My Newswatch Years

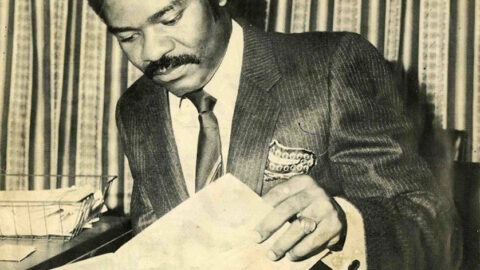

While writing for the Concord newspapers as the London Correspondent, I had the fortune of meeting and starting a memorable relationship with Dele Giwa who, at that time, was the Editor of Sunday Concord. Before I left Nigeria for London in August 1978, I had come across the name Dele Giwa on the pages of Daily Trust of Nigeria. He had been writing and reporting for the Daily Times from New York.

I took notice of him because of his uniquely enchanting style of writing and the general understanding he had on the issues he wrote about. He became a role model for me. I wished to be like him one day, and be a foreign correspondent filing stories to Nigeria from abroad. Therefore, I was delighted when I saw Giwa was one of the journalists of Chief M.K.O. Abiola had recruited to start the Concord group of newspapers and was editor of the Sunday Concord.

As Sunday Concord editor, Dele Giwa somewhat reinvented the art of newspaper production in Nigeria. He introduced the unusual airy and elegant layout and stylish tabloid fonts, which made Sunday Concord different and more appealing to read. The reporting and writing style was also different. Additionally, the magazine section, which he introduced as a pull-out in the middle, made the newspaper more refreshing. It had plenty room for human interest features and news analysis than hard news stories. All combined to make it very entertaining—a family newspaper and a compulsive read every Sunday.

It was not unlikely to find readers across the country holding on to their copy of Sunday Concord, flicking through its pages and waiting the whole week patiently to devour its contents until a new edition came out the following Sunday. Dele Giwa brought the American style of combative and campaigning journalism into the journalism scene in Nigeria. As an editor, he was a breath of fresh air in Nigerian Journalism, which was already renowned for its assertiveness and remarkable courage for speaking truth to power.

This was especially the case when the country was fighting the British colonial masters for independence and when it was under military rule for almost 30 years, with draconian press-gag laws in place. Dele Giwa was himself arrested and sent into jail on several occasions by the military for no other reason than doing his job as a journalist. It was at Concord newspapers that I first met him one on one. He was one of the first Concord editors I introduced myself to and held meetings with when I was appointed as London Correspondent of the newspaper group. When I met him, I noticed he was the opposite of me in character. Unlike me, he was not reserved.

He was more of an outgoing and expressive type of person, which was perhaps a reflection of the environment in which he had trained, the United States of America. This was different from the more conservative British attitude I had imbibed; also, I am a quiet type by nature.

Nonetheless, we gelled and took to each other immediately. Having been trained in the United States, he knew little about the United Kingdom. I even doubt if he had ever been to London when I first met him in 1980. When I invited him to come on a visit, he told me he didn’t like coming to London. I convinced him to come, telling him that I would take him around.

I told him by the time he knew the interesting places, like the shops and other sites of interest, he would fall in love with the city. Then he would at least want to pass through London when going from Nigeria to America to see his family. He had two boys, Dele and Tunde, with his former African-American wife, Anne. He would always go back to New York to visit and spend some time with them. That was how I managed to convince him to come to London, which he did when I assumed office as London Correspondent. In the excitement of his arrival, I parked my smart BMW Three Series car on a restricted double yellow line outside Heathrow Airport.

By the time I came back out with him, we could not find the car! It had been towed away. I felt very embarrassed because I should have known not to park there. “Welcome to London”, I said to him. Dele Giwa waited patiently and kept himself busy reading a book, as I went with one of those famous London black cabs to the nearby car pond where my car had been towed to get it released. I went back to pick him. We drove to my house in northwest London where he stayed with me throughout his visit, before travelling onward to New York to see his family. That was how the personal relationship between us started.

From then on, whenever he was in London, he would stay with me at my house as my personal guest. And whenever I travelled to Nigeria, I started staying with in his house at No. 11 Adolphus Davies Street, behind the Airport Hotel, in Ikeja, Lagos, as well. Dele Giwa was a dandy. I introduced him to exquisite London stores like Selfridges, Harrods, Herbie Frogg, Gerald Austin and so on. He particularly liked Selfridges Stores on Oxford Street where he would pick his Kenyan coffee and some nightgowns. His appetite for the top of the range was insatiable. He always bought his underwear at Marks & Spencer—he liked pure cotton materials.

