BY SAM AKPE

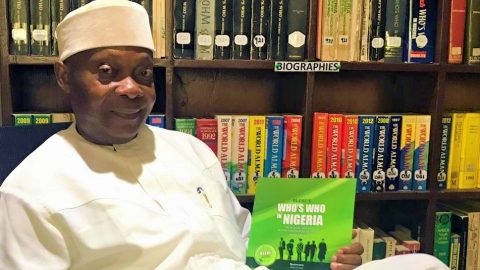

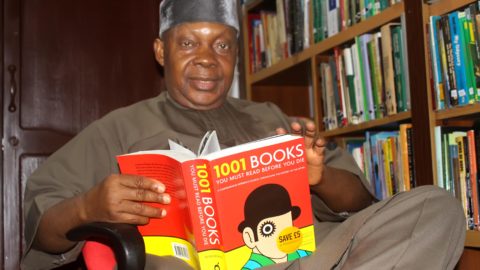

Oh my God! Here is the book at last. It is not meant just to be read; it is to be studied, enjoyed and applied. As you ponder over each sentence that flows into loaded paragraphs, practical knowledge keeps oozing into your brain. What makes the book so important? Simple! It is written by Ndaeyo Uko.

Story Building: Narrative Techniques for News and Feature Writers is Ndaeyo’s latest intellectual contribution to journalism. Someone may ask, how do you build a story? This book tells you how and why. It compares story writing to a building; and discusses all the requirements; from architectural plan to site arrangement, laying the foundation, doing the block work, the roofing and the finishing. Each chapter, each paragraph and each sentence makes you wonder why it took so long for Ndaeyo to write the book. But, here it is, finally.

The book simply answers the question: how do you tell a story such that the reader feels mentally trapped in the beauty of factual details and savour the reward of the tale? Such satisfaction is only derived from the narrative approach to news and feature writing as against the traditional 5Ws and H. This is why the author believes that no news is hard news; meaning that, “a story is a story whether it comes in the form of news, feature, review or opinion.” I can sense my journalism teachers clearing their throats and shaking their heads; slowly.

In the 21st century journalism, the good old inverted pyramid news presentation style seems to have outlived its usefulness. If it has not died yet, but it seems to be in coma. Inverted pyramid has become “anti-story” because while it simply highlights the main fact of the story, the narrative interprets the meaning and significance of the story. It adds and explains the drama without failing to personalise experiences.

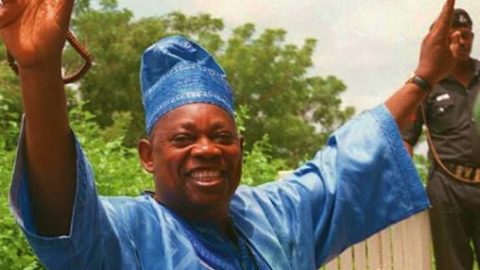

Wait a second! Ndaeyo has never been without controversy both in what he writes and mainly how he writes. He caused a stir in 2002 at the 23rd Annual Conference of the Australia and New Zealand Communication Association when he presented a paper with a shocking declaration: Hard News is No News in the 21st Century. The paper argued that the days of the old school—inverted pyramid—news presentation format are over; “and that all news, hard or soft, will have to be featurised.”

Ndaeyo is not new to writing or proposing unconventional ideas. So, you don’t need to bang your head against the wall because the book: Story Building: Narrative Techniques for News and Feature Writers, says narrative is not limited to features and some other long haul stories but also serves breaking news. What this means is that a reporter should look beyond the hard news and supply the reader a richer reading experience using perceptions, styles and such techniques as humour, grace and irony without sacrificing meaning, immediacy and public interest.

This basically implies that good journalism writing should go beyond pre-set structure (5Ws & H) and focus on the content. Simply put, good journalism writing should recognise content over shape. It must be based on sound reporting; which means being insightful and compelling—with illuminating details.

The book reveals that narrative reporters daily provide a mental picture of the world. They piece several actions into a coherent, meaningful and memorable account that excites the senses of the readers. They cause the reader to “see, smell, touch, feel and hear” events unfolding either far away or nearby. This is not about colourful words but precise and concrete actions expressed through strong nouns and verbs. The book makes suggestions for narrative reporting. It examines reactive, perspective, and reflective reporting.

