BY AKIN MABOGUNJE

Obasanjo’s avid love of learning, acquiring knowledge and doing new things deriving from that knowledge is evident throughout the different stages of his life.

The decision to honour the declaration and the actual handing over power from military rule to a civilian administration in Nigeria on 1st October, 1979 was a defining moment in the life progression of the man, Olusegun Obasanjo. It highlighted significant traits in his character and was to shape his image within the international community.

He was certainly the first military Head of State to voluntarily hand over power to an elected civilian president if not in most of the developing world but certainly in Africa. It underscored his being a man of honour, of considerable integrity, a true officer and gentleman; a man whose word is his bond and a person with whom the world can readily do business.

I first set my eyes on the man, Olusegun Obasanjo, sometime in 1977 when, as the head of the military Head of State, he came to the newly defined Federal Capital Territory to see what we were doing in respect of the ecological survey and the census of the economic assets and inhabitants to be displaced from the area. I had, of course, heard of him as the military commander that brought the Nigerian civil war to an end.

I also knew that he was the Chief of Staff, Supreme Headquarters, who was persuaded to take over as Head of State and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces on the assassination in February, 1976 of his predecessor in that office, General Murtala Mohammed. But it was not until after he left office in 1979 that we became increasingly close for me to be able to have some insight into the complex and often enigmatic personality known as Olusegun Obasanjo.

Even then, it is my considered view that is virtually impossible for anyone to claim he can be definitive enough as to his knowledge of another human being, however close their relationship. Yet, to extent that one observes some consistency in character traits, one can essay some opinion as to what makes a particular individual tick.

THE EARLY INFLUENCES ON OLUSEGUN OBASANJO

Three influences from his early life would seem to me to define much in the character of the man, Olusegun obasanjo. The first is the love of hearth and land; the second is a strong religious conviction and trust in God; and the third is an avid love of learning, acquiring knowledge and doing new things deriving from that knowledge. Olusegun Obasanjo was born on March 5,1937 in Ibogun OLAOGUN, one of some 30-odd villages bearing the name “Ibogun’’ in an extensive tract of land north of the small town of Ifo in Ogun State. I know little of Obasanjo’s parentage other than the fact that they belong to the Owu sub-tribe of the Yoruba.

The Owu are a subgroup of the Yoruba whose history has been pivotal to much of what happened in this part of Nigeria in the 19th century. Along with a historian colleague, Professor John Omer-Cooper, I had the privilege of writing about the Owu people in a publication of the University of Ibadan Press in 1971.The heartland of the Owu Kingdom in history was in an area north of Ibadan. Owu town, however, was destroyed around 1821 and a sizeable part of the displaced population moved to join the Egba in their new settlement of Abeokuta, sometime after 1830. From here, many Owu people moved towards southwestward from Abeokuta to establish numerous rural settlements including the Ibogun group of villages.

Although regarded as part of Awori land, this area was a scantily populated and insecure border region requiring people of considerable courage and determination to establish settlements there at the time. The Owu have always had the reputation among the Yoruba of being a courageous and stubborn people, a trait which must have passed down through the generations and of which the man, Olusegun Obasanjo, show ample evidence.

Obasanjo’s love of hearth and land is particularly evident in the continued strong attachment to his birthplace. Apart from building himself a modern house in the village which he visits frequently, he is always proud to take his friend to the village, showing them the primary school he attended and relating easily with his kinsmen even after he had risen to be the Head of State of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

His love of dancing to native airs with his people is also one of the manifestations of this ease of relating to the common man anywhere and everywhere. It is seen, for instance, in his later years when he leads his political party on election campaigns. He went on to establish an experimental primary health care system for the villagers, offering them both conventional modern and traditional alternate clinic to deal with their ailments.

When the Ogun State Government under Chief Bisi Onabanjo decided to locate a campus of the Ogun State University Ibogun, Obasanjo was greatly enthused and wished that the campus could be made a focal point for planning the merging of all the Ibogun villages to form a single town. He was willing to rally all Owu sons and daughters in Egbaland to support the development of this campus, a development which halted with Buhari military coup of 1983.

Since then, however, Obasanjo, with others, has succeeded in fostering a new sense of Owu consciousness among his kinsmen not only in Egbaland but everywhere they had settled in Yoruba and since the dispersal of their home town in 1821. Today, he has collaborated in instituting an annual Owu day celebration for promoting solidarity amongst them and is very proud of his chieftaincy title of Balogun (Commander-in-Chief) of the Owu of Abeokuta.

It is also to this strong love of hearth and land in the rural setting of Ibogun that we must attribute Obasanjo’s ardent and passionate love for farming and agriculture. And, to my mind, it is to this same attribute that we must appreciate his strong patriotic fervor, his love for and commitment to Nigeria, his fatherland, which his years in the military must have helped to greatly consolidate.

His strong religious conviction and trust in God is evident to anyone close to his household. I had no such experience of him during his years as a military head of state but by the time he returned as civilian president, the day began for him with family devotion involving all members of his household and other close colleagues who cared to join in. As President, he had the advantage of the state house chaplain to preside on these occasions. I have no idea how much of this abiding faith is due to Baptist Christian Missionary influence in his schooling years at the Baptist Boys High School in Abeokuta.