He fell in love with the shoe shop, Russell and Bromley, where bought mostly his snazzy slippers and shoes. He also patronized the Nigerian Ogunlesi Brothers of the Sofisticat fame when they operated a store and showroom in West London. On the very rare occasion when he decided to stay in a London hotel, he preferred to stay at the Westbury on Conduit Street, Off New Bond Street. Our personal relationship became deeper, and Dele Giwa became a great influence on me.

He particularly impacted my own growth in journalism. When I first joined Concord, I filed stories regularly for the daily National Concord. But I had always liked and kept the Sunday Concord in view with the hope of eventually doing stories for it, too, from London. After spending some time familiarizing myself with the house style of Sunday Concord, I decided to file some feature stories for the newspaper. I sent those directly to the editor Dele Giwa.

His reaction when he received my first stories endeared him to me even more. It was unlike the experiences I had had with other editors I had worked with in Nigerian journalism. I believe this was, again, a reflection of his American training and exposure. Immediately upon receiving my copies, he picked up his telephone to call me in London, all the way from Lagos.

First, he said he was calling to acknowledge receipt of my stories. This is itself was unusual of a Nigerian editor then, from my experience. Secondly, the fact that I accompanied my stories with pictures supplied to us by the Associated Press (AP) in London, showed that I was already well ingrained in the true tradition of British journalism. Thirdly, and most importantly to me, he tole me that he really liked my stories and my style of writing.

However, he said he would want to give me some advice and suggestions on how to improve my style. He went through this with me painstakingly on the phone, and I took notes. It was a long but rewarding telephone conversation. Dele Giwa ended by saying that if I could make the suggested adjustments to my writing style, he would like me to file for him regularly. He said he would give a column to write for the Sunday Concord, which he named himself as London File.

The significance of having a regularly column in a major national newspaper like Sunday Concord was certainly not lost on me. I knew it would give me further exposure and boost my career in Nigeria. It was an attractive incentive, which made it imperative for me to take the editor’s advice even more seriously.

So that was how I started writing my regular London File column for Sunday Concord and did some exclusive investigative stories for the Sunday newspaper Afrom London. In the United Kingdom and the United States, and most likely in other developed countries of the world, there are two important tools one is equipped with on one’s appointment as newspaper reporter — a laptop and a company credit card.

These are considered essential tools for a reporter to make his work easy. One can travel at any time and file stories from any scene of newsworthy incidents. And from wherever one is, one is always in constant touch with his editor, or vice versa; one can give regular updates on progress being made on stories one is working on.

Apart from writing my regular column London File, I did several investigative stories for the Sunday Concord from London, including the 6 March 1983 grossly inflated ballot box contract story under President Shehu Shagari’s administration. And the 27 March 1983 story of Shagari’s armored jeep which he had ordered and was being manufactured specially for him for campaign in the 1983 general election.

Also, I cannot forget the gripping story of the five Olumide girls – aged 2 to 9 — who perished in a ghastly London fire, published in the 19 June 1983 edition of the Sunday Concord, just to mention a few. As a former reporter with the world-famous and prestigious New York Times, himself, Dele Giwa returned back home to the Nigerian journalism scene he had left in the early ‘70’s. Back then, he was a reporter with Radio Nigeria in Ibadan.

As an editor in the true tradition of developed world journalism, he mentored and established a professional relationship with all his reporters and photojournalists. They all loved him too – so much that they would always want to work with and for him. Any time Dele Giwa was in London, I would throw parties for him, and we would also attend parties together. We had plenty of fun together. He liked his cognac and made a ritual of brewing his coffee himself. He was a lover of good music.

He particularly liked Michael Jackson’s songs which he danced to like a kid. He was also a big fan of Paul Simon. He loved dancing to his famous Graceland track, “Diamond on the soles of her shoes.” He loved jazz music, too, especially works of Earl Klugh of which he had a complete set.

