By Sam Akpe

The book is big – a little over 700 pages. But it’s in no way scary. If you love excellent, descriptive, and thrilling prose, you will definitely love this book. Every page and every chapter is filled with daring, investigative reportage – the type with the capacity to generate envious applause or deadly repercussions; or both.

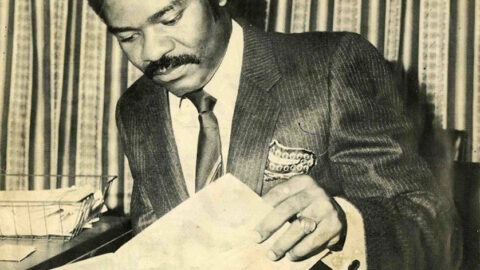

Surely, this is a book of reading. The size notwithstanding, it is a piece of appetising literary cake. Audacious Journalism, a compilation of timeless writings by Anietie Usen, has been long time coming. It covers and brings to remembrance the 80s’ crucial issues from the local communities of Akwa Ibom State in southern Nigeria, to matters of national importance in the Nigerian nation.

Just when you think that’s where it ends, Usen takes you into the tempestuous belly of the West African sub-region reporting wars and political instabilities, before focusing on the despotic sovereignty of some rulers and events across the African continent. Then, with what could be termed uncommon boldness, he walks straight into the Arabian Peninsula covering wars and rumours of wars; dodging bullets, escaping bomb blasts and living to tell the tales. His reports and commentaries on American, British and Russian issues are fully reflected.

Audacious Journalism defines journalism in the original mannerː an audacious profession for audacious practitioners. This is not an arm-chair definition; narrated after years of academic research. No! It comes from years spent at the front-line of practice or what American footballers call the line of scrimmage. It is authoritative.

The man who should write the foreword to this book – and who actually did – Professor Des Wilson, describes it as “an encyclopaedic escapades and a collection of thrilling stories…reflecting both (Usen’s) eclectic interests and the body of assigned duties.” Again, that’s authoritative.

The clear difference between what Usen has captured in one volume and what historians and researchers would ever write on the same issues is that he personally witnessed those events. He saw and reported the wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone; covered elections in Benin Republic; interviewed most of the despots in Africa; witnessed bombs explode in the Middle East where he interviewed unsmiling Taliban leaders in caves at night; and covered bloody military coups in Nigeria. What a job!

The book’s contents come in parts; there is the beginning entitledː To Start With. That is the appetiser. It is followed by Nigerian issues which covers more than 300 pages. Next are the columns; followed by reports from Africa, America, other parts of the world; interviews, and sports.

One of the unforgettable investigative reports ever published in the defunct star-studded Newswatch magazine was entitledː Right Name, Wrong Person. It is a story of mistaken or confused identity; a product of faulty public service appointment procedure in Nigeria. A government announcement had appointed a certain A.S. Inyang as a member of the Constitution Review Committee. One month after a school headmaster, Asuquo Sam Inyang, was sworn in amidst celebration and a five-star treatment befitting his office, Usen reported that the real appointee, Anyang Sylvester Inyang surfaced. Confusion, embarrassment and humiliation replaced the initial celebration.

Usen’s investigative skill is further proven in The Crash of Flight 086. This is not a story to read while flying or preparing to board a flight. It is as frightening as it is detailed in facts and imagery. It is the story of the 1996 crash of an ADC (Aviation Development Company) airliner; a Boeing 727 carrying 143 persons. The aircraft plunged into a lagoon in Lagos, killing everyone on board. Usen, in this report, goes beyond the line of “normal” reporting to analyse and interpret technical reports, unearth hidden facts – not just about ADC plane crash, but how human failures have often led to the death of thousands of aircraft passengers.

Usen writes in picture words, a typical Newswatch house-style. That is, when you read most, if not all his writings, what you see are pictures emerging from each word and each sentence. In Abacha’s Last Hours, Usen employs that literary concept called imagery to construct Abacha’s moment of glory in one paragraph and a sudden inexplicable crash in the other. Imagery in literature is a product of descriptive prose. This is a terrain Usen has a commanding authority. He picks his words carefully and recreates scenes with them.

