BY OBOT EMMANUEL OBOT, Ph.D

A Review BY SAM AKPE

Close your eyes for a moment. Take a deep breath. Imagine this: a couple waited several years to have a child. They prayed. They fasted. They went through complicated medical tests. Then comes their long expected dream, a baby—a boy. Few days after birth, as the tradition is, the boy is due for routine circumcision—a medical procedure that requires no specialty. Then the unthinkable happens. In the course of performing the minor surgery, the boy’s penis is cut off at the base by the doctor. Nothing is left of it. The poor boy starts to yell as he bleeds uncontrollably. What will you do if you were the parents of the victim?

What about the case of a bubbling young man diagnosed of appendicitis—inflammation of the vermiform appendix. He goes to a hospital and meets with a doctor who prepares him for immediate surgery. However, after the surgery and a discharge from hospital, he suddenly starts feeling a persistent different kind of pain as days graduate into weeks. He consults another doctor who quickly senses that something is wrong. The patient is immediately subjected to a scan. Behold, inside the very spot where the appendix was removed, a pair of surgical scissors and surgical glove are found competing for space. Who put them there and what are the consequences?

One more bizarre instance: An accident injury has rendered one of your friend’s legs useless and is due for amputation based on the advice of an orthopaedic surgeon. With preliminary medical processes completed, your friend is stretched out in the theatre ready for the surgery. The orthopaedic surgeon—the same person that recommended the surgery—is in charge of the procedure. At the end, what would have been a successful medical exercise turned to nightmare as it is discovered that the surgeon has cut off the only functional leg instead of the one affected by the accident. Where does that leave the patient?

The list is endless. Horrible stories of medical negligence. They equally include situations where a greedy and unguardedly ambitious general practitioner decides to perform complicated surgical procedures which he is not qualified to perform instead of referring the patient to specialists who are well versed in such procedures. The result could be permanent incapacitation or death of the patients. These incidents are true reflections of what patients in different countries of the world have passed through in the hands of medical doctors. Some of the patients live to tell the tales; others die and have the tales told about them.

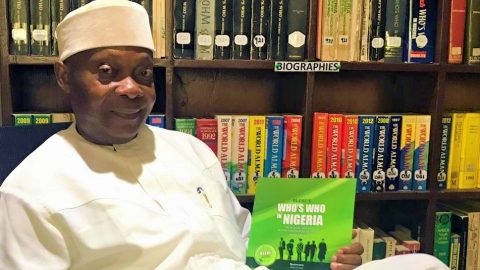

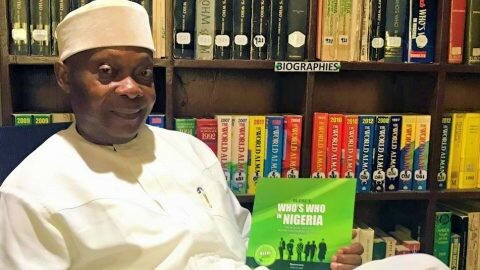

Faced with above situations, what should the patient or relatives of the victim do? What does the law say? These questions are answered in the book entitled: The Snake Is In Court: Bringing A Lawsuit Against A Doctor For Medical Negligence; written by a lawyer, Obot Emmanuel Obot. The Foreword is written by two renowned professors of medicine—a paediatrician (Emmanuel Ekanem) and a forensic pathologist (Martin Nnoli). The book educates the reader not only on what medical negligence is but on what the law says about such negligence and how to seek redress in court.

Truth sometimes is not only bitter but equally controversial. This book possesses those two qualities. It is not only factual but a truthful account of inexplicable pains sick people and their relatives go through in the hands of medical practitioners. Something tells me it is going to be a controversial piece of literature loved by the majority and hated by a few others—but read by both. It will put fear-of-the-unknown in the patients and fear of full disclosure and the legal consequences in doctors.

The book states without any ambiguity that when issues of medical negligence arise, the conduct or actions of the medical practitioner involved are weighed against the level of competency and professionalism which qualified practitioners would have exhibited when faced with the same situation. This implies that a general medical practitioner who goes into areas of medical practice that is beyond his competence will—before the law—be judged by the standard of specialty in which he tried to act.

Obot however draws a line between medical negligence and patient’s dissatisfaction with the result of medical care. Medical negligence involves situations where the patient suffers real avoidable harm caused by sub-standard level of medical care—a situation that would have been avoided if the practitioner had exercised required competence in the process of treatment.

Written in a fast-paced, simple but elegant prose—with medical and legal jargons meticulously defined and explained—this book has been long time coming. If you have been sick enough to require medical attention or you have heard of someone in that condition, this book should interest you. Unlike what we know of lawyers, Obot says so much in few words—the book is only 180 pages. While the author is not economical with the truth, he is very economical with words. The book is lean in size but loaded with relevant hair-raising truths.

