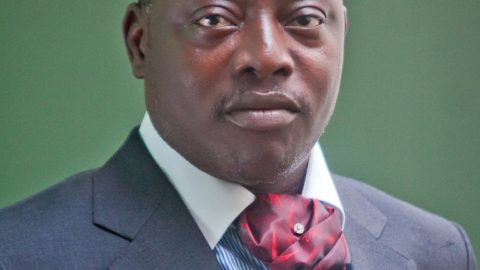

A Review by SAM AKPE

From Frustrations to Manifestations: The Metamorphosis of a Village Boy

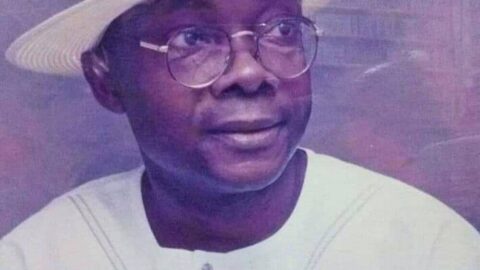

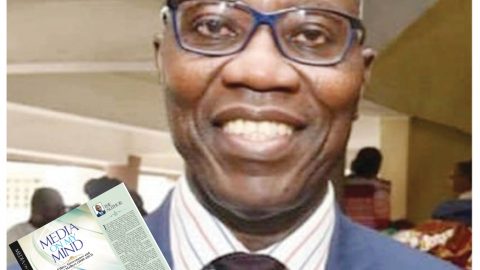

Several years ago, Yakubu Mohammed, former editor of the now rested National Concord, and one of the four original founders of the defunct Newswatch magazine, prophesied over Anietie Usen. After reading Usen’s blood-chilling report on the Liberian Civil War, Mohammed observed that though the reporter “is not a writer of thrillers in the mould of Irving Wallace, but he ought to be. Maybe, one day.”

Though it has been “a long time coming,” the tomorrow of yesterday may have finally arrived. Has the reporter become Irving Wallace? No! Not just yet! But while Mohammed prefigured that “he ought to be,” something tells me he is aiming higher. The proof can be seen in the sumptuous literary dish I have just finished munching; entitled: Village Boy — A True Life Story of a Tenacious African Orphan.

After reading Professor Joseph Ushie’s foreword to the book, I felt there would be no need for further review. Ushie is a specialist in general stylistics and literary criticism. He is a poet and a writer in the mould of Professor Niyi Osundare. Looking around, I have just spotted three volumes of his past works: Hill Songs, Eclipse in Rwanda and Popular Stand on my shelf as I write this.

Ushie’s conclusion, after thoroughly enjoying Village Boy, is that it is written “as facts of life, sandwiched, as it were, with native wisdom and the thrilling fiction that African folklores and fables are famous for.” He believes that the book is a combination of facts and fiction, “or what modern literature now recognises as faction.”

With just a little over 200 pages, Village Boy reminds every reader of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart or No Longer at Ease — a true story told with invented elements. It consists of 23 short chapters, written in concise paragraphs. The end of every chapter creates a natural, forceful desire in me to open the next page — compelled by the eagerness to know where the story leads.

The author — known simply as Anietie, by friends and colleagues — has mentored several outstanding journalists and administrators. I am a product of his push and kicks. He instilled in us the need to get the job done; professionally. I still remember him walking into the Pioneer newspaper production hall by midnight every Thursday, wearing that big-man smile, and asking: “gentlemen, just where are we?” Those were the days when journalism was not just about reporting the news. It included producing the newspaper. Anietie is journalism in motion.

Village Boy is written in typical Anietie’s style: brief, clear sentences and simple words—no complexity of expressions. He loves to paint pictures with words and leave the reader to see in colours. This is who he is. Each scene in the book is deliberately picturesque. You see as you read. Local expressions which are neither strict Ibibio nor clean Efik, are used to spice up conversations.

Without any contradiction, Village Boy is Anietie’s fictionalised autobiography. It is a story in the making, which hopefully, would be completed in another volume. The narrative is dramatic, inspirational and full of raw suspense. It is a fictional depiction of the author’s travails shortly after he lost his father and had only his grandmother and mother to look up to.