With this, he pulls the reader mentally into the arena and allows him to “see” The Prison In Hell, a story that will make you cry over the conditions of prisons in Nigeria. It starts with, “the man died just before lunch. A plate of beans pottage kept at the foot of his hospital bed was covered with flies. His sore mouth and sunken eyes were barely closed. The rusty leg-iron that fettered him to the bed had left his right ankle badly bruised and swollen. From a distance one could count the number of his ribs…. Life in a Nigerian prison is hard, inhuman and cruel.” This story is followed by A Prison To Desire which describes the prison conditions in Cardiff, capital of Wales in the United Kingdom. What a contrast!

In The House That Quacks Built, Usen unveils his reportorial dexterity in another dimension. He employs short sentencesː “Blood soaked clothes. Crushed pieces of furniture. Twisted iron rods. Broken pots, plates and rubble. These are all that remain of House 26, Idusagbe Lane, Idumota, Lagos….” With this, he picturesquely leads the reader into a well-investigated story of accumulated tragedy called collapsed buildings. This is a tragedy that has “turned some schools into the valley of the shadow of death,” and turned residential accommodations into living hell. Across the country, the story paints pictures of houses built on sand.

From collapsed houses, mostly in the south of Nigeria, this multiple award-winning reporter takes the reader to “a scruffy, little village of thatched huts” in Kaduna State where the “streets are narrow and dusty” and “most natives are shaggy and scraggy”. Reign of Gemstones Bandits is a story of economic sabotage. It paints an embarrassing picture of porous borders that continuously admits illegal miners from other West African countries into Nigeria.

Human interest stories are Usen’s delight. When the narrative focuses on humans in their habitat, or when nature deals a blow on the defenseless, Usen leaves the reader wondering whether to cry or be thrilled; or both; as in The Rage of Heaven. Another one is Mission To Iko; embellished with acceptable metaphoric hyperboles (that’s a mouthful). He writes about a market at Okoroete village where “there were about 23 people….” Then, “a tiny canoe, as deep as a flat plate and paddled by a 10-year little girl,” across the river. The girl gave him a small calabash basin. For what? His duty was to fight back and scoop out the water flushing into the canoe violently, as she meandered her way along the creek.

A must-read for all parents is University of Criminals. It surely chills the bone marrow. It is a story of extreme acts of inhumanity by children of the rich and mighty. Usen presents raw facts about the dare-devil acts of secret cult members. The story is filled with terror, blood and death. It continues in Bad Day for Bad Boys with focus on the present University of Uyo. The Arts of Exam Malpractice is a detailed reportage that spares nobody: students, parents and teachers. Names are mentioned and offences identified.

Audacious journalism has a way of repeatedly putting the practitioners in trouble. Ray Ekpu In the Dock is told in a typical Usen’s daring style. He notes, reports and analyses every comment – minor and major – an aspect of reporting usually, easily ignored by the inexperienced reporters. Tale of Two Editors exposes the risks involved in editing government-owned newspapers while The Pen Against the Gun is another narrative on the risks of audacious reporting; particularly under the military. It chronicles how certain editors were usually arrested, detained, jailed or even publicly flogged; as in the case of ten staff of the Yobe State-owned television service. They were arrested, taken to the Government House and flogged under the direct supervision of the military governor, John Ben Kalio.

Remember Alozie Ogugbuaja? He once described the military as “the unregistered party of Nigeria” whose employees “are overpaid, drink beer and pepper soup quite early in the day and do nothing else but plan coup.” He is captured in Officer and a Radical.

Style! That beautiful, grace-filled word is delightfully applied and splashed all over the book. Add this to Usen’s descriptive prowess and depth of analysis, then you’ll love the piece entitled: Eze Goes to Villa. When it comes to political reports, Usen has the undeniable touch. He brings this to bear in the article entitled A Despot and the Pope. The reporter, in The Making of A Saint, did a front-row report on the canonisation of the late Father Cyprian Michael Iwene Tansi, the Nigerian monk who died in England in 1964. His 34 years old corpse was exhumed a week before the arrival of Pope John Paul in Nigeria. Usen witnessed all of it.

The risk of audacious journalism is again captured vividly in The Fear of Bomb. Usen writes, “At Peshawar, the border town between Afghanistan and Pakistan, we returned home one evening to discover to our shock that part of our hotel complex had been ripped off and brought down by a bomb. The bomb did not come from the sky. It came from a hair salon on the ground floor of the rebels infested hotel.”

