You ain’t seen nothing yet! When Page Seven came out in the

Daily Times, they said it was the ultimate, but I knew it wasn’t.

When Sunday Concord came, they said it was a good paper.

Then Newswatch.

Newswatch is my life and the lives of my colleagues,

And we intend to surprise Nigerians …We will always bring new dimensions to this great project.

INTRODUCTION BY MR. KEVIN EJIOFOR

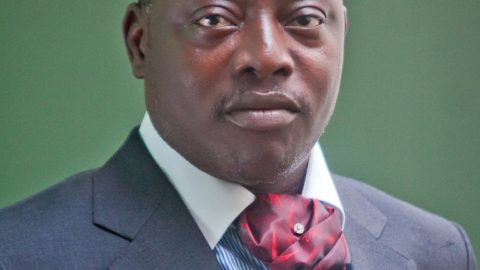

Hello! Yes, this is Just A Chat, and you know, there is something very special or shall I say two things are very special about this programme. One is known: You are there; and the other is having some really wonderful people to talk with. Today, I have with me in the studio a young man, if I may call you so sir. He is a very well-known media personality, Mr. Dele Giwa.

Kevin: Dele, you are welcome to Just A Chat.

Dele: Thank you, Kevin.

Kevin: Well, I called you a young man just now, I didn’t mean to sound, or rather, talk down on you at all. It is just that you are something of a whizz kid in the media circles in Nigeria. How does that feel? You know, you‘ve been here only a short while but everyone knows about you.

Dele: The other day, I was picking my hair and I saw three strands of grey hair, and I said to myself, okay, when these three strands become many enough, people would stop calling me a whizz kid. But it is good to be recognized at a very early age. If you look at your contemporaries, most of them do not get the attention that you get until they are fifty or more. But I feel humbled by the recognition and I see that it means I should work harder.

Kevin: How did you get into the media?

Dele: Into journalism to be specific

Kevin: Yes!

Dele: Aha, I actually (you won’t believe this) wanted to be a chemical engineer or a doctor. In those days, while I was in the secondary school, in the 60s, the popular thing was that you want to be a scientist, an engineer, a physicist or a physician. So I wanted to be chemical engineer. But when I was in form three, my teachers told me, ‘You’re so good in English, why don’t you take a degree in it when you leave school.’ I then became the founding editor of the school fortnightly called The Torch at Oduduwa College, Ile-Ife. And my career in journalism started there and then.

Kevin: Okay, we’ll take on the proper career later. Now that you are talking about your early days, tell me about yourself, where you come from and all that.

Dele: Well, if I were an American, I would say I was born in Ile-Ife, which is where I come from. But I am a Nigerian; I come from where my parents come from. I was born in Ile-Ife by parents of Bendel State origin (now Edo State). My father and mother are from a village near Auchi called Ugbekpe-Ekperi. My father is dead, he died in 1977. My mother is alive. My father and mother had always lived in Ife until my father died and then my mother moved home. So I can’t say I come from Ife. I am from Bendel State (now Edo).

Kevin: Okay, after Oduduwa College, what did you do?

Dele: Ah, I worked briefly, for about six months, with Barclays Bank (now Union Bank). I couldn’t get the figures together, so I eventually moved to the Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria (FRCN). You won’t believe that.

Kevin: NBC (Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation) then.

Dele: NBC, Ibadan, as a reporter under my best teacher forever, Alhaji Saka Fagbo.

Kevin: I see.

Dele: Yes, Fagbo was my best teacher; my first editor and my forever editor.

Kevin: And you left in …?

Dele: I left in 1970 to go the US. I went into Brooklyn College of the City University of New York and took a degree in English. Then in 1974 September, I joined the New York Times as a news assistant, rising to a reporter and then I spent the last six months there in New York with the New York Times at the UN as a staff of the Bureau … at the United Nations.

Kevin: That is something special, I mean to a Nigerian who hadn’t got a US citizenship and so on. Well, that was something special happening to you, being hired at the New York Times. How was it working for that venerable paper?

Dele: I was arguing with a couple of Nigerian students in a library one day. I was looking at the front page of the New York Times when I saw an error and I said, even Dele Giwa wouldn’t commit this kind of error. And they say, ‘there you go again.’ Then I replied: How do you mean there you go again? I can go get a job on that paper. It was a Friday afternoon. They said no way! So on Monday, I got dressed, went to New York Times and got a job.

Kevin: Just like that?

Dele: Just like that.

Kevin: Just because you believed you could?