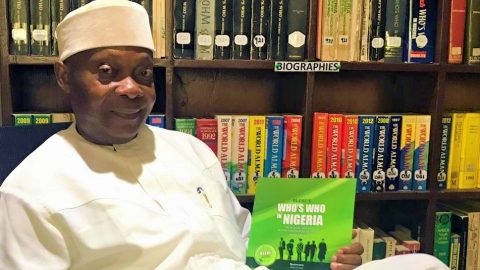

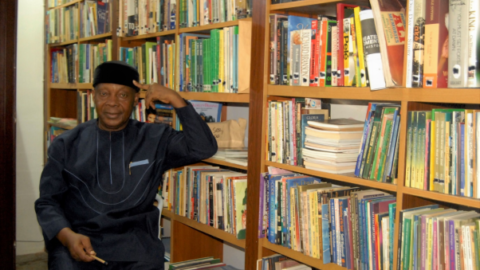

Our relationship had waxed this strong that when Giwa and some of his colleagues and friends, Ray Ekpu, Yakubu Mohammed, and Dan Agbese, established Nigeria’s foremost weekly newsmagazine Newswatch, they appointed me London Bureau Chief. This was while I was still working under the legendary Nigerian editor and publisher Peter Enahoro as General Editor of Africa Now.

My relationship with Dele Giwa, Yakubu Mohammed and Ray Ekpu had been very close since our Concord days. But I only met with Dan Agbese for the first time when he teamed up with Dele, Yakubu and Ray from the New Nigerian newspaper to start Newswatch. Dan was editor of the New Nigerian, which was an influential national newspaper, with a very conservative northern Nigeria bent. If one wanted to know the thinking of the northern Nigeria on any topical issue, one would read the New Nigerian. It was the indisputable and most authoritative voice of the north. Dan is one of Nigeria’s most prolific writers and political and social commentators.

He is a well-experienced and well-respected journalist and editor who is also a complete gentle man. My relationship with the four of them became so strong that we all knew each other’s family very well. For me, it was a relationship of bosses, brothers, families, and friends all rolled into one.

This was the strongest and most enduring association I ever had with people I worked with – including the editor Soji Akinrinade. It is a relationship that I still cherish today. They are thorough professionals, and very deep in their thoughts. Above all, they are honest people with proven integrity. Once they made up their minds that they would be starting Newswastch, I saw an opportunity there to exploit. I made a pitch for helping them their London Bureau.

Dele Giwa and I were regularly discussing the possibility. He had bought the idea and his colleagues, to the best of my knowledge, did not raise any objection. In any case, I had already made myself available to them in London by helping with whatever they needed abroad in their start-up preparation. They held several meetings in London preparatory to the establishment of Newswatch, in which I was always present. This was particularly so in the meetings with a prospective investor who lived not far away from me in northwest London and happened to be close to Mohammed. The negotiations with that potential investor fell through eventually.

When a new set of investors were found, and work started on establishing Newswatch, I introduced to them the companies that I had dealt with when I was at Concord to help out with the procurement of newsprints, equipment, and some other needs. As they were putting all hands-on deck to launch the magazine in Nigeria in February 1985, I was also putting my plans together to help them to establish its London Bureau. I thought it would be a feat if we could launch the magazine in Nigeria and open its London Bureau simultaneously.

In fact, it would not just be a feat, but it would send a strong signal and declaration of intent to the world of the kind of serious journalism to expect from Newswatch. It would give the magazine instant international recognition and clout, making it a truly international magazine that it wanted to be known as.

To put it in proper perspective, what these four great Nigerian journalists were trying to do was unique in the history of the journalism profession and trade in Nigeria. there had been newsmagazine established before, but they were not with the seriousness and regularity of a weekly, similar to the long-established, well regarded and world-renowned American-owned Time magazine, for example.

The similarity in style of reporting, layout and general format between Newswatch, when it was launched and Time was striking. Secondly, it is very rare to find journalists who are good in their trade and at the same time are good business people. Usually, it is either one is a good reporter or a good editor. It is rare to find someone who is good at both and at the same time, is a successful publisher delving into the realms of business. The truth is, most successful journalists are not good businessmen and entrepreneurs. Examples abound of exceptionally good journalists who became publishers but failed after producing their publications just for a short period because they couldn’t sustain them. Dele Giwa, Yakubu Mohammed, Ray Ekpu, and Dan Agbese, had a proven record as excellent journalists and editors. However, could they become good businessmen and publishing entrepreneurs? The jury was out to judge them. To put into perspective what they were trying to achieve in Nigerian journalism at that time, even in global newspaper publishing, it was only in the United Kingdom that three top journalists braved it to come together to challenge the traditional order of things.

