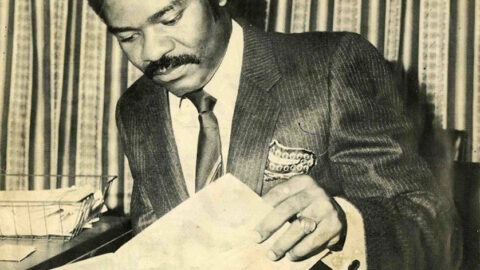

On July 7, 1998, they brought Chief Moshood Abiola home in a body bag. That was not what we expected, but that was what we got. The ‘they’ was the military junta led by General Abdulsalami Abubakar. Abubakar had become head of the junta following the sudden death of his boss, General Sani Abacha, on June 7, 1998.

Excited Nigerians, rejoicing at the sudden death of the tyrant, had dubbed the event miracle ‘98. Abubakar, a suave and morose military officer, went ahead to brighten the political space, but then inexplicably delayed in freeing Abiola, the winner of the June 12, 1993 presidential election, who had become Abacha’s most famous prisoner.

Also detained like Abiola were scores of political and military leaders including General Olusegun Obasanjo, the soldier who ended 13 years of military rule when he handed over power to elected President Shehu Shagari in 1979, and Beko Ransome-Kuti, the (late) physician chairman of Campaign for Democracy, CD. Obasanjo’s erstwhile deputy, General Shehu Musa Yar’Adua, had also died in Abacha’s prison.

Abubakar freed many of our leaders and colleagues who were in the gulag including the likes of (Late) Chief Bola Ige, first elected governor of old Oyo State, Alhaji Lam Adesina, who was destined to become the next elected governor of Oyo State, Dr Ransome-Kuti, Mrs Chris Anyanwu, the publisher of TSM magazine, George Mba of TELL, Ben Charles-Obi, Kunle Ajibade of the TheNews and many others, but not the great man, Moshood Abiola.

We called a meeting of the Idile Oodua, the leading underground group during the fight against Abacha, at Onyx Plaza, Ikeja, to deliberate on developments. We were all enthusiastic that Abiola would soon be released and then we would insist on an immediate exit of the military. We resolved that Abubakar must be compelled to hand over power to the president-presumptive. We expected Abiola to form an all-inclusive national government. We were in high spirit.

“What if Abiola too should die like Abacha?”

The question had been posed by Prince Paschal Adeleke Idowu, a man of steel built in elegant form. He was a management staff of Royal Exchange Assurance Plc and one the most steadfast and bravest patriots of The Resistance. Heavy silence fell on our meeting. This was followed by an animated debate. Our conclusion: Abiola cannot die in detention. Our country, our people and history were waiting for him.

The following week, we held a meeting in the Ibadan home of Chief Bola Ige, the deputy leader of Afenifere, who had just returned triumphantly from Makurdi Prisons, Benue State. Ige was the chairman of Alpha, where I served as the secretary. It was composed mostly of leaders and representatives of different groups. One of the leaders of that group, Dr Wahab Dosumu, Second Republic Minister of Housing and member of the Senate between 1999 and 2003, died, bringing home to us why the story of that dark era needs to be told. Dosumu was one of our outstanding leaders and he attended that important meeting in Ige’s house in 1998.

‘What if Abiola dies’

Ige explained to us that Abubakar appeared to be an Omoluabi who may be willing to distance himself from the evil ways of his predecessor. He said the leadership of Afenifere, the pan-Yoruba political and cultural movement, was in constant touch with the new junta. He spoke glowingly of its pointsman, Major-General Leo Ajiborisa, first military governor of Osun State. He was sure Abiola would be released “within days!”

“What if Abiola dies?” we gingerly posed the Paschal Question? There was again an animated debate. The meeting’s conclusion: Abiola dare not die in detention!

Few days later, they brought Abiola home from Abuja in a body bag.

Senator Abraham Adesanya, the leader of Afenifere, was inconsolable after the death of Abiola. “Where did we go wrong?” He would ask again and again. “We must have made errors!” He would end his lamentation with his famous prayer: Ki Olorun ma k’odi aimose siwa (May God not turn our efforts into errors). Could the June 12 story have ended in a different way with Abiola coming home in triumph?

Some of the old men who led the battle for June 12 are still with us. They have fought their battles, the war has ended (has it ended indeed?), but they have not won the war. The war was fought so that Yoruba land can make certain demands on the Nigerian commonwealth and that Nigeria can become what our leaders termed “a proper federation.” Some of these demands are being met. Most remain unmet because there is no elite consensus to even articulate these demands and create a coherent strategy to pursue and attain them.