Dele: Yes, I went there and they said I should write something and I wrote it and the woman said, ‘I never read something like that from a black man before.’ She said, go to the editor. I went to the editor. I started working the next day.

Kevin: Well, okay, I think at this point it is good to stop and listen to your kind of music, wash down what we have heard so far, while I think about what I’m gonna ask you next. What’s your first choice of music?

Dele: I would like Once Again, a number by Earl Klugh from his album called “Wishful Thinking.”

Kevin: Thank you very much. Dele, I would like to know about your period in the New York Times. I don’t want us to dwell on it but for people who said to you, I never read this kind of thing from a black man; that sounds rather condescending. Did you have a good time there and what did you think you took away from the New York Times?

Dele: I have this rebellious streak that I always find difficult to live down. At the time that I was there, the black and the Puerto Ricans, that is, people of yellow skin, were having problems with the New York Times. I came in as a news assistant and it was becoming too long for them to move me to a reporter’s status. So I was the first person who signed the resolution by the minority workers to sue New York Times for discrimination. We won the case, and I got for myself about two thousand dollars and a promotion.

Kevin: A case of rebellion paying off eh?

Dele: It always does, you know.

Kevin: Always does?

Dele: Always does.

Kevin: Okay, after the New York Times what did you do? You came back home?

Dele: No, I met a fellow, a tall, light-complexioned man with a baritone, Dr. Dele Cole, and we struck a friendship. And he said I should come back home. Between him and Dr. Stanley Macebuh, I came home and became the features editor of the Daily Times of Nigeria.

Kevin: Aren’t you lucky? Would you say this was probably one of the best periods of Daily Times in recent history, I personally think so.

Dele: I feel proud that you said so; but I think I was lucky and I believed that I should put in the best I have, which I did, which paid off.

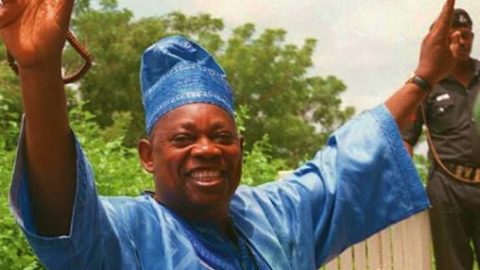

Kevin: And then came the civilian regime and you left surprisingly for a partisan newspaper, at least that was what it was then, Concord Group of Newspapers.

Dele: You see, there was this story done on me by Vanguard a couple of days ago. And the young man, Ely Obasi, who did the story, did something that I consider remarkable. He said I was running away from National Party of Nigeria (NPN) by leaving Daily Times and then ran full force into NPN by going to work for an NPN chieftain, Chief M.K.O. Abiola. I told him, I said to Dele Cole that I was not prepared to leave the Daily Times if he said I should not leave. So it took Abiola at least three weeks to get Dele Cole to agree to release me. I did not leave Daily Times. In fact I had a very big fight with Stanley Macebuh on this because he said by leaving Daily Times I was ditching my friends. But I told him, I must go because I could see that the NPN would take over Daily Times within two months and they would remove Dele Cole and Tony Momoh. And Dele Cole said, ‘okay you can go.’ So I left. I knew that I was going to an NPN paper but I knew that nobody could make me support any party I didn’t want to; not even Chief Abiola.

Kevin: So, why did you leave? Was it for more freedom or money?

Dele: No, not for more money. You see, this is how it went. I went there, I was offered a job. I did not agree for three weeks. They put the pressure on me for three weeks and when I finally agreed, I did not negotiate my salary. I told (Chief Henry) Odukomaiya, who was the managing director, pay me N1, 000 less than what you are going to pay Dr. Doyin Aboaba (now Dr. Doyin Abiola), who was the editor of the daily, the National Concord. I didn’t know what they were paying her, I just said; give me N1, 000 less in annual salary. I knew that if I were in Daily Times they will kill my column and that will mean killing me. Two, they will fire me eventually because I will rebel against it. I knew Chief Abiola would soon see how good I was and would want to keep me on, although he would hate my politics of non-NPN partisanship. So I weighed the coin and to me, Concord was okay. I knew I could survive there.

Kevin: Eventually, you kept repeating in your write-up that Chief Abiola never tampered with your column for one day and you were free to write what you felt like.

Dele: He never did. He would wait for you to publish before fighting. He would never send for you, he never did but we always fought after every column. Oh, yes, we fought on principle. Anyway, let’s leave the Concord and particularly the newspaper alone, I want to talk about the press, the media.