From the first page of the narrative to the end, you are likely to be puzzled about the background of the author. The book is heavily historical on the often-ignored origin of snake as the symbol of medical profession. From there, the author moves to the scientific aspect of medicine from the ancient world—with mention of specific countries—up to the 21st Century. Among them are the medical inventions and development from 460 BC when Hippocrates—founder of the first university of medicine—was born, to 2018 when research and breakthroughs in needle-free injections, male birth control and double-face transplant were confirmed. Obot discusses all of these with the ease of a thoroughbred scientist, the excitement of a researcher and the authority of a historian.

By the way, Obot studied economics for a first degree at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Shortly after, he went in pursuit of his passion at the University of Calabar where he studied law; went to the Nigerian Law School before earning a post-graduate (LL.M) degree at the University of Uyo and doctorate degree at Ebonyi State University. With more than 26 years post-call experience in legal practice, Obot heads a legal firm in Akwa Ibom State and has been a law teacher at the University of Uyo.

Obot has written a book only someone with his virtues can—enthusiastic, bold and remarkably authoritative. From the introduction to the epilogue, you are trapped in a breathless assembly of undeniable facts about medicine and law. The research is deep and the revelations are thrilling—even scary. Every example and figure cited in this book is authenticated with proven sources either from books or medical journals.

The central theme of this uncommon literature is to boldly expose—without any damage to the profession—the wrong doings of medical doctors committed in the exclusive safety of consulting rooms and operating theatres. Although such wrong doings cover every medical professional, the book focuses on medical doctors whose mistakes have often brought pains and death to patients. While “stimulating public awareness on what medical negligence is,” the author also creates pathways of legal processes which those who suffer medical negligence can follow in search of redress.

The Snake Is In Court: Bringing A Lawsuit Against A Doctor For Medical Negligence defines medical negligence as a condition resulting in an act or omission on the part of a health-care provider in which—either due to incompetence or carelessness—the standard of care provided deviates from the “accepted standards of medical practice and causes injury or death to the patient.”

The author states in clear terms that part of medical negligence—and perhaps the most frequent—has always been the decision by certain doctors not to tell patients about the diagnosis, the risks and the foreseeable results of medical treatments. The author, from the position of law, believes that it is the doctor’s duty not only to provide the patient with information about the treatment, but to honestly answer the patient’s questions. He must explain the chances of success and the risk of failure of suggested treatment.

It is the informed position of the scholar that when patients consult doctors, they need to be able to value and trust the judgement of such doctors. This includes ability to interpret complex information, support the patient in understanding their conditions and what to expect and discuss risks. Obot believes that only a well-informed patient is in a position to make “free and informed decisions with full knowledge about the facts of the treatment and the care offered.”

Chapter Four of the book deals with understanding medical negligence. Here, Obot takes the reader into the different meanings of the key word: negligence. Consulting several dictionaries and legal authorities, he, not only explains the different meanings of the word, but also the fragile semantic distinctions between neglect and negligence. Perhaps, most illuminating is the Black’s Law Dictionary definition of negligence as “the failure to exercise the standard of care that a reasonable prudent person would have exercised in a similar situation; any conduct that falls below the legal standard established to protect others against unreasonable risk of harm, except for conduct that is intentionally, wantonly, or wilfully disregarded of other’s rights.”

A sub-heading: the concept of the reasonable person in the law of negligence comes with thrilling revelations. Citing certain court rulings, the book reveals that for the tort of negligence to be actionable, the defendant must owe a duty to the plaintiff; that duty of care must be breached; and the plaintiff must have suffered damages arising from the breach.

The conclusion is that negligence, in the eyes of the law or the court, is more than a mere heedless or careless conduct whether in omission or commission. It means failure to take reasonable care where there is a duty and is attributable to a person whose failure to do that has resulted in damage to another. It is the failure to do something which another reasonable man under similar circumstances would have done.

Another beautiful distinction drawn by the author here is between medical negligence and medical malpractice. Examples of medical negligence listed include delayed diagnosis, misdiagnosis, anaesthesia errors, medication errors, surgical mistakes, among others. He goes ahead to list and explain nine revealing areas in medical practice considered in legal circles to constitute professional negligence.

Every medical doctor, states the learned author, is expected to exercise what is called standard of care. This describes a degree of knowledge and skill, care and judgement which other medical doctors in same or similar situations and localities usually exercise under similar circumstances. References are made to the 1942 Geneva Declaration and the International Code of Medical Ethics. Historic legal rulings are also cited.

In suing a doctor for medical negligence, the patient or relatives also enjoy what is called vicarious liability in which a hospital where the doctor committed medical negligence is equally held responsible for the offence. In fact, the author, from the position of law, reveals that where a hospital provides sub-standard equipment for use by doctors, thus resulting in incapacitation or death of the patient, the hospital equally has a primary liability for negligence. Did I hear somebody ask whether government can be taken to court for under-equipping its hospitals—a situation that has led to death of patients? Why not, as long as you can present proofs of damages.