There is, however, no doubt that his commitment to a temperance posture where alcoholic drinks are concerned and even his use of word “Temperance” in naming some of the private institutions established by him derive from this source. Obasanjo’s redoubtable courage and fearlessness can also be ascribed to this strong religious conviction. It certainly underscores his brilliant achievements as a military commander, especially in the decisive manner in which he brought the Biafran war to a close. It is also evident in his outspokenness on national issues in the current democratic dispensation.

Obasanjo believes in divine interventions in critical periods of his life. His escape from the fatal injection planned for him under Abacha’s regime and his second coming as the civilian head of state of the Nigerian Federation he puts down to God’s intervention in his life. It has also been claimed that his difficulty in dealing peremptorily with the proponents of “The Third Term Saga’’ during his presidency was because he wondered whether this was another instance of divine promotion.

Obasanjo’s avid love of learning, acquiring knowledge and doing new things deriving from that knowledge is evident throughout the different stage of his life. He did not go to school until he was nine years of age. The story is told of his being on the farm with his father when the latter, out of the blues, stopped and asked his dutiful and hardworking farmer-son: “This school thing, can’t you also go?” Apparently surprised, he assured his father that he could if his old man so desired.

His avid love of learning soon began manifesting at the primary school in Ibogun and later at the Baptist Boys’ High School in Abeokuta. Even when he joined the army in 1958, this love was only starting to blossom. Indeed, at the Defense Service Staff College in Wellington, India, the commandant’s confidential report of the 20th Staff Course in 1965, noted that he was “the best officer who was sent up till then from that country (Nigeria) to Wellington.’’

Nonetheless, it was after his military career that this capacity of his had free rein. When he chose to retire into farming, he decided to go for short-term training at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). To help promote the idea of learning as a life-long obligation, he registered as a student in the National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN) when he was still the nation’s president. On his own, he continues to spend time learning and innovating over a wide range of issues.

It is, of course, presumptuous to single out only three influences in the life of any individual. There can be no doubt that for a person of such forceful and versatile personality, other influences can be identified especially as he grew up and operated in different theatres of life such as the military, the political, the social and the economic. There is little doubt, however, that in all these areas, something from these three influences of his early childhood would be found to underpin the manner of his operations.

Since he was such a towering national figure on becoming military head of state and a two-term civilian president, it will be useful to see how these influences affected his dispositions in these various contexts. I have, therefore, chosen to look more closely at his personality in these different situations. I have divided the rest of this paper into four parts.

The first examines the man – Obasanjo – when occupying the highest seat of power in the country; the second looks at him when he was out of power whilst the third attempts to capture something of the image he has created for himself internationally. The fourth part then considers the nature of his legacy the man –Obasanjo- is likely to leave for the coming generations of Nigerians. A concluding section evaluates the controversial nature of his impact on the Nigerian nation and society.

The Man—Obasanjo in Power

In his first attempt at providing some explanation of his intervention in the power politics of the country titled: Not My Will, written in 1981, Obasanjo tries to indicate how his ascension to power was not a matter of personal ambition but of divine promotion. Once he found himself in that position, however, he threw himself fully into making the decisive impact on national life which the situation demanded.

The history of his progression from being Chief of Staff Supreme Headquarters to General Murtala Mohammed and his becoming the Head of State on the assassination of the latter is captured very well in that publication. What is interesting to me and relevant to our present purpose is the light the whole process casts on the nature of his personality. Whatever one thinks of the Nigerian Army, it has evolved as a veritable microcosm of what the Nigerian nation should become—a melting pot of many ethnic groups living together in mutual respect and providing opportunities for individuals to prove their mettle especially in leadership positions. Obasanjo seemed to have flourished in such a milieu.

His competence, decisiveness and leadership qualities were already manifest in the manner in which he moved as Commander of the Third Marine Commando to bring an end to Nigerian Civil War. These qualities were to make him one of the reference figures that junior colleagues considered when they decided to terminate the first military regime under General Yakubu Gowon. He, of course, did not participate in that coup d’etat. Those who did knew Obasanjo was one of their senior officers who could help redeem the situation that had provoked them to this extreme measure.

I had very little contact with Obasanjo as a military Head of State. From the ringside, however, what was evident was that General Murtala Mohammed and later General Shehu Yar’adua, he tried to make Nigeria operate as a united, strong and intentionally purposeful nation. His love for his country was evident in all of the decisions taken at the time.

Even though with hindsight it is possible to see that his colleagues did not fully appreciate the implications of the multi-ethnic nature of the Nigerian nation or how truly and effectively to manage such complexity, he tried to forge a high degree of unity and uniformity into the administration of the country. What was impressive, however, was that they tried to be innovative in many decisions they took. The Local Government Reform and the Land Use Decree testify to this trait.

In all these, Obasanjo’s decisiveness in policy matters continued in the military tradition of insisting that conclusions be implemented “with immediate effect”. It must be admitted, though, that these conclusions occur after due consultation with the relatively narrow “Kitchen-cabinet” of civil servants and military colleagues in the Supreme Military Council.