Village Boy is also, in many ways, an exhibition of the fate of every disadvantaged Nigerian child—especially those left in the seemingly secured custody of illiterate caretakers. It is an expository of discipline, hard work, and brazen-faced determination in the midst of hardship and extreme poverty.

Akan — the fragile but stubborn hero of the book — is a victim of failed hope. His father was an accountant, who worked in the neighbourhood of the rich and famous in Lagos. Tragedy however struck shortly after Akan was born. The father died in a car accident. His death marked the beginning of a life of struggle for his son.

The story opens with Nnenwa, Akan’s maternal grandmother, known better as Grandma—an example of industrious African women. Tough, determined and incontestably famous in the community, a lot of people knew and depended on her for different reasons. She was a midwife to pregnant women and herbal pharmacist to the whole community.

Village Boy is a well constructed recall that exposes the simplicity of rural life — a life without clocks and wristwatches; without pipe-borne water and electricity; a life where humans and nature meet in daily conference for mutual survival.

One day, Grandma woke up at an ungodly hour, and dared to step out of the house even after hitting her left toe against a stone — a superstitious signal that all was not well. Dragging a reluctant Akan along the dark slippery path to the stream, she got bitten by a dangerous “hungry snake.” It could have been a python.

As both fell and rolled, the water pots broke in pieces. Horror gripped Akan. He felt surrounded by a team of unholy ghosts. Even Grandma shouted in fear of death. After what looked like eternity, she got her senses back and dragged herself off the ground. She seemed more concerned about Akan than herself.

Eventually, both made it to the nearest house in sight. Grandma banged the door mercilessly. As she rolled out her identity to the fourth generation; the door opened. She had a name and fame that opened any door in the village.

Ironically, though Grandma went in search of medical help, she ended up prescribing the medication she needed. By his accounts, Anietie may inadvertently be advertising the superiority of herbs over modern day medicine. His description of snake leaf, including its unfailing medicinal value, and the efficacy of palm oil called mmanyanga — extracted from fried palm kernel — confirms this.

Life in the Village

Some chapters of this book will make you smile lavishly or laugh aloud. Just imagine the way some names are pronounced in the native language. Magdelene is pronounced Mmaginini. Or what do you think Samwere is? That is Samuel! Siiiiiisoooors is Anietie’s version of Jesus; while Jehovah is pronounced Sikofa!

Conveying pregnant women to the delivery home is done using the only ambulance available: the bicycle! The delivery process requires supernatural intervention. The midwife must bind and cast. When the baby finally comes, Grandma—the chief gynaecologist and midwife — leads in thanksgiving to God, and insults to husbands who only know how to impregnate their wives, with no knowledge of labour pains.

Grandma’s multi-purpose accommodation was a simple, dusty and constantly leaking mud house inhabited by rats, goats, fowls and Akan — whose bed was a straw mat spread on the floor. A victim of jigger-infested toes, Akan often found himself urinating in the bush in his dreams only to wake up on top of a wet mat. What happened? He had trouble with the rat that nibbled at his toes.

Village children enjoy life the natural way. Their crude creativity usually make up for lack of television and internet. Hunting for fat rats called ayod by digging into their chambers underground, is one of them. The book explains thoroughly how this is done — including the frustrations and accomplishments. Ever wonder why Nigerians — as economically undeveloped and socially traumatised as we are — were once declared the happiest people in the world? It’s all in the Village Boy!

The hunt for flying termites called ndube, and bull cricket called idiang is as much fun as it is a serious business. It is better experienced than described. From previous frustrations over failure to catch “rats for perppersoup” Akan triumphs in what Anietie calls “the barbecue of the poor.”

Another area of fun for the village boy is the folktale by Grandma. There is one entitled: the Vernacular of Lizards. It is a story of the arrogant rat and the humble and wise lizard. It is a depiction of social inequality usually created and imposed by one tribe over another; or maybe a case of George Orwells’ all animals are equal though some do claim to be more equal than others.

Bullies are everywhere. You find them in politics, business, cities, villages and even in families and animal kingdom. The good news is that for every noisy blustering fellow, there are also good natured people. While the reward for friendliness is good report—and more friendship, bullies always experience sour ends. The book recalls a story of a village bully that earned the curses of women and the punishments of angry elders.

