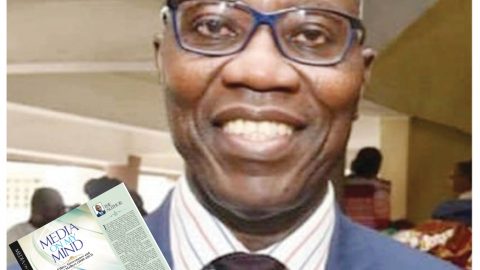

Review of MEDIA ON MY MIND

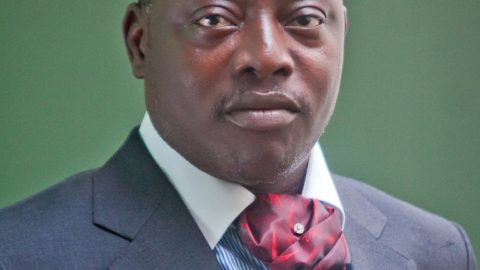

BY SAM AKPE

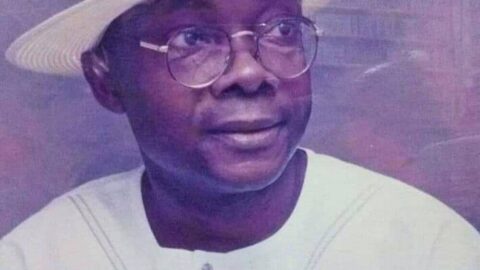

This book is exceptional for specific reasons. Yes, the focus is journalism; and it is written for journalists. But more significantly, it is written by a journalist—not just one of them, but someone moulded through journalism classrooms, tested and toughened through the mill as a reporter, researcher, writer, editor, publisher and a teacher of journalism.

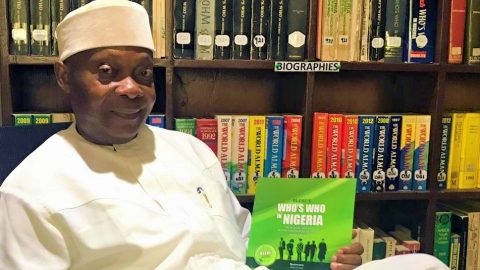

Not many authors of journalism books boast of such divergent but mutually benefitting credentials. Described by Adebayo Williams as “an enigma wrapped inside a conundrum…” Lanre Idowu is both “the preceptor and the practitioner of journalism.” Rare breed!

You can then appreciate the dilemma I faced as I opened the book: Media on My Mind. I started wondering: which of these is appropriate to review: the book or the author. This is because Lanre—as his contemporaries call him—has become an institution on media issues. His fame is bigger than his frame.

Your knowledge and perception of Lanre depends on where you had an encounter with him. Outside the newsroom, you could have met him on the pages of Media Review—a publication solely dedicated to analysis of media issues. You could also have met him at journalism workshops and training schools.

It doesn’t end there. What about meeting him at the Nigerian Guild of Editors conferences? Maybe it was at the West African Media Awards Programme; or at the University of Lagos, or Fordham University in New York. Wait a minute, what if you met him at the annual Diamond Award for Media Excellence or through his columns in the newspapers?

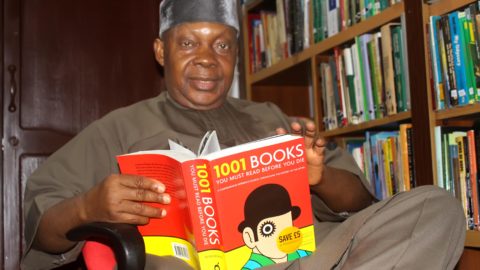

However, the most assured avenue—if you missed any of the above as I have—would be through his books. Yes! Books cover distances. Books can reach where writers can’t. A book is an extension of the author—his thoughts, credibility, professionalism and personality. Lanre has his name on quite some books.

Media on My Mind is a collection of articles and public comments by Lanre, previously published in Next—a breezy, gutsy Nigerian newspaper that disappeared as mysteriously as it appeared; leaving a delicious taste in our mouths. Others were published in Media Review—an audacious monthly that has won him accolades and made him not a few enemies in the industry.

Media Review came in the shape of a journalism puritan whose rigid adherence to the traditions of the profession in reportorial, headlining and the body text is sometimes scary. Can we deny that Media on My Mind is an extension of Media Review? Let’s leave it there for now.