Kevin: When you talk about fighting, talk about NPN and talk about government, there is this view that all the media people, all the newspapers in this country are pro-establishment. They rarely are on the side of the people in spite of all the rebelliousness they seem to exhibit.

Dele: I don’t think it is that simple, it is a very complex thing. You know, we are journalists. You are involved in a certain kind of power structure. The people in power fear you, and they also think they have power to silence you, but because, somehow, by being a public person, your disappearance, either by death or imprisonment, will be known by the people, the government is confused, perplexed, about what to do with you. So they hate to love you, they accommodate you, but by so doing, you become a part of the structure. Yes, then you begin to have dinners and lunches with people in power, and then you can’t come out to hit them anymore. But some of us are aware of these complexities in leadership, so we do not go to these lunches too often or we’ll let them know that if we should come to the lunch, if you do something wrong, we shall hit you and we have credibility because we’ve done that.

Kevin: Okay Dele, I won’t pursue it, because I think we’ve both made our points and we’ll leave our listeners to decide.

Dele: Okay.

Kevin: Okay, now you’re in this new thing called Newswatch, what is it all about?

Dele: Newswatch is a weekly magazine—Nigeria’s weekly newsmagazine. It is medium put together by journalists to provide a haven for journalists to practice without let or hindrance.

Kevin: That is the dream, isn’t it?

Dele: It’s there. You gonna see it every Monday. You saw it yesterday, you’ll see it every Monday and it shall bear after truth.

Kevin: Is there a major or felt need which you think you’ll be serving? This question of a haven where journalists can practice without let or hindrance, is there a compelling ideology behind it which you want to project?

Dele: There is, but that flows from the basic tenet that you must have freedom above self, you then worry about the secondary condition of the society.

Kevin: Okay, Dele, you’re not all about newsprint, articles and so on. Tell me about yourself.

Dele: I am married to Funmi, we are having a baby in February, this month. I have four children, my first son is 18, my second is 10, my third is 7, both of them (second and third) are living in New York with their mother. I have this daughter, who is more than three and my little baby that is just coming.

Kevin: I called you a young man, and I keep apologizing over that. What do you do to keep fit apart from reading and writing?

Dele: I have lived a very active life. I am intellectually busy. I do not worry too much. I believe, if you’re busy—intellectual and physical—you exercise your body and mind. And you’ll probably look younger in the process.

Kevin: We’ll pause again and listen to more music while I gather my thoughts together, as I always say. People don’t know that’s part of the reason we play music. What are we having now?

Dele: This time, I’ll like a title from Evita called Don’t Cry for me Argentina

Kevin: Don’t Cry for me Argentina, forever a lovely music. Dele, it’s a mood setter. Isn’t it? You’ve talked a bit; you’ve used some words in the course of this programme to describe yourself. You’ve talked about being rebellious and you’ve talked about being humbled by fame. You’re talking about being a rebel especially in journalism circles. I have this feeling that the leaders and people in power should begin to dance, in a way; the rebels are a dying breed. What do you think?

Dele: The rebels are a dying breed?

Kevin: Yes.

Dele: No, they live forever

Kevin: I mean in the sense that they cannot achieve much.

Dele: No, they can achieve a lot by intelligent expression of outrage.

Kevin: It’s okay, that’s the kind of thing I mean. You declared the other day in Vanguard that you used to be a mad young man, meaning that the madness is being cut out now and you’re going for the mature approach and so on. That inevitably happens.

Dele: Even when I was a little bit rascally, the maturity never went cold. If I get angry, I will express my anger. Now, I have many years to back-up whatever I say, and people will take me seriously.

Kevin: Isn’t it part of the difficulty for those who fight causes in Nigeria, the media and so on? It seems the nation itself is gradually losing its sense of outrage, we tend to take everything. You fight a cause, make sacrifices and people say that you’re foolish, why is he looking for trouble?

Dele: You know, I did a column when there was this crash in Enugu, the air crash. I did a column called “Nigerians Can’t Be Serious” or something, which I said we’ve lost the sense of national pride; that we need to correct things. I did not say Nigerians have lost their sense of outrage, I believe if we should push the people of this country too hard, they will kick back and you will not like it. I don’t think we have it. If we’ve lost it, then we must give up and go home everyone must go to his village and form a nation there. We dare not bruise ourselves on that. We dare not.

Kevin: Okay, Dele, you are 38 and I said at the beginning that you’re something of a whizz kid. You were talking of being humbled. Does it trouble you sometimes that there is not much more you can do?