Writing a column has never been easy. I guess I should know. But when you read Warfront By Another Name, you become scared the more. The piece is full of history. While the focus is on road accidents caused by a certain brand of automobile called J5, there is rich background information on the evolution of motor vehicle. The Silver Lining is a story on endurance. It highlights those who failed many times in order to succeed in unbelievable ways.

Just as it is in raw news presentation, Usen’s columns in the Pioneer newspaper are well-researched. He educates the reader on issues with uncommon historical perspectives before arriving at his destination. In all his columns, his personal opinions are about 10% or less; while background information and analysis of issues constitute the remaining 90%. This is the dividing line between experienced writers and interns. You do not force your uninformed armchair opinion on people. You allow them draw conclusions based on comparative analysis of historical and current events.

As the book draws to a close, Usen’s experience as an international affairs reporter remains unquestionable. From Africa to the West and the Far East, he knows and understands the terrain.

However, in reading Audacious Journalism, if you are the over-meticulous type when it comes to the rather technical arrangement of books in chapters, then you will have a few questions to ask Usen and his publishers. Each article has a title but the entire book lacks chapters. That again, may be a style.

In addition, this is a compilation of past writings. And every book in this category is expected to have dates attached to each piece for purposes of authenticity. The dates are usually either placed below the headlines (as in Winners Take All by Alade Odunewu) or at the end of each piece (as in Diary of a Debacle, by Olatunji Dare; Suddenly, by George F. Will; or Dialogue With My Country, by Niyi Osundare). This book lacks that also.

By the way, in a compilation of this nature with pieces assembled from different sources, it would have helped the reader if such sources were identified either at the beginning or end of the each piece. For instance, it’s difficult to know which piece was published in the Pioneer newspaper; or the Newswatch, Africa Today or the Punch except in rare cases where the identification is made in the story.

Mark my words; none of these, in any way, distracts the reader from the art, the style and the depth of Usen’s writings. They are individually rich in professionalism and unquestionably courageous. The book evokes the nostalgic feeling for daring reporting of yore.

Yes, Anietie Usen has finally done what he should have done years back. But this is just the beginning. He has simply succeeded in wetting our literary appetite after a long wait. The world is still expecting the other two booksː The Art and Practice of Political Reporting; and Covering Wars and Living to Tell the Tale.

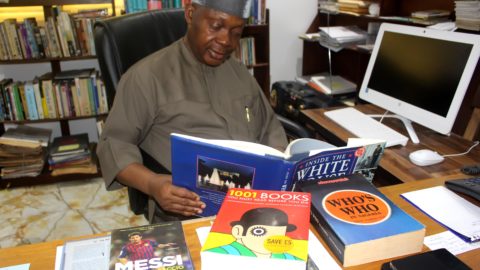

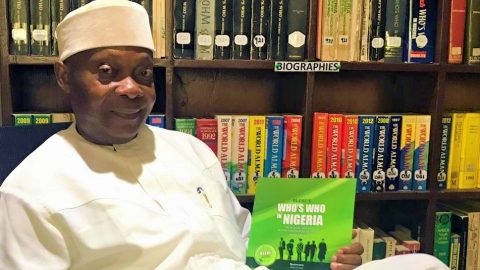

ABOUT THE REVIEWER

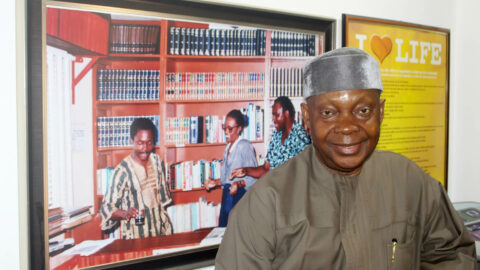

Sam Akpe, a good friend of BLERF and a prominent and well-informed journalist, has worked with the influential Punch newspaper (1998-2007) where he covered and wrote a weekly column on the Senate from 2002 to 2006. He later joined the Daily Independent as deputy editor (2007-2014).

Akpe maintains a column with the Niche, an online newspaper, and does weekly political interviews for The Point.

In 2014, he served as Rapporteur (later, Special Assistant, Media and Communications) at the National Conference. He has also been involved in media specialisation with impressive experience in corporate communication practice.

A husband and a father, Akpe loves books and has contributed chapters in published works. Alongside other professional training, he holds a post-graduate degree in mass communication.