Media on My Mind has 106 chapters divided into 12 sections. Under ethics, certain general issues are discussed including specific ones such as the Case for Media Regulation and Enriching Reporting. Under governance, we have the Presidency and Elections. Others are the New Media; Terrorism; Professional Hazards, Peoples and Institutions; Language Use; Book Reviews and Interviews.

The book opens with Anonymous Sources, which in spite of its unavoidability in investigative reporting, has been greatly abused. The article challenges reporters to always state why a source could not be disclosed in a report. There is however a typographic error—the only one in the book. The FBI is referred to as Federal Bureau of Information. Printer’s devil!

Lanre does not like it when reporters turn themselves into publicists. He examines this in Journalist as Publicist. He mentions names and the issues involved. He comes raw. No ambiguities!

Still under ethics, The Punch and the Rest of Us recalls an avoidable face-off between a former editor of the newspaper and his boss. The author concludes that if taken on face value, the accusations by the former editor, Steve Ayorinde, only confirms that in journalism, all have sinned and come short of the glory of the profession. True?

While reviewing a certain report by Sahara Reporters that Ibrahim Babangida gave editors 10 million naira each after a press briefing, Lanre states that in journalism, the strange is fast becoming the accepted. Absolutely! Even when Sahara Reporters later discovered its unpardonable error, it kept a straight face instead of apologising.

All the same, the author asserts that too many people are in journalism for the wrong reasons, but that with more emphasis on ethical journalism, it would be easy to flush out “the Judas in every dozen.” His conclusion: while on assignment, any monetary gift in the name of or disguised as transport reimbursement “compromises the integrity of the news.” Agreed!

The Media as Culprits is a hard bite on the profession. Every reporter ought to read this. The author, while analysing the journey of Nigeria at 50, is of the opinion that the failure of Nigeria or the political leadership would never occur without the media as culprits.

Wait a minute! If you are the editor of a newspaper and your publisher is arrested, tried and convicted, will that be news to you and will the news find space in your paper? This is examined in a brilliant examination of the conviction of a former bank chief, Mrs Cecilia Ibru—a news item ignored by the Guardian, which she is a co-owner.

Lanre’s conclusion, based on a re-examination of what news is, is quite illuminating. He writes that news is what the news medium says it is. Based on this, he wants us to “imagine if the Guardian were the only news organ around,” then the case “would have been no news—unreported, unavailable to future scholars researching that era of Nigerian life; blissfully consigned to the realm of oral history of dubious veracity.”

This argument continues in He Who Pays the Piper…, which focuses on the refusal of the Nation newspaper to publish a column by Mohammed Haruna because it contained assumed unfavourable comments on its publisher, Bola Tinubu.

After a detailed analysis of what could have influenced the newspaper’s decision to spike the column, Lanre believes that not much harm would have been done if the Nation published the column but that the newspaper chose to err on the side of caution to avoid singing a different tune from that of its publisher.

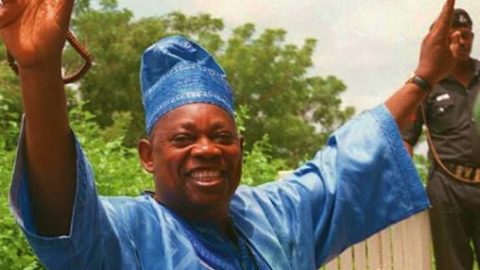

Reading and chuckling is how I can describe my mood as I savour the article on Bode George’s Noisy Return after a prison term. Good prose flows smoothly through the intellect. As you read, you feel as though someone is rubbing your aching back with a balm. The style is exciting, with a satisfying depth of analysis and audacious conclusions.

Lanre is among the grand advocates of making the media more accountable to the people than it is the case now. He captures his thoughts in The Press and Its Code of Ethics where he states that for news to be useful to the consumer, it must represent the best effort of the medium.

Such news must be well-investigated, well-processed and well-served. The conversation continues in two well-researched articles entitled: Guarding the Guards and A Dangerous Bill.

This book does not see journalism as just another job, but a constitutional obligation to the public. Viewed from this background, it is understandable why Lanre has always been all out for ethical regulation of the practice of journalism.

