Review of The Nigerian Century

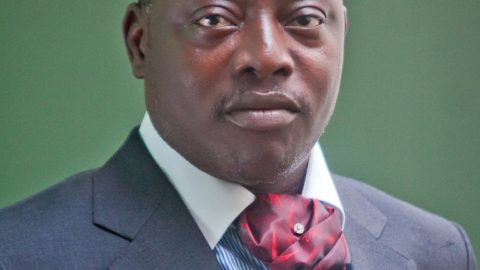

BY SAM AKPE

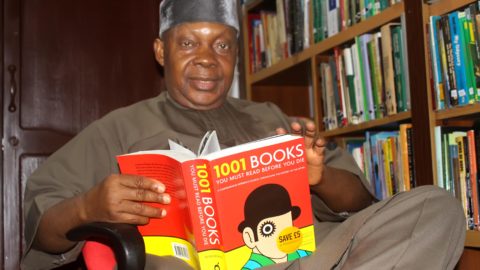

Wow! This is a book to buy and keep—the type you will repeatedly pull off the shelf for another perusal! The texts, the pictures, illustrations and the layout are enticing—more so for students of aesthetics.

The book, The Nigerian Century, is factual, innovative and loaded with well researched and breezily written stories about Nigeria, this book takes us back at least 100 years and boldly tells us why we are where we are today.

It is a story of a forced political marriage; a story of our rise and fall as a people; a summarised version of a long history that pre-dates the creation of Nigeria in 1914. It is a recapitulation of a century-old salient journey—the journey of a people diversified in tongue and tribe.

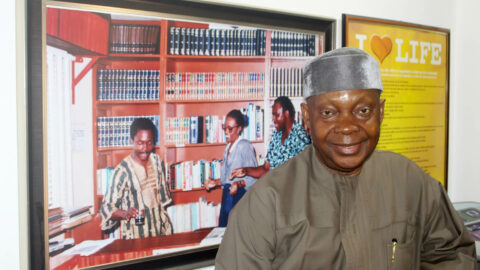

Pioneered and edited by an extra-ordinary writer and columnist, Dare Babarinsa, my attempt at reviewing this book was a big risk for several reasons. First, who am I to unveil the intellectual thoughts and the literary ingenuity of a big journalism masquerade in the mould of Dare Babarinsa? Second, who can edit this editor who has produced several editors and has edited most of them?

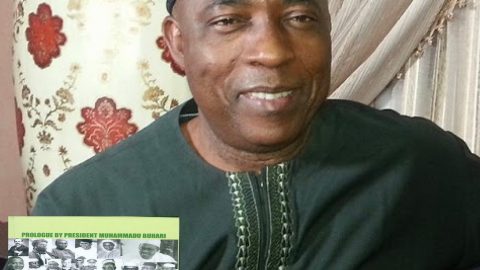

Published to commemorate one hundred years of Nigeria—from 1914 to 2014—you may likely ask: how did this publication escape my notice for so long? From the prologue by President Muhammadu Buhari to the epilogue by his former military boss—Olusegun Obasanjo—every page of this book is a walk into the rich history of our country, an analysis of where we are, and a peep into a beckoning future. You think you know Nigeria? No! Not until you have read this review of our history.

As you open each page of this extraordinary book, many questions will flood your mind—as it did mine: How did we get ourselves into our present condition? How did we even come together as a country? Who got us into this marriage of inconvenience? With such a rich—though not perfect—past, how did we get into this seemingly helpless economic and political entrapment—and how do we get out?

All the answers to these questions are definitely not in this book because it was not written to successfully answer such questions; but as one approaches the narrative with an open mind, a small voice keeps whispering: a beautiful future is possible. We may not be able to rewrite our history, but we can re-conceive and re-nurture the future.

The book, The Nigerian Century, is not just a collector’s item (as the cliché goes), it is a national history featuring people, politics, economy, sports, youth, culture, technology, etc., under one literary roof. In the words of President Buhari, this book is the story of a nation “born in adversity (and) nurtured to adolescence in the rigours of the colonial period…” It is also the story of a country, which, in the living words of another military dictator, Ibrahim Babangida, has had “a history mixed with turbulence and fortune.”