Wait a minute! Have you ever noticed that medical doctors write prescriptions and medical reports in a manner that others cannot read? Unknown to the public, such ineligible handwriting has often led to medication errors by pharmacists and other healthcare officials. Obot reveals in Chapter Five that a doctor’s handwriting can mean the difference between life and death for patients. In fact, research shows that 7000 patients die yearly due to doctor’s sloppy handwriting. That on its own is medical negligence. The victim can sue and claim damages if he is alive to do so. The author lists and explains four broad types of medication errors which include: knowledge-based errors; rule-based errors; action-based errors and memory-based errors. The fifth is the technical-based errors which include ineligible handwriting that could be misinterpreted.

Writing a highly technical book about two complicated, unrelated issues in simple, understandable style by a scholar in the class of Dr Obot is unusual. The book explains that wrong diagnosis resulting in wrong prescription is the chief cause of wrong medical treatment. For women in labour or after birth, nine types of treatment failure categorised as medical negligence are listed in this chapter. You don’t want to miss that.

Hold it! Take a deep breath because this is going to shock you. The book reveals that every year across several hospitals, no fewer than 4000 items are unintentionally left behind inside patients’ bodies after surgeries. These have resulted in various types of afflictions and death of patients. This happens when doctors do not take inventory of equipment and items used in the theatre before and after surgery.

One fascinating aspect of The Snake Is In Court: Bringing A Lawsuit Against A Doctor For Medical Negligence is that every area of medical negligence discussed is backed with either existing statutes covering the practice or court judgements on similar issues in and out of Nigeria. Unfortunately most patients and victims of medical negligence in Nigeria are ignorant of the existence of such laws.

In a multi-religious country such as Nigeria, what happens to a patient’s right to withhold consent and refuse medical treatment on religious grounds? Does a doctor also have any right—based on religion, nationality, race, party, politics or social status—to refuse treatment of patients? These questions are exhaustively answered in Chapter Five of the book drawing from existing legal guidelines and courts rulings.

Two crucial sub-topics end the discourse in Chapter Five. The first is failure by certain doctors to refer patients to specialists. This happens when a patient has complex problem that is above the primary care of the doctor. The author states that such a doctor has the legal and moral obligations to refer the patient to someone with more skill and competence in that area.

The second discussion is on breach of confidentiality. It is the author’s position that patients’ disclosures to a doctor must be kept confidential except if the information is permitted by law for public interest, or the information is needed in court based on court order, or the patient voluntarily consents to its disclosure.

The last chapter of this engaging book dwells on legal options for claims and redress for medical negligence. It states the position of the professional medical body, the criminal prosecution approach, the civil litigation approach, and proof of the legal elements. The reader will find these discussions extra helpful because it states in clear terms what victims of medical negligence need to know—the step by step approach of establishing that negligence has been committed. The author discusses duty of medical care under law, what constitutes breach of medical care, and the causation—a proof that the doctor’s negligence caused the injury. Obot states that despite obvious breach in duty of medical care, the patient must prove, on the balance of probabilities, that the doctor’s poor performance caused the unsatisfactory results.

Proving medical negligence is quite an interesting narrative. When you study this book, it becomes clear why many Nigerians hardly pursue redress in cases of medical negligence. The process is full of roadblocks. From getting the medical report, to finding independent medical experts to interpret whether negligence was involved and being ready to testify in court, are steps the plaintiff must be prepared for. This chapter is categorical that “where the patient died as a result of the doctor’s negligence, the surviving relatives can bring an action for compensation in respect of funeral expenses and damages for loss of dependency and services as well as for cost of action.”

Before you read the appendix, take a deep breath again and be prepared for multiple shocks. This part of the book chronicles some horrible medical negligence cases across the world. They include cases where a doctor performed brain surgery on the wrong person, surgery on kidney instead of gallbladder, surgery on kidney instead of removing a tumour, among others.

This book does not seek to pass blames. It simply tells the truth in a two-sided manner. While exposing the foul practices, which are products of carelessness and greed on the side of health care givers, the book has not only subtly exposed the ignorance but equally educates the health care consumers on their rights under the law. Few doctors—if any—can claim to have done it perfectly every time; and few patients have been spared the agony of medical negligence—no matter how negligible.

Obot ends the book on an evangelical note. He introduces the reader to someone who has never made a mistake in the cause of conducting healing procedures. This is how he captures it: “There is a doctor in whose practice there is no negligence, no malpractice and no fees charged. His name is Jesus. He is the master physician and in His practice nothing is impossible. Where Jesus displays His healing power, death and curses are known no more. In Him, the tribes of Abraham boast. Call on Him now with faith.”

Clearly, without a book such as The Snake Is In Court: Bringing A Lawsuit Against A Doctor For Medical Negligence, sick people who seek medical treatment in public or private hospitals would be ignorantly sentenced to long suffering and avoidable death in the hands of medical doctors who are either incompetent or are insensitive to the details of their calling. But with these revelations, we all know our rights in any worse case scenario.

This book will open the inner eyes of every unbiased reader—both the health care givers and the consumers of health care services. As revealed by Obot, it does not take a complicated surgery to be a victim of medical negligence. It takes carelessness, unguarded presumptions and sometimes, outright incompetence on the part of the health giver—the medical doctor.

END