Politics of the Village Boy

Viewed metaphorically, the story of Akan is the story of Nigeria. We started well as a country in 1960 with well churned out development plans. Then the military struck on the excuse that politicians were a bunch of corrupt tribal lords — indeed they were. Akan, just like Nigeria, was heading towards good life until a deadly calamity struck—his father died.

Destined to be a shining star, his father became the sun that rose with promises of a better day only to disappear suddenly under a thick cloud of despair. It was as though “the right hand of the village had been cut off and there was none to say restore.” Akan was the only surviving reminder of that short-lived glorious moment.

Akan was called BB—Big Boy. Was he? It is the same way Nigeria is labelled “Giant of Africa!” He was “a Big Boy in rags, with jigger-infested toes, chasing rats at day for meals and insects desperately at night for snacks.” But just as Nigeria is in Africa, despite its self-inflicted calamities, Akan grew up to be “the cynosure of all eyes,” his mother’s delight, “the center of her life and the heartbeat of his grandparents.”

Then, Akan went to school, dressed in over-sized clothes that were deliberately made to last him a lifetime. That was when the rebel in him surfaced. Finally he was in class—almost on his own terms. Despite the crippling poverty, Akan still had a sense of pride. We Nigerians also do!

One day, the class teacher asked a simple question, and picked Akan to answer. His response brought laughter and tears to the class. It went like this: “If you have N10 and your Daddy adds another N10 for you, how much money would you have?” Akan’s response was sharp and mischievous: “Aunty, my Daddy is dead.”

The insensitive teacher was not done yet. She repeated the question with amendment: “If you have N10 and your Uncle adds another N10 for you, how much money will you have?” Akan: “Aunty, I will have N10…. Aunty, you don’t know my Uncle. He cannot give me one kobo talk less of N10.” This attracted a prolonged laughter.

On rainy days, Akan covered himself with cocoyam leave to school. That was his umbrella. After school, he must crack palm kernel which was the mainstay of the village economy. They were used as money in exchange for tilapia fish and crayfish.

The Fun and Hard Lessons

Village Boy exposes the reader to a lot of things. The negative reward of deception is found in the story on the native doctor and the bonesetter. The story further exposes the unquestionable medical potency of herbs and tree barks. More interesting are the procedures adopted in their uses.

This book answers the question on the necessity for pet names. Every parent has a pet name for his or her child. Grandma had a basket full of them for Akan: My Hero, My Pride, My Gallant Boy, etc. Pet names inspire the bearer. They could make kids jump over walls to accomplish a task. Most pet names do not truly reflect who the bearer is. They are merely prophetic — a pointer to an aspiration.

Poverty, creativity, determination, bravado and punishment for small lies are well discussed in the book. What about religious promiscuity—or proliferation of churches based on ethnic or monetary rather than spiritual interests? Anietie captures this in its best brutal form. There is the unbelievable story of Atimoti (Timothy), the drunken preacher, who usually had his vagabond anointing through alcohol.

One day, Akan and Grandma took a ride in a lorry to the “concrete jungle” called Aba — the nearest township — to visit Akan’s aunty. Everyone among his peers knew that Akan was “flying” to Aba. While on the road, Akan saw all the trees running backward while the cloud move along with the lorry. When he saw a train in Aba, he almost fainted.

A discourse on what trade Akan should learn, in place of going to secondary school, is quite interesting. Would it be bicycle repairs or photography? Before I forget, Anietie’s reflection on a day with the photographer is beyond any adjective. From there, he moves to village sports. Did you ever live in the village? It’s time to identify your favourite sport.

Forced into slavery as a houseboy, the proud Akan refused to hang in there. He ran back to Grandma. He was determined to have a formal education. But how possible would that be? Akan’s mother took over at this point. She wanted her son in school and nothing would stop her. She reached out to her late husband’s friends. Before long, Akan secured a scholarship. The good seed sown by his late father was yielding bountiful fruits.

