permanent Representative at the United Nation, gave an account of his tour in Our International Years. Emeka Anyaoku, first African Secretary General of the Commonwealth gives an account of the enduring influence of the institution in his work, The Inside Story of the Modern Commonwealth.

Anyaoku’s biography, Eye of Fire, by Phyllis Johnson provides further insight into the institution that Anyaoku served for several decades. Another giant on the international scene, the first Executive Secretary of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, ECA, is the subject of Sanmi Ajiki’s A Rainbow in The Sky of Time: Adebayo Adedeji.

While many of the First Republic leaders wrote autobiographies, the Civil War era generated more memoirs. The man who opened the floodgate was General Olusegun Obasanjo, the war time commander of the Third Marine Commandoes Division who concluded the Civil War in 1970 when he received the surrender of the Biafran High Command.

Obasanjo’s My Command, has remained the touchstone book for the Nigerian War literature. Many authors among those who saw action during the Civil War or the preceding coups wrote about their experiences.

Among the authors are Alexander Madiebo’s The Nigerian Revolution and the Nigerian Civil War, Ralph Uwechue’s Reflections on the Nigerian Civil War and Adewale Ademoyega’s Why We Struck. Colonel Alabi Isama’s Tragedy of Victory provides a fresh insight to the Civil War and an alternative view to the pioneering work of Obasanjo’s My Command.

The politics of military participation in politics has attracted a lot of interests. Standing out is Obasanjo’s trilogy, My Watch, a thrilling memoir about his tour of duty from the Civil War era to his experience as an elected President. This is a follow-up to his Not My Will and the book, Nzeogwu.

In a class of its own is Ironside by Chuks Iloegbunam, a comprehensive look at the first coup and the 200 days reign and tragic end of Nigerian first military ruler, General J.T.U. Aguiyi-Ironsi. It was the same period of national vicissitude that is captured in Peter Ajayi’s Fajuyi: His Last Days, a gripping narrative about the assassination of Lieutenant Colonel Adekunle Fajuyi, the first military governor of the West and General Ironsi, Nigerian first military ruler who was visiting Ibadan at the time.

Major Debo Basorun’s Honour for Sale discusses the power play in the court of General Ibrahim Babangida, especially concerning the assassination of the first Editor-in-Chief of Newswatch, Dele Giwa.

In his The Military, Politics and Power in Nigeria: Ibrahim Babangida, Dan Agbese analytical book takes a more sympathetic view of military government. Joe Garba’s Diplomatic Soldiering, is the author’s memoir about his involvement in the coup that brought General Murtala Muhammed to power in 1975 and his subsequent service as the Nigerian Commissioner (Minister) for foreign affairs. In Gowon, Isawa Elaigwu renders an excellent account of General Gowon’s life history.

Ironically, unlike the politicians of the First Republic, subsequent generations of politicians and leaders have produced few compelling books.

Bola Ige wrote The Kaduna Boy and the Politics and Politicians of Nigeria. Chief Michael Adekunle Ajasin also wrote his autobiography: Ajasin: Memoirs and Memories.

Adinoyi Ojo Onukaba wrote an excellent work on the former Vice-President titled Atiku: The Story of Atiku Abubakar. Onukaba is also the author of Olusegun Obasanjo in the Eye of Time.

Femi Ogbontiba wrote the biography of Chief Bola Ige, The Portrait of a Giant: Chief James Ajibola Adegoke Ige.

The subject of Adegbenro Adebanjo’s book, Acts of Daniel, is the former governor of Ogun State, Otunba Gbenga Daniel. Bolu John Folayan wrote Olusegun Agagu, A Political Portrait a biography of the late governor of Ondo State.

Journalists, academicians, judges, people in business, artists and other people have also been subjects of biographies. Some of them have gone ahead to write their own biographies.

Walking a Tight Rope, by Babatunde Jose, the former Managing Director of the old Daily Times relates the thrills and danger accompanying the glamour of leading Africa’s largest newspaper congolomerate in the 1960s and ‘70s.

Kunle Ajibade’s Jailed for Life and Chris Anyanwu, The Days of Terror document for posterity their experience during the dictatorship of General Sani Abacha when they were railroaded into prison for alleged coup plotting. Dare Babarinsa’s One Day and A Story is about his experience in the old Newswatch covering the assassination of Dele Giwa and its aftermath.

Born To Run, the biography of Giwa, is authored by Onukaba and Dele Olojede tracing the life and times of Giwa and his impact on journalism.

The Politics of Death by Segun Adeniyi looks at the last days of President Umar Musa Yar’Adua. Inside Aso Rock by Orji Ogbonaya Orji, is another thrilling insight into the power sanctum of Aso Rock Villa, Abuja, during the era of Abacha. The book also narrated the story of Abacha shocking death in 1998.

Many memoirs provide a tableau of narratives about the Nigerian state, the interlocking of national events in affecting the private lives of individuals and communities.

At the epicenter of this genre are the memoirs of Wole Soyinka, Africa’s first winner of the Nobel Prize for literature who has written many books about his experience, from The Man Died, his prison experience during the Nigerian Civil War to Ake: the Years of Childhood, Ishara and the monumental You Must Set Forth At Dawn.

Oladele Olashore’s Joy of Service, is a different kind of narrative about the interaction of an elite and his native environment, in this case, Iloko-Ijesha where Olashore, a former Minister of Finance, was the traditional ruler.

Sir Olaniwun Ajayi’s Isara Afotamodi, My Jerusalem, is also a memoir about an elite and his native environment. Kalemie, Memoirs of UN Military Observer by Navy Commodore Bimbo Ayuba talks about his hair-raising experience as one of the commanders of the Nigerian military contingent to the Democratic Republic of the Congo as part of the UN Peace Keeping Operation.