Dele: I’ve not done anything. When Page Seven came out in the Daily Times, they said that it was the ultimate but I knew it wasn’t. When Sunday Concord came and we were able to live down Abiola’s NPN partisanship, they said it was a good paper, nothing more was gonna happen. ThenNewswatch. This magazine is my life and the lives of my colleagues. We intend to surprise Nigerians. From week to week, we shall show them that it will always bring new dimensions. So, we haven’t seen the last of it yet. There’s so much for one to say, to do.

Kevin: As a famous old man once said: “You ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Dele: Yes! You ain’t seen nothing yet

Kevin: Okay, a little more background about yourselves. You talked a boy being intellectually alive. What do you do to keep fit and good looking?

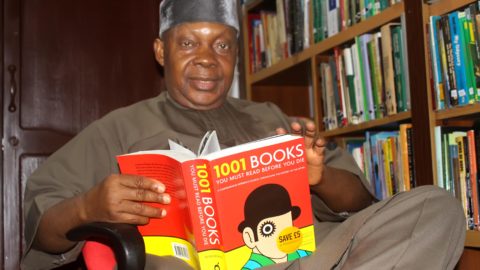

Dele: I play squash. I would like to swim but I am afraid of going under. Aha, I read a lot and I write a lot.

Kevin: You write a lot and play a lot?

Dele: I write a lot, I don’t rest. I don’t have time to rest. I wake up about 4 a.m. and work until 9 a.m. when I leave for the office. But I read, I play squash quite a bit; and I write.

Kevin: Talking about thinking, there was this time a few years back, when you were incarcerated, when you were held by the police. That must have been a lot of time for thinking. What kind of things did you think about? As briefly as possible, for instance, who were you thinking about—some of those who have been good to you, some of those who have played a role in your life and so on

Dele: No, I did not go into any deep sense of my pain when I was in jail. One thing you should not do in jail is to think. You should not take yourself seriously in jail. You must assume that you’re a joker and perpetually a laughing fellow. You might become the joker of the prison. I became the president of my cell, and it became my lot to make light the load of others there. I fought and saved one man from detention there. He developed high blood pressure, and I told the police, if that man was not taken to hospital, I was going to organize a rebellion in jail and they took him to the hospital. The Chief Fire Officer of the Federation was there, he lost a finger in the Nigerian External Telecommunication (NET) fire. The old man was from my village, I found out later. So I became his son and I tried to make light his burden. I had no time to think about anything serious because I knew if I should allow myself to fall into a recess, depression will overtake me. So, I refused to be serious. I didn’t even think about Mr. Adewusi, the Inspector-General of Police.

Kevin: That’s Dele Giwa for you, and I like to thank you, Dele, for coming to Just A Chat.

Dele: Thank you, Kevin.

Interview by Kevin Ejiofor on a Radio Nigeria 2 Programme, broadcast on Sunday, February 3, 1985

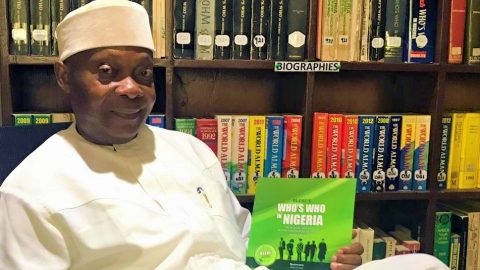

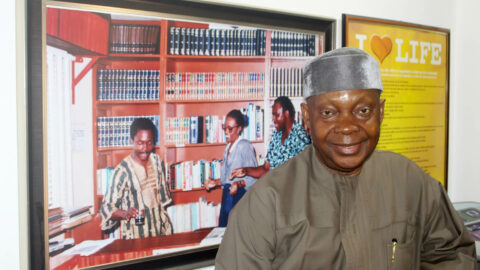

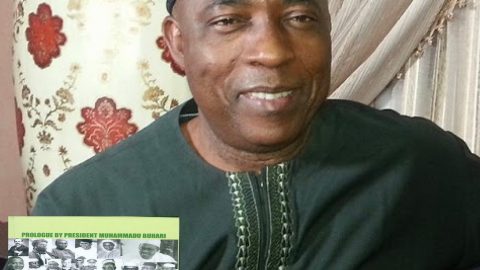

Extracted from the publication:

“PARALLAX SNAP: THE WRITINGS OF DELE GIWA”: compiled and edited by Nyaknnoabasi Osso and Nosa Igiebor, 2nd ed., 2017.