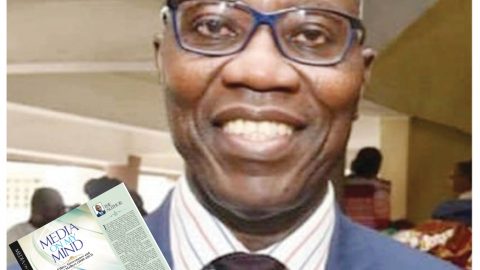

Designed and published on an A4-size paper, the book has 519 pages. The project editor, Dare—as he is known by friends and colleagues—is a veteran reporter and was editor at the Concord newspaper, Newswatch and TELL magazines. A media entrepreneur and a newsroom historian, Dare’s understanding of Nigerian history goes beyond academic discipline. It is a passion.

When you read The Nigerian Century, you are taken from the present into the past with amazing ease of understanding. Dare brings to bear in this book not just his literary skill, but his information network and contacts within and outside government.

As you savour the cerebral aroma flowing from each page, it’s easy to conclude that this book is a product of a competent team of excellent writers, mature editors, skilful researchers and consultants; with Dare at the top of the pack. This is where you read history written as news.

If you ever thought that Nigeria has no story worth telling, you would be persuaded otherwise after reading this book. At the end, you will either rejoice at this “great country that defines the African continent and holds within its destiny the future of the black race,” or shed tears on realising that “we have (repeatedly) witnessed our rise to greatness, followed with a decline to the state of a bewildered nation (because) our human potentials have been neglected, our natural resources put to waste.”

It is to the credit of journalism—particularly female journalists—that the person who conceived the name Nigeria to describe the geographical blend of 1914, was a female journalist. The narrative in this publication with a focus on that incident is headlined: Marriage at Gun Point.

The story explores the ingenuity of Lord Frederick Lugard and his mistress, Flora Shaw, in the amalgamation process. This process was consummated at the Race Course in Lagos, later renamed the Tafawa Balewa Square.

The two-page thrilling piece authored by Dare is rich both in words and in pictures. It explains why Nigeria’s first capital city—Lagos—was preferred by the colonial masters in London although Lugard was more in love with Kaduna and had put pressure on the Queen of England to accept his suggestion.

The Dawn of Nationalism, the second story in the book focuses on Herbert Macaulay, a journalist, who personified the huge resistance against colonial rule in Nigeria. Trained as a surveyor, he took to politics by choice; drawing inspiration from his grandfather, Samuel Ajayi Crowther, the first African Bishop and founder of Nigeria’s first political party, the Nigerian National Democratic Party in 1923.

Let’s pause for a moment here. Think about this: journalists are the greatest but most often-ignored patriots in this country. For those who take delight in treating journalists as third class citizens by playing down their role in the political stability of Nigeria, this book should challenge their thoughts and actions.

This is because Nigeria’s history, from 1914 when the amalgamation took place, to the early days of nationalism till independence in 1960, featured journalists in the forefront of the struggle.

As earlier stated, the name, Nigeria, came from a journalist, Flora Shaw. Again Herbert Macaulay, the man who first led the battle against endless colonial rule in Nigeria was a journalist and a publisher. Two of the early days nationalists who came to prominence on the platform of Nigeria Youth Movement—Samuel Akinsanya from the present Ogun State and Ernest Ikoli from the present Bayelsa State—were journalists.

What about Anthony Enahoro—who moved the historic motion for Nigeria’s independence? He was a journalist! Then the biggest and most influential of them all, Nnamdi Azikiwe, founder of the National Council for Nigeria and Cameroun. He was a fire-brand journalist with ownership of a chain of newspapers across the country. Just a food for thought!

The story entitled: Rise of the Three Musketeers chronicles the nationalistic lives of three of Nigeria’s most recognised and respected political activists—Nnamdi Azikiwe, Ahmadu Bello and Obafemi Awolowo.

This beautifully narrated short report equally suggests the rise of ethnic politics in Nigeria since each of these musketeers had political dominance in their different regions. All of them led different political parties—Azikiwe had the NCNC, Awolowo had the Action Group while Bello had his Northern Peoples’ Congress.

One clear revelation in this story is that though the three nationalists operated on different political platforms and adopted different approaches, their mission remained the same: to free Nigeria from the stranglehold of Britain.