The general approach to national issues at the time, especially in the social and economic realm was what can be referred to as “statist’’. This approach is best reflected in the words of the Second National Development Plan (1970-74) which expects that “the State must control all the commanding heights of the nation’s economy’’. This meant that both at Federal and State levels, government became the major proprietor or operator.

Whether it is in air, marine, or rail transportation, the development of the nation’s Iron and Steel and Petroleum Industry, in the ownership of Schools, Universities or Health Institutions, Sport stadia and so on, the role of government as owner and operator was paramount. Of course, this posture was possible partly because of the heavy windfall from the export of petroleum and partly from the apparently successful template presented by the Soviet Union and other Socialist countries at the time.

Twenty years later, when he returned as civilian president, so much had changed that Obasanjo too had to change his views and strategy. Most of the areas of social and economic life in which government had intervened so heavily had to rise up to the challenges of growth and development. Indeed, everywhere the failure of states enterprises has dragged down the development thrust of the country and enthroned huge infrastructure deficit, debilitating corruption and pervasive poverty in the land.

The Nigerian Airways had lost most of the 27 aircraft in its fleet and was being harassed all over the world for indebtedness. The shipping line had lost of most of its vessels and the last was about to be sold off cheaply to a local bidder. The dual carriage ways constructed to ease the heavy, port-oriented traffic from Lagos northwards to Ibadan and eastward to Benin had gone into serious state of disrepair whilst the railway system had become truly comatose.

The situation in the educational and health sector was no better. The Universities, most of which were now owned by the Federal government, had fallen sharply from their international rating. Government hospitals including the teaching hospitals of universities had come to be “mere consulting clinics’’. Most of them had lost their highly skilled staffs to other countries, especially Saudi Arabia and the United States.

Obasanjo, as a very pragmatic and insightful leader, had to critically reappraise the situation. He appreciated that the country, with its federal character syndrome and indifference to meritocracy in appointment to important management positions, was certainly not ready for a “statist” approach to development. The private sector with the inevitable market sanctions for poor management had to be enthroned to drive large sections of the nation’s social and economic life.

This turn-around, he immediately set out to initiate on his return as a civilian president. The jury, of course, is still out in terms of evaluating his achievements in providing the appropriate socio-economic framework and the right enabling environment for the private sector to flourish and develop, especially in the critical areas of infrastructural deficits. Years of public sector dilatoriness and incompetence had helped to breed a high level corruption in getting anything done in the country.

Much of public resources especially in the oil sector, had come to be allocated to eminent individuals. It was thus not surprising that the first bill that Obasanjo sent to the National Assembly on the occasion of his second coming was on how to deal with corruption. He did not appreciate how much his own principled position on corruption was at variance with many in the National Assembly. It took nearly two years before a watered down version of the bill he sent to the Assembly could be passed into law.

This difference in posture as to the urgency of dealing with corruption in the land was to undermine to a large extent the relationship between the Presidency and the National Assembly particularly during the first term of Obasanjo in office. The decision to deal with corrupt individuals more via the police route of the EFCC (Economic and Financial Crimes Commission) under the chairmanship of Mallam Nuhu Ribadu rather than the judicial route of the ICPC (Independent Corrupt Practices and other related Offenses Commission) under the chairmanship of Honourable Justice Mustapha Akanbi and later Honourable Justice Tunde Ayoola did a lot to reduce the feeling of impunity and complacency on issues of corruption in the country.

Of course, there were grumblings, especially in the media, that the EFCC was selective in its operations, dealing allegedly only with those unbeloved of the presidency. Whether true or not, the determined manner the agency went after those whose corrupt practices came to its notice sent a strong message to everyone in the country and helped to raise the expectation that corruption in the country could be contained. Since the end of the Obasanjo’s presidency, the more relaxed posture of the succeeding presidents based on observing “the rule of law” has led to a backsliding in the struggle and strongly indicates that corruption is not something to be fought with kid gloves.

The same expeditiousness characterised his approach to decision-taking this time around. When an issue was brought for consideration to Obasanjo or when he presided over a deliberation, once he had listened to both sides and a decision had been arrived at, one could expect action on the matter within hours or a matter of days. Obasanjo used the telephone as a veritable and critical tool of decision making.

Any of his ministers could expect to be called on the telephone at any time of the day or night to shed light on his or her part in a decision making process. Of course, many of his personal friends had to demure when he extended this style of calling them up at some unholy hours of the night to find out some facts from them. Nonetheless, this promptitude in decision-taking made government under Obasanjo so much more dynamic, diligent and result oriented.

Someone once described Obasanjo as basically a “strategist”. Given his military background this was easy to understand. But this description was based on Obasanjo’s approach to many issues, including even his interpersonal relationships. This underscored the fact that he was often concerned with immediate political or personal gains of a tactician but rather wished to send out a message of what acceptable to him and should be to the relationship on the long term.

This has often meant that he wanted his friends, acquaintances and kinsmen not to assume that he would bend the rule in their favour or indulge them to flout regulations simply because he had the power to do so. This gave the impression of a hard-hearted, inconsiderate and unfeeling person. Especially during his first coming as a military ruler and a young man at that, it helped to set the limits to which friends and acquaintances could take him for granted.