They broke the mould of the British newspaper industry by establishing a new independent broadsheet appropriately named, The Independent. Led by Andreas Whittam Smith, Stephen Glover, and Mathew Symonds, who were journalists from the Daily Telegraph, The Independent was launched on 7 October 1986, a year and eight months after the launch of Newswatch by the four Nigerian journalists in Nigeria. and just like Newswatch in Nigeria, The Independent had been established to challenge the monopoly of the Rupert Murdoch and Michael O’Reilly owned broadsheets. It deliberately came to compete in the market with The Times and The Guardian as journals of record. They took advantage of modern technology and embarked on cover price slashing to compete favorably with the long-established broadsheets. The Independent became so successful that by 1989 its circulation had reached 400,000. It had to be sold in 1998 to the Irish newspaper tycoon, Michael O’Reilly, for £30 million. And to mitigate against the drop-in advertising revenue, which most newspapers had started to suffer from, The Independent became a digital newspaper, publishing only online, since 27 March 2016.

So it had been in Nigeria too, when Giwa, Mohammed, Ekpu, and Agbese launched the campaigning weekly Newswatch, in February 1985, to break the mould of newspaper and newsmagazine publishing in the country. Newswatch became an instant hit. It achieved a circulation close to 100,000 copies weekly across Nigeria then. It was so popular that copies vanished from the newsstand as quickly as they got there.

Its success inspired other young independent-minded journalists who were fed up with being used by businessmen-turned-publishers, or politicians-turned-publishers, to start their own newsmagazine business, too. It will not be incorrect to say that Newswatch blazed the trail of weekly newsmagazine publishing in Nigeria. establishing the London Bureau of Newswatch required a lot of money, judging from the level of funding I had at my disposal while setting up the London Branch Office and Bureau of the Concord Press of Nigeria.

Therefore, genuine fears were raised by some external directors about the wisdom of opening a Bureau in London, especially when it may not be adequately funded. The truth is, having a foreign editorial Bureau in an expensive city like London at that time was not a money-making venture; it was more for prestige purposes.

But unknown to them was that I had done my homework. I had come up with a plan on how we could achieve this with a minimal outlay of funds. This was sure to make our competitors wonder how we got the funding and resources to do it. I had learnt from my Concord experience that even where money was not an issue, and a lot had been expended to establish a Bureau in London, in reality, it meant that one was effectively running a business in the city. And if the proprietor of the newspaper or magazine were truly a businessman who worked hard to make his money, he would not just spend his money on maintaining an editorial Bureau and only get prestige from it, but he would also expect financial returns from a huge investment like this one.

I got to that crossroad in my running the Concord London Branch Office when even Chief Abiola, as wealthy as he was, started to look at the books and wondered about the financial sense in keeping such an outlandish editorial outpost in London, even though he liked and was enjoying the prestige it gave him and the newspaper. There came a time when I was put under pressure to make the Bureau self-sustaining for Concord. It was an impossible task, but it made business sense to have such an inspiration.

However, at that time, having a Bureau in London mainly added value to the overall operation of a newspaper group. But we did something to innovative to at least generate some income in London for the Concord Bureau. We started to fly into London everyday copies of the National Concord and Sunday Concord. London, as it happens, is a second home for Nigerians. It has large Nigerian population who have a thirst for news from home. It was not the era of the internet or social media so there was no other means of getting news about home other than reading the newspapers that came directly from home.

Therefore, we created a market for the sale of Concord newspapers in London. Chief Abiola himself put a telephone call through to Nigeria’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom at the time, Alhaji Shehu Awak, with whom he was a member of the ruling political party, the National Party of Nigeria (NPN). He took permission from him for the Concord newspapers to be sold at the High Commission at 9 Northumberland Avenue, the Consulate on Fleet Street, and the welfare section at Inverness Terrace in West London.

We devised a method of clearing the newspapers post-haste when they arrived at Heathrow Airport every morning. And they always went straight to the sales points at the High Commission and other places we had identified around London. We focused especially on areas with a large concentration of Nigerians; these included confectionery stores where Nigerians bought food items regularly. Before long, awareness was created around London, and throughout the UK, that Nigerians could get authentic news from home through the Concord newspapers every day.

We also started a subscription service for the Concord newspapers at the Bureau. Subscribers could either walk in to pick their copies or could receive it by post. The good thing about posting was that we could post copies either on a daily or weekly basis to subscribers wherever they were in the United-kingdom. We also had vendors who would come to the office to collect draws to sell around London. They were mainly Nigerian students who were looking for opportunity for employment to make some money to maintain themselves while studying in the UK.