One of the chapters is entitled: Finding the Shoehorn: Aggressive Observation. Here, the author presents the Chucky Test. Shoehorn—as used here—refers to invisible details observed only by trained eyes. A story is as rich as the reporter makes it. Sometimes, what may pass as insignificant detail may contain “powerful symbolisms” that would fill the gap, add vitality, human drama, reveal precise information and make the invisible visible in the story. These are ingredients of great narratives.

So, as reporters, what do we observe? When you observe the atmosphere, you will notice the shape of the event, the colour, the dimensions, the texture, the movements, the condition, and the mood. The author explains each of these with examples before progressing to the next two chapters which focus on interviews.

The discussion on interviews reveals a lot more about Ndaeyo and his ingenious writing style. With examples beyond his personal exploits in journalism, he brings back the living words of Nora Villagram who once said that in seeking interviews, “if the front door is locked, try the back door; if the back door is locked, try the window.” That means, be persistent. Don’t give up. At the same time, be sensitive to the feelings of the subject and the interest of your story.

The abuse and use of descriptive detail attracts the attention of the author in the next chapter. For a strong story, every journalist must learn to eliminate useless details. While it is allowed for the reporter to gather all the details out there at the beat, he must learn and master the art of “judicious selection of details (because) it promotes trust between the reader and the writer.”

What is proposed in the book is selective use of details in a story. As much as descriptive details are vital to good writing, it is recommended that great reports should separate gold from debris, wheat from chaff and sense from nonsense. Descriptive details should only be used to “promote a deeper understanding,” but not in a way that they constitute “an obstacle, a distraction or a decoration.” To avoid this, every writer should combine the excitement of freedom of perception with the discipline of selectiveness.

The unwritten rule is this: in reporting, observe every detail so that you will have a wide range of materials to select from. Understand that in journalistic writing, concrete description sets the scene and reveals ironies and symbolisms. Use descriptive detail not to adorn but to energise the story because “focused and illuminating description draws in the reader.” Ndaeyo believes that every good writer must always think and write for the reader. Only bad writers pour heaps of “pointless details on a story to display their descriptive prowess.”

Descriptive details perform specific functions in story. But when they fail to enhance understanding of the story and the event; or heighten the pleasure of reading by putting the reader right on the scene; or move the story forward; and help in smooth transition, then they become noise. Most importantly, descriptive details must be factual and not merely decorative. Journalists are not expected to use descriptive details to impress the reader. It should tell a story.

Style, states Ndaeyo, defines who the writer is – how he thinks; how he sees life; what he reads and perhaps, where he has been. Style defines how a reporter does his job in terms of the “unique selection and combination of words.” Keep it simple. Show more action than tale. Use short sentences. The book contains examples of the worst and the best styles. Every writer ought to be mindful of the truth that good writing involves one’s “ability to use ordinary words in an extraordinary way.”

Every story, just as a building, has a design. It is such a design that helps in arrangement of factual details and removal of extraneous ones. Story design is not the final blueprint of the story. Story design helps establish focus, specific goals and destination. Principally, story design, which could be a mental conception, gives the narrative a structure and takes away digression. Story design helps in smooth transition—a writing element described by the author as the inner engine of a story. Transition is achieved through thorough “arrangement of information and details;” such that a sentence merges into sentences and a paragraph merges into paragraphs “to produce a coherent story.”