‘C-in-C in captivity’

The June 12 war was waged while the Commander-in-Chief was in captivity. I have often wondered if events could have taken a different course if Abiola had, from the onset, refused to cooperate with Abacha. How would history have responded if the great man had been opened to a different kind of advice instead of the one that led him into a fatal embrace of the Abacha dictatorship in its nascent days? But we know, a leader is really a prisoner of his advisers, his inner court, the ministers, the paladins, the jesters and the palace guards. It is for him to rise above them and distil from the cacophony the ultimate melody that would lead him to the embrace of destiny and of greatness.

The Turning Point

The turning point for us was the November night in 1993 when Abiola visited Abacha in Lagos. We saw the footage on national television. It sent a confusing signal and we did not really know how to respond. After that meeting, some of Abiola’s top men including the vice-president elect, Babagana Kingibe, and Alhaji Lateef Jakande, the former Action Governor of Lagos State, were appointed ministers. Some months later, I met a sober Abiola in his Ikeja home. On the way to his first-floor sitting room were still the large pictures of Abiola and his “friends” like Babangida and Abacha. He was getting discouraging signals from the Abacha camp. The new military ruler did not appoint civilian deputy-governors for states as he had earlier promised. Kingibe, the vice-president-presumptive, was now enjoying his new pedestal as the Minister of Internal Affairs. Abiola was thoroughly disappointed, but, nonetheless, in a defiant mood. It was to be our last meeting.

While Abiola was in detention, the June 12 struggle was led by the last brigade of the Awoist vanguard, those intrepid warriors who dedicated their lives to the ideals of freedom and justice: Chief Michael Adekunle Ajasin, Senator Adesanya, Chief Alfred Rewane, Chief Anthony Enahoro, Chief Bola Ige, Senator Jonathan Odebiyi, Archdeacon Emmanuel Alayande, Dr N.F. Aina, Otunba Solanke Onasanya, Alhaji Ganiyu Dawodu, Senator Cornelius Adebayo, Chief Ayo Adebanjo, Chief Olu Falae, Senator Ayo Fasanmi, Chief Ayo Opadokun and many others. They were hardy men, tested by fire, forged in the furnace of adversity, unblinking in their stare at danger and unshakable in their faith about the rightness of their cause. They believed that the spirit of Awolowo was still guiding them and they would want to confirm that by what they called the Awo Credo. Let me give only three illustrations.

In 1994, I had gone to the Ikeja GRA home of Pa Alfred Rewane in the company of Funminiyi Afuye. Rewane was an ebullient old man, full of humour and good grace. A very successful and wealthy businessman, he had served as Awolowo private secretary during the golden era of the 1950s. Each time he mentioned Awo’s name, he would always remove his cap as a sign of respect!

The Idile meeting

Sometimes in 1997, I had led my colleagues in the Idile to hold a meeting with the conclave of Afenifere leadership. The Idile delegation included Bayo Adenekan, Afuye, Oba Adedokun Abolarin (now our royal father, the Orangun of Oke-Ila in Osun State), Dayo Adeyeye, Biodun Bankefa (now known as Pastor Biodun Bamdupe), Kayode Anwo and Paschal Idowu. Most of the leaders of Afenifere were present. We were in the midst of a heated discussion when silence suddenly fell on the group. It was 3 p.m. Sir Olanihun Ajayi explained to us: “Our leader has instructed us that we must always pray for Nigeria and Yoruba land at 3 p.m daily wherever we are.” Ganiyu Dawudu was then asked to pray.

Late 1998, it was clear that Chief Ige was eyeing the Presidency. The Metropolitan Club, Lagos, had invited him to come and deliver a speech which we expected would signify his intention to the public. The death of Abiola had cleared the road to that possibility. Originally, Ige had said if Chief Enahoro, the leader of the opposition National Democratic Coalition, NADECO, was interested in the Presidency, then he would not run (“Nobody understands Nigeria better than Tony,” said Ige.) Indeed, Ige had asked Professor Wole Soyinka to sound out Enahoro on this. Enahoro had declined, insisting that Nigerians needed to agree on a post-military era Constitution first before we decide on who will be President. With the coast almost clear for him, some of us; his younger friends; felt Ige should open a campaign office.

Bola Ige and the Afenifere decision

“Our leader would not like that,” he said. That was more than 11 years after the death of Awolowo. Ige said he needed to wait for the decision of Afenifere.

Those were the era of believers. We now have politics without belief and religion without godliness.

There is a lot of tactical movements in Yorubaland, especially among leaders of the two main political parties, the Peoples Democratic Party, PDP, and the Action Congress of Nigeria, ACN (or its newly adopted name, All Progressive Congress, APC). It is disturbing that Yoruba political leaders are behaving as if Yorubaland is an island unto itself, unrelated to the larger political alchemy of the larger Nigerian state. We only need to reflect on contemporary Nigerian history to know that this trend of parallel operations among our leaders have always worked against our people. Chief Enahoro, in a moment of reflective frustration, had declared: “the Yoruba, in politics as well as in religion, prefer to worship many gods.”