This principled position extended to even members of his own nuclear family. It has left some of his children feeling over disciplined and estranged even though it is clear that he truly loves them. It has also fuelled the accusation that Obasanjo did not care for his own ethnic stock when in power. Yet, those whom he had helped on his own terms (and they are very many) regard him most benevolently.

This same strategic element in his character made his second coming as president most interesting. Someone once remarked that when you went to the State House in Abuja under President Obasanjo, you felt you were a Nigerian because virtually all the major ethnic groups were represented among the staff you were likely to meet there. You did not feel overwhelmed by the ethnic affiliates who may burst into long discussions in their local tongues ignoring that others were around who did not understand what was being said.

It was a measure of his self-confidence that he did not feel the need to surround himself as president only with his own kinsmen. This also made acceptable all over the country and greatly widened his circle of friends. On the other hand, it made it such that the biblical adage is correct in Obasanjo’s case that “a prophet is not without honour, save in his country, and among his own kin, and in his own house”. Thus, in the election to Civilian Presidency in 1999, Obasanjo hardly won a majority of votes in the Yoruba Area of the country.

His self-confidence did not go down too well with the media, especially those based in the Lagos-Ibadan axis. They thought the president appeared to “know-all” who did not care for other people’s ideas. Consequently, it became the practice to report most policies of government not so much to promote or support them but largely to find their weak points or omissions. This, of course, was not an unexpected role for the media to play in the affairs of the country but a number of them took on positions that gave the impression not simply of being justifiably critical but almost downright adversarial.

Yet, some of those policies came to start the process of cleaning the deep rot into which the country had fallen in the twenty years since Obasanjo left office. His champion of privatization of most of the derelict and often obsolete investment which he started in his first coming such as the Ajaokuta Iron and Steel Complex was seen as “selling off the nation’s patrimony for a pittance”. His attempt at privatizing the numerous failed government-owned enterprises was also dismissed as feathering the nest of cronies.

His frequent overseas travelling to push for “debt-forgiveness” from members of both the London and Paris Club of creditors so as to release more resources for developments was dismissed simply as “a love of junketing round the world”. Nonetheless, his vigorous promotion of private sector leadership and partnership in various areas of the economy such as telecommunications, housing, infrastructural development, education especially at the tertiary level and health services are starting to be accepted as the only way to go for the country to move forward. His decision to establish a contributory pension scheme where a large pool of long-term savings can be accumulated for promoting infrastructural, housing and other capital projects is also gradually being appreciated in the country.

Obasanjo—Out of Power

It is, however, when Obasanjo was out of power that his inner strength and humanity as well as his fervent dedication to the Nigerian project became most evident. For most Nigerians, the idea of former Head of State leaving office to take up the lowly profession of a real farmer, not an absentee farming proprietor, was an interesting rarity. I confess that I was quite intrigued by this decision of his. For this reason, I was interested to see how he was adjusting to the situation when I led members of the Governing Council of the newly established Ogun State University to see him on his farm in Ota in 1983.

We found him dressed in the loose sokoto and dansiki of a peasant farmer. Indeed, we found that he prided himself so much with being at one with peasant farmers that he had a statue of himself made at the entrance to the farm dressed characteristically as a peasant farmer with a hoe on his shoulder. He did not go for the prestigious mode of working with tractor although he was trying out various types of tractors on the farm to see which was best for the local soil. His farm grew corn and had large poultry and piggery sections. He was also developing a rabbitry and snailery unit and nurturing a small aqua culture on the farm.

Having borrowed the capital for establishing the farm, he was more like the farm manager than just the proprietor. I was amused to learn of the many ways he had tried to protect the farm from thievery and larceny among his staff. I thought his idea of fencing a 200-acre farm was unrealistic until he told me that the cost of the fencing was less than what he would have lost if he had left the farm unfenced and miscreants had robbed him of his piggery alone.

It was also most interesting seeing him sit at closing time on the Statue-ledge at the entrance to the farm to keep an eagle eye on petty thievery of poultry products by both male and female staff members of the farm. Over time, a true espirit de corps seemed to have developed among the staff. It was fascinating to watch how this had been extended to include him. Since Obasanjo enjoys dancing to local music and native airs, it was always interesting to see him joining in dancing with his staff during any occasion of merriment.

Out of office and out of power, Obasanjo had the opportunity to give full rein to his entrepreneurial capabilities. He is very concerned with promoting agriculture and food security in the country to the highest level. He had to seek advice and guidance for processing his poultry products such that the meet the highest international standards required from by foreign fast-food companies. This has enabled him to seek to expand his production beyond Ota farm to other parts of the country and to involve other Nigerian farmers as outgrowers to whom his farm supply improved stocks of birds.

On the social front, being out of power enabled him to give more time to his friends, to attend critical life-cycle events of family members such as naming ceremonies, betrothal and marriage ceremonies and funerals. What his presence at this various events has done, especially where he is made to give speech, is to provide many Nigerians who only read about in the pages of newspapers or see him on formal occasions on the television the opportunity to see and hear him in a normal social context. I have been surprised to hear many people comment after such experience that they did not know that he was such an affable and jovial person. Of course, on such occasions he can be very earthy, lacing his speeches with jokes and local proverbs and sometimes getting the audience to laugh at him.