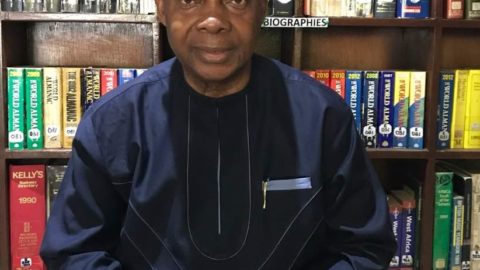

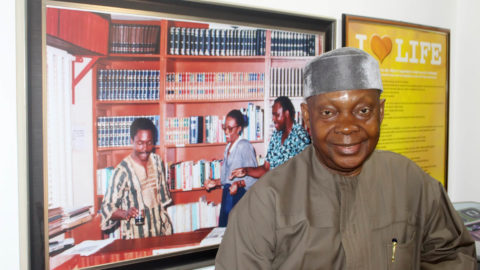

This book is not just a text that propagates inspiring approaches to news and feature writing. It is a product of years of journalism practice across three continents. Ndaeyo is not presenting a theory yet to be proven or put to use. He theorises what he has practiced over the years as a reporter, editor, and journalism teacher. He has reported and even edited some of the most influential national newspapers in Nigeria. They include the Daily Times, the Punch, the defunct Post Express and the Guardian. Outside Nigeria, he has reported and written for the San Jose Mercury News, and the Daily News in the United States of America. In the United Kingdom, he has written for the Independent, the Guardian and the West Africa magazine. Ndaeyo was at the University of the Virgin Islands where he ran a journalism programme. He currently teaches journalism at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia.

So, studying this book is made more thrilling because Ndaeyo writes from the perspective of practical experience devoid of theoretical pontificating. He writes about what he has done, not only what ought to be done. The book is filled with practical or on-the-job examples. What Ndaeyo states in the book is not mere scholarly discourse but practical wisdom flowing from years of experience on the beat; in the newsroom; and in the classroom.

The book therefore is a product of reporting and teaching experiences. Each chapter takes you back to your beat; reminding you of what detail to look for so that the story will flow effortlessly; and richly too. Most importantly, it reminds you of what your readers expect. That realisation is expected to practically sharpen your professional instinct as an observer of events.

Ndaeyo discusses every aspect of news writing. For instance, even in narrative writing, he says the lead, as well as the body and the ending of the story, is paramount. There is what is described as an arresting lead that combines organic structure, vivid imagery and captivating quotations meant to establish a powerful ending. Again, it is an unwritten rule that the lead should entice the unsuspecting reader; connect him to the writer; and lead him by the hand into the story.

The lead of a story is compared to the foundation of a building. It determines the strength and the slant of the story. The writer uses the lead to earn the trust of the reader because from the lead, he is sensitive to the appetite of the reader. While there is no standard ingredient for a lead, Ndaeyo states that often, contrast, conflict, irony, paradox and other humanising details would do.

Journalism practitioners will discover through this book that an opinion article does not imply the opinion of the writer. Readers are more interested in getting enlightened by the ability of the opinion writer to factually analyse issues and not download his beliefs and biases on them. Opinion articles are about collection and analysis of facts in a refreshing and unique way that persuades, educate the reader, and even further the debate.

Ndaeyo implores opinion writers to build the body of their article with quotations, anecdotes, illustrations, scene and images. The ending, of course should present the reason behind the article; sum up the argument presented in the piece; and not a personal point of view.

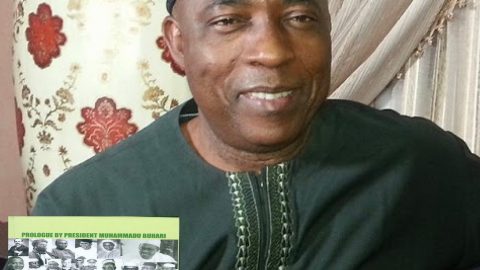

Produced with tiny font, the 234 page book is not Ndaeyo’s first. Before leaving Nigeria to practice, school and teach abroad, Ndaeyo had, in 1992, written The Rock ‘N’ Rule Years: A Satirist View of Nigeria’s Military Presidency. The book actually rocked and ruled the intellect for a long time. It was described by one reader as an “exceptionally witty, funny (book) by a wickedly intelligent author.” Another book, Romancing the Gun: The Press as Promoter of Military Rule, was published in 2004. It was an unusual book that drew silent flaks even from professional colleagues.

So, if you find yourself not agreeing with all the revolutionary ideas discussed in this book—complete with practical examples—it may just be because Ndaeyo is just who he is—someone who does not do the usual. Even his neck-tie is permanently at half-mast.