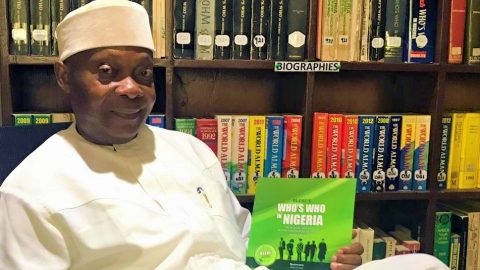

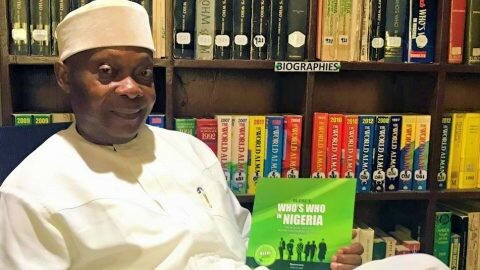

BOOK REVIEW BY SAM AKPE

Here is the book, finally: Clement Nyong Isong: A Life of Integrity, Discipline and Public Service. It is the biography of one of Nigeria’s silent but great patriots. Surely, and without doubt, it’s been a long time coming. Many wished it would be written. Good enough, it has now been written. From the first page to the last, each sentence is a walk into the past and a glance at the future. You keep wondering: how on earth did he make it to the top under the circumstances he faced? As you lift your head to ponder over this, with your eyes pointing ahead, there is that imaginary voice—some kind of a reminder—that he did all of these to inspire us against giving up—and cause us to run and not just walk lackadaisically with our vision.

In the words of Dr Yakubu Gowon, his former boss, Dr Clement Nyong Isong was a man driven by a powerful sense of duty and mission. This drive made him to surmount powerful obstacles and tribulations while in pursuit of his dreams. He was born into a poor family—a family that lost about half a dozen of his siblings before he arrived to end the jinx. Nobody—not even his parents—thought he would survive. They gave him the name Nyong—a deep Ibibio expression meaning a wanderer. It was just one of such names wrapped in uncertainty and meant to mock his birth so as to avoid another death. Others were Nkamiang, meaning the cunning one; Ekpo, meaning ghost or ancestral spirit; and Ekpeyio, meaning the one who moves around.

Yet, he lived. In fact, his birth on April 20, 1920 was followed in quick succession by the birth of two other female children, Alice and May. They too, lived. His father, Nathaniel Isonguyo Ekpa Ebai Ito was from Ikot Osong while his mother, Maggie, was from Ikot Akpan Ntebon, all in modern day Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. His father died while Isong was in Infant Class 11. As the tradition was in those days, Isong’s mother had to marry one of the relations of her late husband. So, if Isong was born into a poor family, in his early years, he virtually grew up with poverty as a roommate.

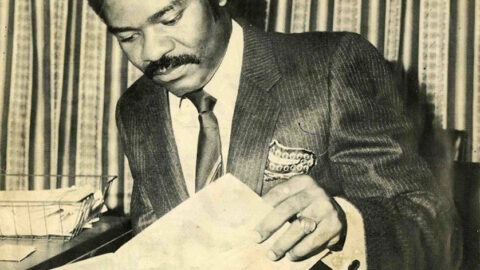

One day, many years ago, I had an opportunity of an interview with Dr Isong. Sweet memories! The interview was not mine. In fact, I was a privileged apprentice-journalist in company of my former teacher and a veteran reporter—Parchi Umoh—who was then an editor with the Champion newspapers. Isong looked into my face with those dark penetrating eyes as he responded to one question I had the audacity to utter: It was about his unfulfilled dreams. His response: No unfulfilled dream. His passion was to always be a man in charge. And this, he did. He became a banker—in charge of the nation’s money; he became a teacher—in charge of people’s intellectual growth; and he became a political leader—commanding obedient followership from millions of people. He accomplished all his dreams; at the highest levels possible.