Yet at this point again, we are confronted with the Pascal Question. Though our leaders may differ in tactical approach to national politics, there is the need to have a set of unanimous strategic objectives. As events unfold, we need to think of options that would serve the best interest of Nigeria and the Yoruba people. Like during The Resistance, I am convinced if our leaders have been prepared for the Paschal Question, the situation may have been different. Then we were not prepared to think of the dark twist of history. It is this lack of strategic thinking that has plagued Yoruba politics and it is again casting a negative influence on national affairs.

Tactical blunder

In 2011, the PDP had zoned the Speakership of the House of Representatives to the South-West. The party had zeroed in on Honourable Mulikat Akande Adeola from Oyo State to get the job. However, a rebel faction of the PDP defied the party leadership and elected Waziri Aminu Tambuwal instead. They got this done with the critical support of the representatives of the South-West in the House of Representatives who are mostly members of the ACN. It is not clear what strategic objective or goals those leaders of the ACN wanted to achieve by ensuring that the leadership of the National Assembly comes from only the northern part of Nigeria, while Yorubaland is left high and dry. What was the purpose of this tactical blunder: freedom or slavery? Good or evil? Think of cutting your nose to spite your face!

HYPOCRISY

In 2013, the June 12 anniversary was celebrated with fan-fare in many state capitals of the South-West. Even to underscore the importance of that day, Labaran Maku, the then Minister of Information, joined us in Lagos to pay tribute to Abiola.

If Abiola was this important to our democracy that we continue to mark the anniversary of his voided victory, why was there so much outcry when President Goodluck Ebele Jonathan decided to honour him with the re-naming of the University of Lagos? If the truth must be told, the June 12 celebration had a tinge of hypocrisy to it.

How many books and documentaries have been commissioned on the life of the great man by those who claimed to love Abiola? (We thank God for Wale Osun, whose “JUNE 12: CLAPPING WITH ONE HAND” provides a brilliant insight).

How many of those who have been propelled to power by Abiola’s heroic sacrifice have bothered about his immediate and extended (and extensive) family? Where are the thousands of men and women who enjoyed Abiola’s scholarships to further and complete their education?

Where are the members of the army of supplicants and beneficiaries who daily throng Abiola’s Ikeja palace? How many of these men and women who benefitted so much from Abiola’s expansive munificence have bothered to find out how the wives and children are coping since the passage of the man in 1998? The truth is that our collective memory is poor and our sense of history is worse.

There is a chilling reality that the Nigerian people, especially the youths, do not fully appreciate the enormity of Abiola’s sacrifice and the centrality of that sacrifice to the current democratic dispensation.

DIFFERENT ROUTE

Had Abiola taken a different route and not plunge into politics, may be the history of our great country may have been different. Most likely he would have built his own university and, if he likes, named it after himself.

I hope those men and women of power who profess to love Abiola would follow the example of President Jonathan and take time to remember his profound sacrifice and the debilitating impact of this sacrifice on his immediate family. As we remember Abiola, we should also not forget why he died.

One great tribute we could pay him is for the true leaders of our people never to be caught off-guard again so that they can understand the imperative of elite consensus in reaching for and achieving collective strategic goals. This elite consensus is “necessary to preserve the legacy of democracy and justice that Abiola died for. Remember the Paschal Question”!

Perhaps Abiola could not escape the heavy hand of fate because he was too trusting, too human and too loving to understand the deep guile of a desperate and complicated man like Abacha. He fell, not because he was weak or greedy or afraid, but because he was human in the full ecclesiastical meaning of the word. It is this deep humanity that confirms his greatness.

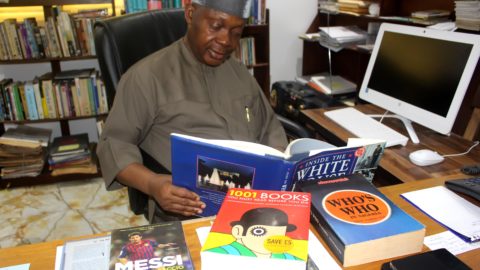

* Dare Babarinsa, a veteran Journalist and a dedicated friend of Biographical Legacy and Research Foundation (BLERF), a renowned Columnist with the Guardian Newspaper, Nigeria and Co-founder of TELL Magazine wrote this article for VANGUARD Newspaper in July 2013 in memory of Chief MKO Abiola, GCFR, an Icon of Democracy in Nigeria.

“At Biographical Legacy and Research Foundation (BLERF), We celebrate Outstanding Personalities, dead or alive”. – Nyaknno Osso, Editor-in-Chief (BLERF)

Daddy u are doing great work more grace sir