At long last, Akan took off to secondary school. From the first day, he made up his mind to become a prefect. He did! He joined others to the stream every morning. Then his mother suddenly got a job in Calabar. That was where he went every holiday. He sold kerosene at night and hawked bread at daytime to raise the needed school fees.

Life in Calabar

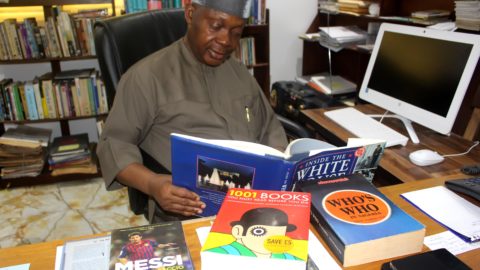

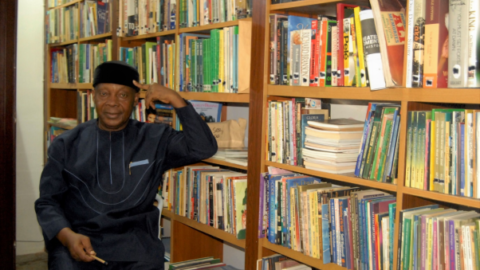

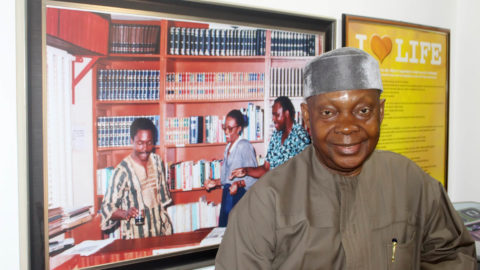

Then one day, he discovered a library in Calabar. That changed his intellectual fortune. The sight of books thrilled him to no end. He started reading whatever he could lay his hands on: local newspapers, international magazines, history books, biographies, politics, just books upon books, including James Hadley Chase. He was sowing seeds. He fell in love with words. He also had a nick name: Emperor—he ruled his world of knowledge.

On completion of his school certificate examination, Akan studied political science at the university, did his national service in Kano and emerged the best corps member. He was already in love with journalism. His first article in the Nigerian Chronicle fetched him a princely N12.

Anietie at this point seemed to be in a hurry to end the attention-gripping book. No detail information is given about Akan’s stay in the university. How did he fund his education at that level? What were his grades? What about his social life? How did his village mates and wicked uncle react to this emerging city boy?

Ever heard of anti-climax? I have too — though I am not well versed in the dramatic arts. Anietie simply shut down discussion when I was getting ready for more. He leaves a lot of questions unanswered. My conclusion is that he did not want to get too close to reality. Akan would have been unmasked if discussions had gone beyond this point.

All the same, this is a story well told by — the real Village Boy. Stunning descriptions leave you in breathless anticipation of what would happen to Akan or Grandma next. Every chapter has matching illustrations. Every illustration is loaded with interpretations. None leaves the reader with a vague feeling. What a tale!

The book suffers minor setbacks in just one aspect: proofreading. There are avoidable typos. You will likely see robber balls instead of rubber balls; sunset instead of sunrise; him instead of his; among others. No fault of the author; no minus on the impact of the contents.

Keep Holding On!

Never give up! That’s the lesson in all of these. It is the central theme of the book. This is exemplified in three characters namely Akan, Grandma and Maama. They refused to settle for anything below excellence, because they saw the end from the beginning.

Akan, though frustrated by the death of his father, was strengthened by Grandma’s unwavering care. Beaten repeatedly by his uncle, bullied by playmates, shamed by repeated failures, and bruised by hardship, he endured; with his vision unshaken.

The conclusion is that Nigeria can rise again.

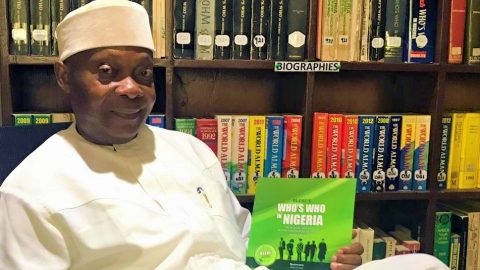

SAM AKPE …is our CONSULTING REVIEW EDITOR.