Written By Ray Ekpu

In the Newswatch issue of March 8, 2004 I had written a column on Obong Victor Attah, who was the Governor of Akwa Ibom State then. In that article I said: “The big man I was talking to at the Aso Villa, Abuja, simply looked away from me and blurted. This mad man don come again.”

I looked in the direction of his gaze hoping to find a shaggy-haired man in rags muttering undecipherables to himself. Next, I was going to ask how a mad man managed to beat the multi-layered cordon-like security at the place. Not seeing anyone who made the grade I had to ask who the mad man was. “Your governor” he promptly replied. “Why,” I asked. “Oh every time he comes here he harasses everybody, “resource control, resource control.”

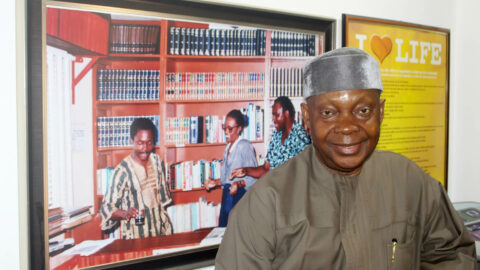

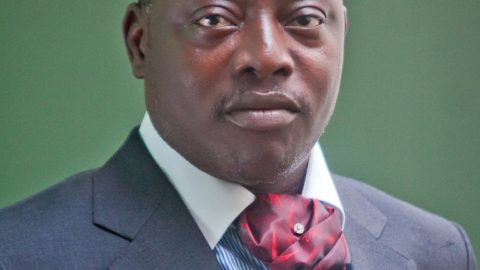

I chuckled to myself in self-satisfaction knowing that the battle had reached home and even the walls of Aso Villa had reverberated from the verbal fire power of Obong Attah and the rest of the activists for equity and fairness in the oil-rich and tragically marginalized region. I remember this story because the doughty warrior, Attah is today a registered member of the octogenarian club and this article is my tribute to this forensic warrior.

Obong Victor Attah comes from an illustrious, aristocratic family in Akwa Ibom State. His father Chief Bassey Udo Adiaha Attah was one of the six young people sponsored by the Ibibio Union for studies in the United States and Britain in the nineteen thirties.

He became the first Nigerian to earn a bachelors’ degree in Agriculture from abroad. Obong Attah’s mother was Madam Agnes Bassey Attah, she was a school teacher who co-founded the Ibibio Women’s Union and became its first President. Coming from such aristocratic background Obong Attah’s educational path was paved with gold.

He studied architecture and building science in Nigeria, Liverpool University in the UK and Columbia University in New York. He was a registered practitioner of his trade with the State Licensing Board in New York. Attah, a fellow of the Nigerian Institute of Architects and its past president has done mega projects of architectural significance such as the University of Calabar masterplan. He also did major projects in Trinidad and Tobago.

For most people who know him, Attah’s real essence is to be found not necessarily in the offices that he held but in the valiant battles that he fought. Yes, he was the Governor of Akwa Ibom State for eight years.

During this period he built roads, fixed potholes, sank boreholes, provided schools and hospitals and electricity and generally improved the well being of his people.

The landscape enjoyed a significant face lift in the various local communities. It is appropriate to say that he laid a solid foundation for the transformation of Akwa Ibom State. That is why his admirers consider him the father of modern Akwa Ibom. Akwa Ibom is a work in progress and as the state grows there will be many more significant fathers in the near or far future.

For me Attah easily stands out in two admirable ways. One is that before he came into office as Governor of the State, Akwa Ibom people were generally perceived as backward, superstitious and timid. They would not demonstrate either for or against anything good or bad and it was easy for them to be oppressed without their lifting a finger in protest.

They seemed to fit into the mindset of those that Fela ridiculed in his song “I won build house, I don build house. They could be flocked and they would look at their tormentor like mumus, zombies, donkeys, no protest, no punch in return, no carrying of placard, no letter to an editor, no filing of a suit in court, nothing, absolutely nothing.

It was Obong Attah who taught his people the art of protest, the demonstration against oppression not only by preaching to them about the advantage of dissent. He went further than just talk. He was a conscientious dissenter.

In the fight for justice, fairplay and equity in the Niger Delta, Obong Attah with such men as DSP Alamieseyeigha, James Ibori and Peter Odili put up a fierce fight with the Olusegun Obasanjo government. They engage Obasanjo in legal and political battles while the boys with AK47 did their own duty in the creeks.