The 363-page book, Clement Nyong Isong: A Life of Integrity, Discipline and Public Service starts with the story of Isong’s birth and the travails of his parents which rubbed-off heavily on him. His mother, Maggie, is described as a symbol of hard work and resilience. For instance, she was married to three husbands at different times. Maggie was a trader, a farmer and a church treasurer. At a time when the highest anyone dreamt of in the village was Standard Six education, she had tall dreams for her children, mostly the boy who broke the spell of infant mortality in her life.

Growing up, Isong was not permanently diseased; but his health condition was not fantastic either. At a point, his parents took him to a famed native doctor called Ataotoro. Instead of treating the young man, the native doctor turned him into a fisherman. Yes, Isong started life as a fisherman. At a certain point he was on the high sea for two weeks; fishing. When he finally stopped fishing, Isong became a houseboy; he combined this with petty trading in cigarettes—in a bid to augment his mother’s meagre income. Then he became a teacher in 1939 after completing his teachers training education. His salary in 1940 was £42 a year. Isong later became a lay preacher while teaching at Methodist Boys High School, Oron.

The book captures in detail Isong’s admission to the University College, Ibadan in 1949 for a diploma programme in education. The one-year experience opened his eyes to greater possibilities. The author, in Chapter Two, narrates in an interesting manner how little Isong dreamt of, and eventually gained admission to Iowa Wesleyan College on a scholarship. On the day he left Nigeria for US, his people scooped some sand from his home ground, wrapped and gave him. This was to serve as a reminder that he must return home after his education; and he must not get lost in the traditions of the white man. At Iowa, he set a record and was later described by the school as being among “the most outstanding African students to have come to the United States…”

Then began Isong’s search for a wife—a story of courage, perseverance and adventure. He got a wife who turned out to be just who he needed by his side as he pursued his dreams. That, however, did not come easy.

Before marriage, Isong’s desire to get admitted to Harvard for post-graduate studies is a narrative full of suspense. Harvard University was established in 1632. Isong was admitted on December 16, 1953 to study economics with emphasis on public administration. He was on the colonial government’s scholarship. He completed the programme in June 1955 and immediately applied to study for a PhD in economics, which he completed in June 1957. With this, change came dramatically to the village boy—but not on a platter of gold.

One of the attractions of this book is the depth of research carried out by the author. By the way, Adesina is a professor of history at the University of Ibadan. He had his PhD at Ife and has twice headed the History Department at Ibadan. A fellow of Atlantic History, Charles Warren Centre at Harvard University, Adesina is equally Visiting Fellow, Rhodes Chair of Race Relations, St Anthony’s College, Oxford University; and Fellow of the Institute of Advanced Studies, Jawaharlal University, New Delhi, India. Author of many books, Adesina’s background as a historian adds extra value to the book. He approaches every aspect of the story with the mindset of a historian.

After a stint at the Federal Reserve Bank in the US, Isong returned to Nigeria and taught for about a year at the University of Ibadan. The book details the process that led to the establishment of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) which began operations on July 1, 1959. Two foreigners, Roy Pentelow Fenton and G. W. Keep, were appointed governor and deputy governor of the bank, respectively. Isong was appointed the pioneer Secretary of CBN. One of his responsibilities was to recruit qualified indigenous staff to manage the bank. Curiously, when the two expatriates left and it was time for Isong to step in as CBN Governor, ethnic politics set in. Isong was by-passed. People he recruited and trained became his bosses. Isong was instead sent to the IMF as adviser in the Africa Department. Good riddance! Or so they thought.

However, that was not the end of the dreamer—and also not the end of ethnic intrigues. When the two top Nigerian officers of the bank eventually retired in 1967, the British Government was contacted by the Federal Ministry of Finance to send someone on temporary secondment. The colonial government baulked at the idea. As if for lack of any alternative, Isong was on August 5, 1967 appointed to head the CBN. He assumed duties 10 days later amidst protest by the same colonial government over his strong American connections—a PhD from Harvard and five working years in Washington DC.