But, having been in power for all these years, the political situation in Nigeria and Africa as a whole has remained a serious concern of his. This was why soon after leaving office as a military head of state, he could not resist setting up, with the assistance of many international organizations, the Africa Leadership Forum to nurture a new generation of African Leaders.

Initially, the Forum had an office just outside the Ota farm buildings and organised a number of continental meetings and workshops for aspiring leaders from various countries of Africa to which leaders from countries in and outside Africa were invited to lead discussions and give of their own experiences. I was privilege to be at one of those workshops to which ex-President Jimmy Carter of the United States and Mr. Helmut Schmidt, ex-Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany addressed the audience on the challenges of leadership at the national level. I remember Schmidt emphasising the importance of some knowledge of economics aspiring to the leadership of his country.

At the same time, Obasanjo organised monthly residential week-end meetings of selected Nigerians, male and female, from all parts of the country to come to his farmhouse at Ota to discuss various challenging aspects of national development. The discussions were recorded, edited and published as the Farm House Dialogue and distributed widely especially to policy makers.

I was again privileged to be the editor of the Dialogue whilst it lasted. What was interesting to many participants was the manner in which Obasanjo gave the group the benefit of his own critical assessment of their effort whilst in power and what he still believed needed to be done to put the country on the right path with regard to each of the issues being discussed. Given the depth and richness of his experience, participants at both the forum meetings and workshops as well as the Farm House Dialogues always felt they had gained much for accepting to take time off to participate in these encounters.

As the situation in the country became less and less stable, especially after the annulment of the elections 1993 and he himself becoming the target of insecurity in the land, the Dialogue lapsed whilst the activities of Africa Leadership Forum had to be pursued outside the shores of this country. The forum has since returned to the country and is better housed away from the Obasanjo Farms. It is presently an affiliate institution of Bells University of Technology in Ota.

Since leaving office as a civilian President in 2007, Obasanjo’s concern has been with promoting an enlightened environment for multi-party political activities in Nigeria. This has taken the form of greater absorption in back-room activities of his political party—the Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDP). He was made chairman of the party’s Board of Trustees and until his resignation from the position early in 2012, much time was spent in debating, negotiating and reconciling various policy positions among members of the party.

His residence in Abeokuta has become a beehive of political consultations. Not only members of his party in their various factions but also politicians and concerned citizens from all parts of the country apprehensive about the economic, social and security situation in the country troop there on a daily basis. Obasanjo has evinced a patient and tolerant disposition which has come with increasing appreciation of his maturing into the status not just of a statesman but also “Father” of the new democratic dispensation in the country.

Obasanjo’s International Image

From the moment he decided to hand-over power to a civilian president in 1979, Obasanjo’s international image soared. He became identified as someone not blinded by the glittering allure of power but a gentleman whose was his bond. He was someone with whom world leaders could do business. It was thus not long before he was invited to join INTERACTION, the club of former leaders of democratic countries throughout the world. Obasanjo became the first African Head of State to be so honoured. As a member of this club, Obasanjo developed strong personal relations with former presidents or head of governments of countries like the United States, Britain, Germany, France, Japan and so on.

He can thus count among his many personalities such as Mr. Jimmy Carter and Mr. Bill Clinton of the United States, Lord Callaghan of Britain, Helmut Schmidt of Germany and Mr. Jacques Chirac of France. Some of these friends have visited the Farm House in Ota to speak at the training workshops for young African leaders and a number of them have helped to raise funds for some of his projects in this connection. They were in the background of his put forward for the office of the Secretary-General of the United Nations and were very supportive of his decision to accept to contest for the Presidency of the Federal Republic of Nigeria after the end of military rule.

It is not possible to evaluate what benefits this close relationship of Obasanjo with others at the highest level of global political association has brought to Nigeria. Certainly, it cannot be discounted in the almost unique episode of securing significant international debt forgiveness for Nigeria under his Presidency.

That Nigeria no longer has to deploy a sizeable part of her annual budget to meet the claims of a huge and debilitating debt burden is largely due to Obasanjo’s personal relationship with the heads of government in France and Britain at the time. Although the Nigerian Press were disdainful of his frequent overseas trips in pursuit of this goal, they had to concede when the debt forgiveness became a reality that perhaps they had been less than perceptive in their criticisms. There are many other areas in which the high international regard in which Obasanjo is held had redound to the benefit of Nigeria especially, where it had helped to attract foreign domestic investment to the country.

There was thus much international consternation and trepidation when in 1995, the late President, General Sani Abacha, decided to have Obasanjo implicated in a phantom coup d’etat. Obasanjo’s response to this event again was characteristic of his fearless disposition. Although he was out of the country when the news of his likely arrest was making the rounds, and although many of his international friends counselled against his immediate return, Obasanjo decided to brave it and returned to the country. He was immediately arrested and incarcerated for many months.