Also, despite whatever ethnic colouration their politics painted, their activities were not absolutely ethnic-based. In fact Azikiwe was at a time, the opposition leader in the Western House of Assembly in Ibadan. Those days are far gone! Those were the days of one nation, one destiny.

The story of the three men of destiny continues in another chapter under the headline: The Race to Independence. Here, the authors point out the unique selling points of each of the nationalists. In the southwest, Awolowo introduced and sustained the free education agenda; in the east, Azikiwe embarked on education development and creation of urban centres; while in the north, Bello gave agriculture and education a fresh thrust.

However, attaining independence for Nigeria was their primary focus. On October 1, 1960, the British flag, called the Union Jack, was lowered for the last time at the Race Course, Lagos. This epochal event also marked the emergence of new leaders including two outstanding journalists, Tony Enahoro—who moved the motion for self government—and Chief Ladoke Akintola.

This was how Enahoro opened his motion in 1953: “Mr. President, I rise to move the motion standing in my name; that this House accepts as a primary political objective, the attainment of self-government for Nigeria in 1956.” That opening sentence rattled the entire structure of the colonial government.

However, with independence in 1960 also came a “gathering storm in the horizon.” And what was the storm? The next chapter entitled: A Turbulent Ride to the Twilight, tells it all. It is the story of internal wrangling within a once-stable political party that led to divisions and breakaways.

In the west, Awolowo and others were arrested, tried and jailed for treasonable felony. The book does not offer much detail in terms of what led to such high crime allegation. But it talks about a political turbulence that humbled every other politician in the country.

The book indicates that if Nigeria’s political environment was messy in 1962, the federal election of 1964 made it messier because it “was the civilian equivalent of war.” People died. Properties got burnt. Blood flowed on the streets; all in the name of politics.

To worsen the matter, the regional elections of 1965 created such bloody and corruption-ridden atmosphere that led to the January 15, 1966 military coup, which kicked the First Republic “into the dustbin of history.”

The story of the coup and counter coup which snowballed into a 30-month civil war is told under the headline: Darkness and the Civil War. It is a story of political miscalculations, vengeance, plenty of death and tribal sentiments taken too far. This is one gruesome incident that has left a life-time scar on Nigeria. It was not unavoidable. But driven by the greed, vengeance, misplaced annoyance and show of ethnic superiority, the perpetrators pursued it with passion.

Within this period, top political leaders were slaughtered; the civilian government was sent packing by military leaders, ethnicity found its way into the Nigerian military vocabulary when Aguiyi-Ironsi was killed on the excuse that his kinsmen staged the military coup. Yakubu Gowon was enthroned as head of state; while Emeka Ojukwu and others planned and sustained a secession that resulted in the civil war.

Thirty months after the war started; and Ojukwu had left Nigeria “in search of peace,” his second-in-command, Philip Effiong on Monday January 12, 1970, made a broadcast that brought the war to an end. He declared in part, “I am convinced now that a stop must be put to the bloodshed which is going on as a result of war. I am also convinced that the suffering of our people must be brought to an end.”

So, the war ended. But the real end of that bloody journey was the overthrow of General Yakubu Gowon in a bloodless coup led by, among others, Colonel Joseph Garba, the Commander of the Brigade of Guards. It was more of a palace coup.

The 1976 assassination of General Murtala Muhammed who succeeded Gowon in 1975 ended what the book describes as “almost a new beginning.” Murtala had stormed the scene with a bundle of brooms to sweep away corruption. He also announced a transition plan to usher in democratic governance.

Despite what looked like a bright future under his leadership, he was killed in a coup led by a certain Lt. Col. Bukar Sukar Dimka on February 13, 1976; and was succeeded by Obasanjo who continued with the transition programme and handed over power to Shehu Shagari in 1979.

There is something about this book that thrills beyond the rich, summarised historical information. Pictures! If the editorial content is short, it is only because there are innovatively selected pictures to tell the story in ways words alone cannot.

There is this picture on page 20 showing lawmakers trying to escape through the windows during crisis in the Western Region House of Assembly. There is another one on page 21 showing Chief Okotie-Eboh and wife flowing in their glory. Both tell more stories than words.

TO BE CONTINUED IN PART 2