In Alfa Jeje, Fassy A.O Yusuf presents us a fascinating biography of Honourable Justice Alfa Belgore, former Chief Justice of the Federation. A Life of Sacrifice by Abdulrahaman I. Sade, is about the eminent physician and teacher, Professor Umaru Shehu.

It is good that it is increasingly becoming acceptable that many of the elites are seeing the writing of their memoirs as part of their legacies and are taking steps to document their involvements in the Nigerian story.

Professor Akinlawon Ladipo Mabogunje’s A Measure of Grace, Ladipo Akinkugbe’s Footprints and Footnotes, Omo N’Oba Erediauwa, the Oba of Benin’s I Remain, Sir, Your Obedient Servant, Akinjide Osuntokun’s Abidakun, Oluwole Komolafe’s Adventures of A Country Boy in The City, Olaniwun Ajayi’s Lest We Forget are some of the success stories in this direction.

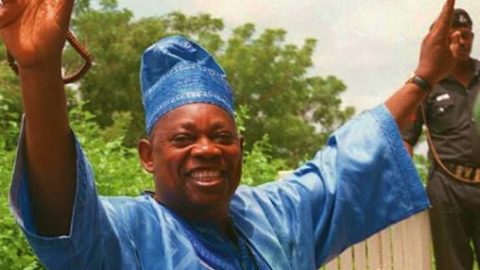

All our leaders who have served at the national level have continued to hold endless fascination to writers who are exploring aspect of their lives. Awolowo has attracted a lot of biographical treatment but not yet a single complete biography. Those who have been threatening to write Awo’s biography for decades now have so far not done so. Okion Ojigbo’s Shehu Shagari, The Biography of Nigeria’s First Executive President is one of the best in the genre.

Many characters and subjects continue to attract the attention of the biographers. Gilbert Gil’s Fela: The Bitch of a Life, throws illumination on the phenomenon of the great Afrobeat king. Albert Agbaje succinctly narrates the story of the late primate of the Church of Nigeria, (Anglican Communion) in his book, Abiodun Lagos: A Blooming Tree in the Desert –Joseph Abiodun Adetiloye. Dillibe Onyeama’s memoir, The Return: Home coming of a Negro from Eton, explores the pain of culture clash.

I Rest My Case – Hon. Justice Umaru Kalgo, by Kelechi Anosike is about the leadership of the Nigerian judiciary and the role of the subject. Sultan Abubakar III, Sarkin Musulmi by Jean Boyd with Hamzat M. Maishanu is the life story of the late Sultan of Sokoto and his role in some of the defining moments of modern Nigerian history.

What is becoming increasingly clear since the return to democratic governance in 1999 is the inability or reluctance of the new power elite to reduce their experience into writing. Unlike leaders of the First and Second Republic, the current leaders prefer to just fade away after leaving office.

Nigerians are still waiting for the memoir of President Goodluck Ebele Jonathan and a definitive book on his predecessor, President Umar Musa Yar’Adua. Few of the governors and ministers who have served since 1999 have written anything of note. One notable exception is Nasir Ahmad el-Rufai’s Accidental Public Servant, a book that continues to attract a lot of positive interest and controversies.

Professor Tunde Adeniran, former Minister of Education also wrote Mission to Germany, about his experience when he was Nigerian ambassador to Germany under President Obasanjo.

While our governments are willing to build statues costing scores of millions, many of our governments and prominent individuals are not willing to encourage the writings of biographies of past leaders. In the city of Lagos, there are statues of past heroes like Beko Ransome-Kuti, Mobolaji Bank-Anthony, Herbert Macaulay, Gani Fawehinmi and Tai Solarin, but few books on them and none commissioned by the government.

Apart from books written by the leaders themselves, there are few books on past leaders. As of now, there are no definitive biographies on either Azikiwe or Awolowo. Tafawa-Balewa and Bello have fared better in this regard.

Lack of interest in intellectual products by the power elite is having a serious negative effect on the general population and the desire to read by the younger generation is declining daily.

Worse than the advancing desertification from the North, there is also an advancing intellectual aridity that is overtaking the national landscape. There is no indication that things are about to change very soon. In Nigeria, the sword of the storyteller is getting blunt.

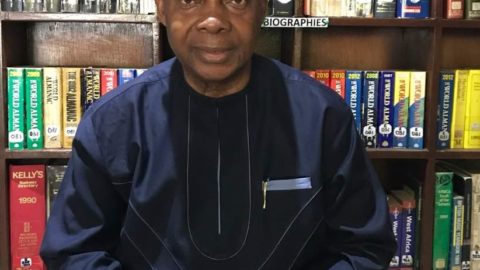

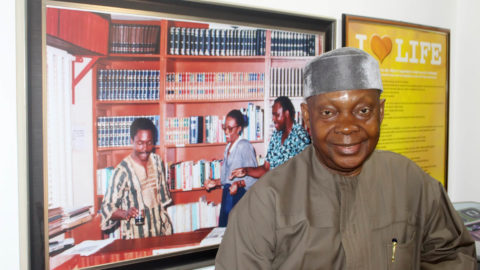

* Dare Babarinsa is a renowned Columnist with the Guardian Newspaper, Nigeria who crafted this piece for the BIOGRAPHICAL LEGACY & RESEARCH FOUNDATION; Publishers of Blerf’s WHO’S WHO IN NIGERIA (Online) edited by nyaknno osso.

Articulated work by committed individuals.