Managing the CBN—and by extension, the Nigerian economy—during war time constitutes in part, the main focus of this book. The author weaves a story of inhuman challenges that greatly tasked the intellectual and patriotic capacity of the war-time CBN governor. Isong presided over the change of Nigeria’s currency on January 3, 1968. Reasons for the change are well explained in the book. One of the significant events described by the Bank of England as a world record set by Isong was the successful floating and execution of Win-the-War-Bonds by the CBN. The book reveals that despite the war, the Nigerian economy was in good health with increase in establishment of commercial banks across the country from five in 1960 to 14 in 1970 with 273 branches and with phenomenal increases in asset base.

Chapter Five of the book dwells on post-war reconstruction and what the author refers to as the limits of power. It presents Isong as a frugal person—not just regarding spending on his family but as chief financial manager of the war-torn country. One day, Isong called Yakubu Gowon, the military leader; got an appointment and went to Dodan Barracks to see him with one message: the economy is extra healthy with excess foreign exchange earnings, what shall we do with the money? This gave rise to the most repeated and (mis)quoted statement: “money is not our problem but how to spend it.” The book reveals a fast-growing post-war economy under Isong that equated N1 with $1.60.

Despite his near-wizardry in financial management, Isong—through a military fiat—lost his job on September 22, 1975. He left the CBN with his head held high. Then came life after the CBN. After a brief stop-over in consultancy business, politics showed up. The author paints a word picture of how Dr Isong got involved in politics of the then Cross River State. It is a beautiful narrative that reveals the reluctance of one man against the unrelenting persuasion or never-give-up spirit of a community of like-minded people. He was eventually drafted. On October 1, 1979, at exactly 12.35 p.m., he took the oath of office as the first elected governor of Cross River.

Politics, power and the people forms the discussion in Chapter Seven. A peep into Dr Isong’s family also makes up a part of this chapter. As governor’s wife, Nne Isong was still working and earning a salary in Lagos until an incident forced her to join the husband in Calabar. Soon the cracks appeared on the walls of his administration when he refused to play politics of stomach infrastructure with state funds. Those who had persuaded him to join politics led the campaign against his second term.

Quite difficult to understand was the fact that those opposed to his second term bid, referred to as the Lagos Front—were members of his party—the National Party of Nigeria. It was led by Joseph Wayas—the then Senate President. The author, in capturing this scenario, states that there were indeed: “A multitude of barriers erected on the path of the Isong administration from within the ruling party; to discredit him.” Suddenly, the State House of Assembly served him impeachment notice comprising 13 charges. Dr Isong’s responses are extensively discussed in the book. He justified all the actions and inactions he was accused of and even cited serious violations of procedure by the state legislature. At the end, the House voted 50 against 20 to end further action on the impeachment threat. Seven members were either absent or abstained. Despite this, Isong lost re-nomination bid for second term.

The military coup that followed did not spare Isong and his colleagues. They were all carted into jail where he spent 20 months. His travails in prisons across the country and the suffering by his family are extensively discussed in Chapter Eight. The author narrates that charges against him were drawn from speculations of mysterious arms and ammunitions allegedly found in his residence by policemen. At the end, he knew no freedom even after the court discharged and acquitted him.

Chapter Nine of Clement Nyong Isong: A Life of Integrity, Discipline and Public Service is all about the family Isong raised. The training he subjected the children to, and what they later became, make quite an informed reading. Chapter Ten ends the book with testimonies from close associates. Truthfully, as the author observes, the chronicle of Isong’s personality revealed the incongruous combination of brilliance, fairness and resilience. On May 29, 2000, at age 80, Isong passed on.

In Clement Nyong Isong: A Life of Integrity, Discipline and Public Service, the world witnessed the rise of a petty trader, a lay preacher, a house boy and a fisherman to the apex of his career in banking, academia and politics. He attended one of the best and most expensive universities in the world by a stroke of divine provision. Isong taught the human race a lesson in making the best of every opportunity. This book is not the end of Isong’s story—it has only sharpened the appetite of future authors to further tell the story of a man whose vision could neither be blurred by sickness nor his mission halted by poverty.

Book written By Prof Olutayo C. Adesina