Numerous attempts were made by foreign government to plead his cause ask for his release. On one of these attempts, my opinion was sought as to whether Obasanjo would agree to a negotiation which would have released on condition that he went on exile from Nigeria and agreed to make no comments on the Nigerian situation while in exile. My response to this proposal drew on my knowledge of Obasanjo’s ethnic ancestry. I opined that the Owu people from whom Obasanjo is very proud to claim his descent were known as brave, stubborn and courageous warriors; that in fact, their usual fighting strategy was for their older warriors to start by knocking a peg firmly in the ground to which they tied one of their legs so that they would not succumb to the temptation to flee at the approach of the enemy.

Thus, I advised that, as an Owu man, Obasanjo was likely to refuse being released from incarceration on those terms. I was thus not surprised that years after his release he confirmed that the proposal was presented to him and he had dismissed it out of his hand as unbecoming.

Equally significant had been the manner in which his personal integrity, forthrightness and resoluteness had made him an authoritative voice in the determination of many continental issues. In his period as military head of state, he had made Nigeria weigh in heavily in support of the political independence of most of the countries of southern Africa especially Angola and Zimbabwe.

In the case of the latter, he had forced the hands of Britain by taking the challenging step of disinvesting in Barclays Bank Plc., one of Britain’s premier financial institutions. It is, of course, well known that Obasanjo was a member of the Commonwealth Eminent Persons Group that began the process of the release of Nelson Mandela, the termination of apartheid and the democratization of the Republic of South Africa. But it is the personal relationship which he succeeded in establishing with most of the primary political actors on the continent that is most remarkable. In a 1995 publication edited by Hans d’Orville in honour of Obasanjo’s 60th birthday and titled Leadership for Africa, Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, the president of Inkatha Freedom Party of South Africa did, in fact, refer to Obasanjo as “The Father of the Continent”.

He narrated his personal experience in October 1976, when the apartheid government of South Africa was about to inaugurate the so-called “independent’’ African states like Transkei within South Africa. Fearing that he, Buthelezi, might be compromised by being made to attend such a farce, General Obasanjo invited him to speak at the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs (NIIA) on the same day as Transkei was celebrating its “circus”.

Buthelezi noted that the other idea behind his invitation to Nigeria was to ensure that he and Oliver Tambo, the then president of the African National Congress (ANC) met on a neutral ground to bring about peace between their two warring parties back in South Africa. Examples of such personal intervention to improve relationship between and among African leaders are numerous and have served to endear Obasanjo to many African leaders in and out of office.

This capacity to foster deep cordial relations with others irrespective of race, colour or creed enabled Obasanjo, as head of the Nigerian government, to put his strong and dynamic stamp on many regional and continental institutions. His term as head of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) saw much forward movement in the challenging mission of building an economically integrated entity out of the many diverse States in the region divided between those speaking English, French and Portuguese. Years after he had ceased to be Head of State, leaders still turned to him in moments of crisis. His leadership was equally critical in giving new life to the Organisation of African Unity which became the Africa Union under his watch and went on to establish NEPAD (New Partnership for Africa’s Development) as a novel vehicle for directing much foreign assistance to the continent.

I believe the tribute of Roelof F. (Pik) Botha in the publication Leadership for Africa, mentioned above, captures much of the international image of Obasanjo that had made him greatly liked by many leaders across the world. Botha was reflecting on the impression Obasanjo made on him as Co-Chairman with Mr. Malcom Fraser of the Commonwealth Eminent Persons Group in 1986. Being a non-black (and an Afrikaner) perspective on Obasanjo, I wish to quote him a little in extenso;

He (Obasanjo) is not a man you would overlook in a crowd. Even from a distance, he is conspicuous and prominent. His large frame compliments his largeness of vision and his breadth of understanding. Anyone who has conversed with him or encountered his speeches, if not live at least in transcript as in Africa Embattled for example, can testify to the dimension of his thought.

I never saw him in a suit. He always wore his traditional agbada Nigerian robe and headgear, often in light green with a touch of embroidery.

I met him on several occasions and enjoyed hours of discussions with him, both official and personal, in South Africa. He came on various missions, which demonstrated the esteem of many world leaders which he clearly commanded, an esteem that even outlasts his 1976 to 1979 achievements as Head of State.

General Obasanjo stood out as the dynamic kernel of the EPG, its hearts and its brain. There was a quiet authority about him. He spoke in a conciliatory tone, avoiding petulance. He reacted to tension with composure. He was mild without being weak, relaxed but by no means lacking in concentration. He was self-possessed, unruffled, striving to soothe heated discussions and able by his presence and manner to do so. He discreetly explored every possible avenue of reconciliation in attempting to bring opposing views together.

I will remember General Obasanjo’s role as that of a leader, a statesman, a man who could talk to you as someone who had gone through the vortex of more than one storm. He had experienced first hand the futility of using violence as a means of resolving problems. He could speak with legitimacy and credibility and carry it with an inner force of persuasion.

Here is an African statesman that deserves prominent mention in the annals of history, a place of honour in any tribute to world leaders.

