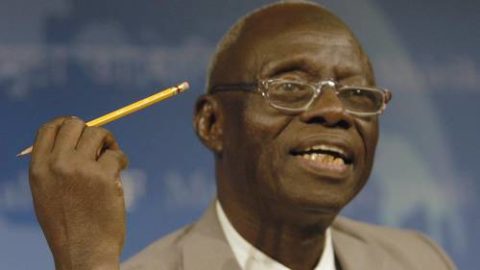

By Stanley Macebuh

I speak as one who claims a spiritual bond with Dele Giwa, as one who, in a certain sense, must

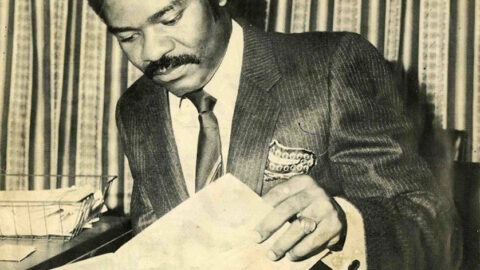

share the guilt of his death. In the winter of 1977, Dele Cole, then the chief executive of the

Daily Times, sent me on a fateful mission to New York. He had heard of a bright young Nigerian

working at the New York Times, and he was determined to bring him home … So my

assignment to New York was a simple one: to ‘bring Dele Giwa home.’

Requiems are, or ought to be for old men. To memorialize a man cut down in his youth is to accept as invetitable what, in truth, is unnatural. And yet, not to do so is to deny that man’s history, to do violence to our own sense of community.

There are men who need three score and ten years to fulfil their life’s mission. And there are those for whom only half that time is sufficient. Dele Giwa needed only that time, and yet the testimony of his brief life haunts and taunts us with unanswerable questions over what more he might have done in another ten years.

I speak as one who claims a spiritual bond with him, as one who, in a certain sense, must share the guilt of his death. In the winter of 1977, Dele Cole, then the chief executive of the Daily Times, sent me on a fateful mission to New York.

He had heard of a bright young Nigerian working at the New York Times, and he was determined to bring him home. I myself had returned home the previous January, beguiled by Dele Cole’s evocations of patriotic duty. My assignment to New York was a simple one: to do to Dele Giwa what Dele Cole had done to me.

We met for lunch on a cold, windy day, and I painted for him a canvass of possibilities. The soldiers were getting ready to return to barracks. The Second Republic was soon to come. The tired old men of the First Republic would, no doubt, follow the soldiers to their hearths, and a new generation of Nigerians had their task cut out for them, to create anew the foundations of a just, democratic society.

In 1977, I believed in these things. It was a question of faith. But Dele Giwa, young as he was, was not impressed. The prospect of a great political revival did not interest him. Politics, he said, was for Charlatans and knaves. What fired his imagination was my reference to a jaded, morbid newspaper called the Daily Times, for which I then worked, and the possibility of transforming it into a living instrument for clobbering politicians and exposing the rottenness they lived in.

He came home, finally, with no illusions, and with a far cleared idea than I myself had of what his personal duty was. Mine was a darker and certainly more tolerant vision of man’s clumsy but inevitable movement towards perfection. Dele had no patience for such sentimentally.

History for him was action, heroic, personal action. He had little faith in institutions, seeing them as a screen, merely, behind which wicked men concealed their vile, inhuman dreams. And everything he did was informed by this faith, passionately held.

Dele came home at a time we all believed was a period of momentous transition. Our assignment at the Times, bluntly enunciated by Tony Momoh, the then editor, was to bend over backwards to encourage the soldiers to depart. We were all concerned that under any imaginable circumstance, a civilian democracy was better even than a benign military dictatorship.

Dele thought we were fools, believing as he did that there was no difference between soldiers and civilians in government. As it turned out, he was right, and we were wrong. Once the civilians came, Dele was quite certain he no longer had any business with the Times, a state-owned organ. He assured us our new rulers were incapable of distinguishing between the interests of the state, and those of a passing government. And again he was right.

When he moved to the Concord group, some of his friends charged him with moral opportunism. But it was an unjust charge. He was already thinking of a magazine of his own, but knew he needed more time to raise the capital for such a project. The only way he could remain permanently with the Concord, or any other media house, was if he could bend it to his peremptory will.

At the Concord, that was an impossible prospect, and his departure from it was inevitable. And then came Newswatch. Newswatch was and is quintessential Giwa. Great historical movements, grand ideologies and profound meditations did not interest him. Human beings, in their solitary deformity and glory, did. What men did, not what they said, was real. What they did in secret was even more real, and it was the duty of the journalist to strive always to close the gap between appearance and reality.

Dele Giwa always uncomfortable with secrets. He did not like them, because they imposed an unfair burden on the journalist. The human condition was for him a public, not a private condition, and the security of the lowly and powerless citizen lay precisely in making all things possible.

I do not wish to be misunderstood. His objection to secrecy did not spring from some arcane political philosophy. It was for him a practical principle of journalism. But in a culture in which the most significant life was lived in secrecy, in which journalism, as Dele knew it, was in fact an aberration, it was inevitable that his motives would frequently be brought to question. But there was no malice in him.

He could do and say outrageous things, but he bore no bitterness for anyone. He did not trust anyone who had power or money, gut he had no qualms dining or drinking with them, provided they did not seek to corrupt his dedication to truth.

Dele loved life. Not the complex, tragic life of the philosopher, but the visceral, dramatic life of the warrior. He called me a corrupted seminarian once, and suggested that I returned to my books, while the arena of public action was left to those who were not afflicted by enervating doubt.

He lived his life, and was absolutely certain what he must do. He lived by his own principles, and he died for them. All of us will die. But precious few of us will, in death, be certain precisely what it is we died for. Dele died well. His life was dramatic, his death even more so. No one can ask for more. So let it be.

– The Guardian, Sunday, October 26, 1986