You still remember that “steamy and peppery” newspaper called News of the World? At its peak, the newspaper was known to have circulated eight million copies per edition. Its collapse and what it stood for in its 168 years lifespan is thoroughly and breathtakingly summarised by the author

Lanre narrates some aspects of “conscienceless journalism” practised by the paper. An instance is how it exploited the misfortune of a kidnap victim to make huge commercial success for itself; unmindful of the emotional pain it inflicted on the victim’s family.

Then the sales crashed from eight million copies per edition to less than three million. The next impact of that “deceit journalism” was mass withdrawal of advertising and sales patronage. The paper had no choice but to shut down in disgrace. Shame!

The question arising from the shameful story of News of the World is: how far should the media go? The question naturally brings up the issue of ethics and regulation—who should regulate the media? Do we leave it for government or should it be handled internally by media owners—or both?

From the brazen assault on public conscience type of journalism by the defunct News of World, Lanre brings us back to our backyard where he described the 2014 media coverage of the abduction of 276 girls by Boko Haram as unimpressive because the Nigerian media, “like the Nigerian presidency,” refused to visit Chibok community.

His opinion is that Nigerian journalists seem to have sworn to journalism of convenience; not knowing that journalism is so central to human existence that information that will make that existence worthwhile must be brought to public attention through constructive reporting. Every journalist must understand that people want information and must go for it—the risk notwithstanding.

Don’t Blame It on the Name recaptures media reportage of the 2010 public face-off between the Deji of Akure and his estranged wife, Bolanle. The author states that the press failed woefully in deepening public understanding of the royal disgrace by not answering the question: why did the king visit his estranged wife? Instead, they offered the public what generally amounted to pedestrian reporting.

The article: Privileged Access is a direct opposite of the previous one in terms of style and balance. It is a story of how four journalists and a driver were kidnapped in Abia State. For the first time in the book, Lanre commends the media for factual, emotional and constructive reportage of a public issue.

Reporting tragedies has never been easy because reporters are hardly there when they occur. So, they rely on eye witnesses accounts, which are, in most cases, well coloured depending on who is telling the story. Bloody Sunday is a blow-by-blow examination of how an accident at a police checkpoint in Lagos was reported differently by four prominent newspapers. So much to learn!

An article: Headlines As Micro-Stories is more like a lecture on headline writing. Headlines cast by four newspapers on the same subject matter are examined by the author. Analysis shows that one was factual, the other was attractive, and the third was misleading while the fourth was alarming. Then he goes historical on the trouble with headlines. Insightful!

The passage of the Freedom of Information law is celebrated by the author as a bold move by President Jonathan “to do the needful when all seems hopeless.” In the next chapter, he analyzes the challenges in the new law but however concludes that FOI law can be put into fruitful operation.

In The Media and Daniel’s Daredevilry, the author examines avoidable shortcomings even in the use of pictures in the media. The same critical approach is extended to a report on Stella Oduah’s Select Media Meeting, The Ressurrection of Yar’Adua and Mission to Jeddah.

He spares nobody while discussing the deteriorating health of former President Yar’Adua. The author comes down pretty hard on those in power who did a lot of harm “to our symbol of statehood and or national psyche” by appropriating the ailing president as a personal property instead of a national treasure.

Lanre applies a truckload of sarcasm to announce Ibrahim Babangida’s return to politics in the next chapter. But it is the unfortunate death of Yar’Adua that presents him opportunity to recapture in a movie-like script how and what the late president went through in the hands of his minders who blocked the nation from knowing what was happening to their president.

President Goodluck Jonathan is featured next as the author raises issues in Thisday’s and Tell magazine’s intimate account of Jonathan’s family, which ended on a controversial note on whether the president has two children (Thisday) or three (Tell).

The Media and Anambra Election attracts Lanre’s attention next. With 25 contestants for one office, he states that media access depended on the size of the aspirants’ purse and not richness of ideas. Conclusion: if the election succeeds, “most of the credit should not go to the media.” Another slap!

Zoning, ethnicity and religion as considerations for election to public office cannot be easily dismissed in the political history of Nigeria. The author examines this before cautiously jumping to another mind-blowing piece of literature entitled: Of Political and Journalistic Rascality. He states: “Nigerian media has no sense of humour. What a piece!

SAM AKPE …is our CONSULTING REVIEW EDITOR.

TO BE CONTINUED IN PART 2