This international image of Obasanjo has also influenced most non-governmental donor agencies to seek to garner some benefit from his wisdom. Particularly in the United States, Japan and Europe, Obasanjo is on the Board of a number of these agencies such as the Carnegie Foundation, the Ford Foundation and the Sasakawa Foundation. All of this has meant that even out of office he is constantly on the move. His ability to engage in such frequent travels at an age above 70 years attests to a robust good health an agile physical constitution. These travels and the varied purposes behind them confirm Obasanjo’s position as a “true citizen of the world.”

Obasanjo’s Legacy

How will someone with such polyvalent capabilities and innumerable achievements be remembered or would wish to be remembered? Certainly, not simply by way of an epitaph, a monument or an institution, building or streets named in his honour. As a resolute, decisive and innovative person, Obasanjo did not wish to leave his legacy to chance. In his wide-ranging international travels and relationships, he had come to appreciate the significance of the American’s practice of supporting their presidents to institutionalise their legacies through what is now commonly referred to as a “Presidential library”.

A presidential library is, of course, not a library in the conventional sense of a place for storing books and preserving books, journals, papers and so on. Rather, it is a three-pillared institution combining in itself an archive, a museum and institutum. The archive seeks to collate, organise, catalogue and preserve the enormous volume of pre-official documents, papers and reports that a president accumulates over the years especially during his term or terms in office. These are not official or state papers usually found in the legal office of the president. They are materials of a somewhat private nature sent to a president whilst in office, some of which could have informed particular policy or policies but many are simply inform him of goings on in different parts of the country at specific times. They are materials that enrich latter days researches and evaluation of the basis of decision-making or performance of a particular president whilst in power.

The museum element of a presidential library comprises most of the gifts and presents made to a president whilst in office which officially belong to the state. In these are often included other memorabilia of the particular president to enable coming generations capture some flavor of his background and of his time in office. These memorabilia includes for presidents in the United States such item such as their presidential office furniture, vehicles and other personal items which are not likely to be needed by their successors.

President Ronald Reagan, for instance, had the unusual request to have Air Force One, the aircraft that carried him around the world during his presidency presented to his library by the United States Government. The museum artefacts are thus perhaps the most visible elements of a presidential library which make the library essentially an exhibition centre. It is particularly through the display of these many artefacts that visitors to the presidential library, especially the troop of students from educational institutions all over the country, come to appreciate and form their own opinion of the legacy left them by a particular president.

Because a nation still has much to gain from the deep and rich experience of a former president, the third leg of a presidential library is an institutum, an intellectual centre that enables the ex-president to pursue a variety of outreach activities that are of considerable social interest to him whether nationally or internationally. It is now well known that from his presidential library, former President Jimmy Carter of the United States has been able to continue to promote, among other initiatives, a global programme for the eradication of guinea-worm in developing countries including Nigeria. In the same manner, President Bill Clinton’s Presidential Library also has, among other programmes, one for dealing globally with the HIV pandemic and another for contributing to international understanding of climate change.

One of the critical areas of misunderstanding about presidential libraries is their funding. In the United States, the convention is for a president in his closing year of his being in office to establish a private Foundation to raise funds from the public specifically for setting up and operating his presidential library. It is recognised that this may not be as fruitful an endeavour once a president is out of office. Indeed the role of the Foundation in raising fund is not a once-and-for-all time effort.

Even when a president is out of office, the Foundation must continue to raise the necessary funds for maintaining and upgrading the facilities of the library. The fund raising activity of the Foundation in the closing year of the president is not regarded as an abuse of office since, in the event, a presidential library is considered a veritable national asset. Indeed, the government itself accepts to take responsibility for underwriting the cost of maintaining in good conditions both the archives and the museums but not of providing the buildings and the general facilities such as the audio-visual and interactive information technology elements of the library.

The United States Government, for instance, has set up an agency called the National Archives and Records Administration which, among other of its other functions, takes over the white house as soon as the tenure of an incumbent president ends. It then organises the collation and cataloging of all the documents and materials found in the White House, stores them away until the private Foundation of the president is ready with the building where these are to be permanently stored and made available to the public.

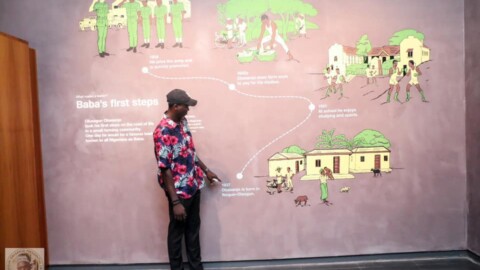

As part of his penchant to be innovative in the area of governance and to ensure that his legacy to Nigeria, Africa and the world is secure, Obasanjo is setting up the Olusegun Obasanjo Presidential Library (OOPL) in Abeokuta. In the words of one of the initial brochures, the project aims at preserving the past, capturing the present and inspiring the future. It is primarily an historic, touristic, recreational and academic centre. Apart from preserving the legacies of President Olusegun Obasanjo, it also houses some cultural artefacts and features essential events in Nigeria and modern African history.