These combined forces brought Obasanjo to the negotiating table. In the days of Isaac Adaka Boro., the strategy was principally physical and the search for a Delta Republic was a misplaced distraction. But Ken Saro Wiwa was better equipped for the battle because he had a long intellectual antennae reaching from the Niger Delta to the United Nations.

Attah is a warrior and a philosopher. It is the right combination for liberation battles because of those who must be convinced about the need for battle. As Rick Fields said “warriors have a mission beyond themselves.

The true warrior is dedicated to something greater than personal survival and comfort.” Attah from a well-heeled family did not need the Niger Delta battle to survive. He could have survived satisfactorily in his comfort zone, lapping up whatever luxuries his education and family could offer and leaving the crunchy battle to those who needed the spoils of war better than he did.

Attah is a man of character, he cherishes it, he guards it. He knows that fame and fortune are epheremal and can evaporate easily but character endures. That is why in his eight years in office no one could truly accuse him of being an aggressive acquisitionist or a man who engaged in illusions of grandeur.

He comes from the upper crust of society, the champagne club, the yatch club, the private jet club but he lives an admirably simple life. By his family pedigree and his own he ought to have his nose in the sky, but he doesn’t. he is disarmingly simple, there are no airs about him, no superiority complex, no aloofness. But make no mistake about it, he doesn’t suffer fools gladly.

He always says his mind in a linear fashion, no circumlocution. He is invigorating company, full of charm and good humour, a good raconteur and conversationalist, a good Catholic who quotes the Bible copiously. He has a rich stock of Biblical and secular stories with which he garnishes his public and private conversation.

With him there is no dull moment. He has an unerring gift for going straight to the point for making his point forcefully with appropriate anecdotes thus raising political rhetoric to high art.

Most Akwa Ibom people address him as Ette, meaning father or leader. But he is now being reverentially called Ette Nnyin, that is our father, our benevolent uncle. That is the evidence of the veneration that he has earned not based entirely on age but based largely on his achievements, his carriage, his comportment and his place under the Akwa Ibom sun.

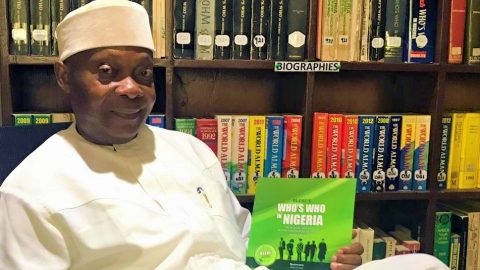

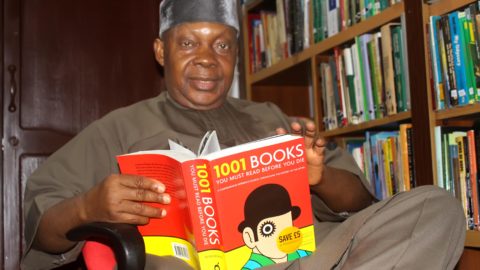

Attah is a lover of knowledge and the people who have it. During the battle for resource control he utilized all the knowledgeable experts in his government. When he thought he needed more help he set up a small committee headed by Senator Udoma Udo Udoma who was Chairman of the Appropriation Committee at the time. Mr. Udeme Ufot, Managing Director of SO&U advertising company was in that committee. So was I and together we provided him with alternative policy options on the ticklish issue which he deeply appreciated.

We too felt honoured that we were asked to contribute our quota towards the resolution of the problem that was gnawing at the vitals of the Niger Delta people. That says something about the quality of his government: an inclusive government, one that was not afraid of searching for solutions to problems from wherever they could be found whether within or outside his government.

There have been arguments over the years about Attah’s achievements in Akwa Ibom as Governor. In an atmosphere of partisan politics such discussions get besmirched by the miasma of partisanship. For me his real achievement lies principally in the transformation of the Akwa Ibom mindscape even more than its landscape.

The mindscape can improve the landscape but not vice versa. The landscape can easily degenerate but not the mindscape. The nourishment that the mindscape receives from regular contacts with a generally improved mindscape is immeasureable. But the problem with Nigeria is that everything seems to be measured almost wholly and solely by naira and kobo.

The other imperishable legacy of the Attah tenure is that he taught the Akwa Ibom people the art of war. War does not always have to be physical or violent. The crunchy search for justice, fairness and equity may involve confrontations that can be categorized as war. Complacency is a defeatist strategy in Nigeria.

If you want something fight for it. That is one of the rules for success. No one will give you what you want in Nigeria in a wrapped package with a nice ribbon tied round it. Attah taught that that is the way to go.

Who can be right if the octogenarian is wrong?