In his characteristically decisive, dynamic and innovative manner, Obasanjo did not wait until a Nigerian Government has come around to appreciate the importance of such institution. He proceeded in his last year in office to set up the Olusegun Obasanjo Presidential Library Foundation under the co-chairmanship of his Excellency, Ambassador Christopher Kolade and his Excellency, Mr. Carlton Masters of the United States. The Foundation presided over the initial raising of funds for the library project in 2006 and continues to solicit funds within and outside Nigeria to complete the building of the library at Oke Mosan in Abeokuta.

To ensure its efficient operation and sustainability over time, the 76-acre Library Complex also houses a guest house, recreation and leisure areas, outdoor amphitheatre, thematic walk, shopping areas and restaurants. Apart from helping to raise part of the financial resources to maintain the Library, these additional facilities are expected to make it a central meeting place for the community and to provide the necessary resources to host international conferences and events.

Already, the Library is hosting the UNESCO Institute for African Culture and International Understanding (LACIU) which is committed to preserving Africa’s cultural heritage, promoting and strengthening the renaissance in African cultures at both the regional and international levels, and increasing inter-cultural dialogue and international understanding between Africa and other civilisations.

The hope is that the Olusegun Obasanjo Presidential Library will be ready for commissioning in 2014, as part of the events marking the hundred years of emergence of Nigeria as a single polity following the amalgamation of the Northern and Southern Protectorates and the Colony of Lagos. The collation and organisation of archival materials have reached an advanced stage. The ambient environment for their preservation cannot be in place until the Library building is completed.

The museum and its exhibition facilities are also in the process completion to effectively display the numerous artefacts that chronicle the extraordinary story of Obasanjo’s life – his humble beginnings in Ibogun, his military career, his ascent to military head of state, his incarceration and his eventual election to the Presidency of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. It will also document the high esteem in which he held internationally especially because of his commitment to democracy as evidenced by the numerous invaluable gifts presented to him in many countries of the world.

As for the institutum, Obasanjo indicated that his interest is in pursuing all issues relating to human security, especially on the African continent. A Centre for Human Security is thus the third pillar of the Olusegun Obasanjo Presidential Library. Human Security as a concept, is however, very difficult to define briefly. The World Bank sees it simply as a capacity for “reducing vulnerability’’. The Centre, however, prefers to adopt the definition offered by Dr. Sabina Alkire, which conceives human security as concerned with “safeguarding the vital core of all human lives from critical pervasive threats in a way that is consistent with long-term human fulfilment”.

This vital core embraces security in such areas as food provisioning, health-care, education, environmental quality, cultural integrity and so on. The Centre has already begun research and developmental activities in these various areas and has over the last three years successfully held a number of workshops and conferences on some aspects of human security. It is also considering other outreach activities especially in the areas of leadership in Nigeria and Africa as well as promoting continental excellence in various areas of human endeavour.

It is thus interesting, that a section of the Nigerian press not fully understanding what a presidential election is all about, launched out a negative campaign when the project was being initiated. However, as many Nigerians came to appreciate and to see at first hand the development of the multifarious parts of the Library Complex, opinion has been changing towards acknowledging the foresight and visionary stature of the man Olusegun Obasanjo.

His Presidential Library, when commissioned, will not only help his legacy in a manner beyond words but also provide coming generations a rich, assured, physical and substantial evidence of the highly endowed and multi-valent personality, a passionate Nigerian and an African patriot, a highly respected statesman and citizen of the world that was once the president of this great country.

Conclusion

It has been difficult to do a full justice to a veritable characterisation of the man Olusegun Obasanjo. How does one balance the controversial recognition of his greatness as a Nigerian leader within Nigeria and the world’s acclaim of him as towering leader and statesman? How does one reconcile his numerous undeniable achievements as a president with the Nigerian media’s negative posture to his accomplishments over the years of his presidency? How does one resolve the fact that it has not been possible to tarnish his personal reputation for being incorruptible with the virulent media campaign that he must be probed even when it is obvious that if there was any basis for the campaign it would have slipped out into the public arena since he left office?

What, of course cannot be denied is that the man Olusegun Obasanjo whether in office or out of office, has been a strongly outspoken voice for change and a decisive, resolute and dogged actor for reform in numerous areas of national life. It is perhaps this fearlessness and outspokenness in promoting change and innovations that can, at least, explain in part the acute difference in the perception of his greatness by the outside world and a section of the Nigerian community. I believe Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527) probably has the last word in defining a man such as Olusegun Obasanjo. To quote him:

“There is no more delicate matter to take in hand, nor more dangerous to conduct, nor more doubtful of success, than to step up as leader in the introduction of change. For he who innovates will have for his enemies all those who are well off under the existing order of things, and only lukewarm support in those who might be better off under the new order; this luke warmness arises partly from fear of their adversaries, who have the laws in their favor and partly from the incredulity of mankind, who do not truly believe in anything new until they have had actual experience of it. Thus, it arises that on every opportunity for attacking the reformer, his opponents do so with the zeal of partisans, the others only defend him halfheartedly, so that between them he runs great danger.”

Only time can deal with this danger. But for the world as a whole and the majority of Nigerians, it will be difficult to deny greatness of the man, Olusegun Obasanjo, and his towering position in the history of the Nigerian nation.

Source:

Olusegun Obasanjo, The Presidential Legacy,

Vol. 1, BookCraft, 2013 pp 2-26.