Before we introduced the sales of Concord newspapers to London’s streets directly, the only place Nigerians in the United Kingdom could go to read newspapers from home was at the London Office of Daily Times of Nigeria on Gray’s Inn Road, which had a proper reading room. It was like a meeting point for some Nigerians to engage in passionate discussions about topical events back home. What we did with Concord by getting Nigerian newspapers to London streets directly is that we established a fairly strong market for sales of all Nigerian newspapers in the UK, most especially in London. Newswatch could take advantage of this fact when it was launched, and its London Bureau was opened. It was on the basis of this experience that I put forward a business plan to Newswatch in Nigeria on how to establish a London Bureau for the newsmagazine. It was not be on the scale of Concord newspapers or the Daily Times. On the contrary, it would be very cost-effective in a way that would cut off the enormous overheads the two big Nigerian newspapers were carrying in London. At the same time, it would give Newswatch a prestigious presence in a key global city and world capital of journalism like London.

The Newswatch editors gave me their full backing and support. With that assurance, I resigned my appointment at Africa Now. I was formally offered the job of London Bureau Chief of Newswatch with a letter of appointment signed by Managing Director, Dan Agbese, dated 14 December 1984. My appointment was with effect from 1 January 1985. It was for three years in the first instance, but renewable. With my appointment confirmed, I immediately got Newswatch an office space within the posh business premises of 50a Pall Mall in southwest London. Anyone who is familiar with London would know the big deal in having a Pall Mall address. The Pall Mall address on the masthead of Newswatch added class and prestige to the new newsmagazine that could not be quantified in terms of Niara and Kobo. Dele Giwa informed me that one external director not only complained but objected to Newswatch having its London Bureau at Pall Mall. I laughed it off for lack of vision and not thinking big. The Newswatch founding editors had convinced me that they had big dreams for the new newsmagazine they had just established. I was in sync with their vision, and I was also thinking big with them for the magazine. They wanted Newswatch to be a truly international and internationally acclaimed newsmagazine and therefore gave it an appropriate sobriquet: “The International Newsmagazine.” I was so delighted that they gave me full support for what I did for them in London.

Our Bureau was next to the prestigious Marlborough House, the home of the Commonwealth Secretariat. And it was just five minutes’ walk to Buckingham Palace! The proximity to Marlborough House made it so easy for me to attend to press conferences there; also, at the shortest notice, to visit the eminent Nigerian diplomat, Chief Emeka Anyaoku, then deputy Secretary-General, and when he became Secretary-General of the Commonwealth. In actual fact, I had worked very closely with him, reporting exclusively for Newswatch on his campaign for the Commonwealth Secretary-General’s post. Once the Bureau was established, I engaged the service of a PR agent, Roger St. Pierre, to introduce Newswatch to Fleet Street. Through Roger St. Pierre, I held meetings with several media page editors on Fleet Street and presented Newswatch to them. Mainstream press like the preeminent journal of record, The Daily Telegraph, lifted quotes from stories and articles in the editions of Newswatch I presented to them. Important people saw this and called me to commend us because it was very rare then to see a positive Nigerian news item in such prestigious British newspaper on an ordinary day.

Mainstream media in London only reported Nigeria whenever there was a coup d’etat or something negative had happened in the country. The Biafra Civil War of 1967 to 1970 which caused the death of between one million to two million people had given Nigeria a terrible image problem among journalists on Fleet Street. The joke among British journalists on Fleet Street at the time, in the 1970s and 1980s, was that it would take a visit to Fleet Street by the Nigerian Head of State or President himself to change the minds of British journalists about Nigeria and appeal to them to start looking at and reporting the country positively; and let bygones be bygones and put the Biafra experience behind them. The Biafra propaganda during the civil war was very effectively globally, and many journalists and newspapers and electronic media around the world were very sympathetic to the Biafra agitation.

Presenting Newswatch to Fleet Street was done as a prelude to the formal launch of the magazine in London. In similar fashion to what I did in 1981 for Concord, Newswatch was launched with fanfare on 5 December 1985, more than six months after it had been already introduced to the newsstands in the sophisticated London market. It was launched before a gathering of top British editors, diplomats, and business people, especially those dealing in Anglo-Nigeria trade.

The Nigerian acting High Commissioner in the UK at the time, Ambassador Ibrahim Karfi, presided over the launching for us. That was how Newswatch started doing business in the United Kingdom. Immediately I settled the magazine’s business down in the UK, I made a move to extend its research to the huge and more lucrative United States of America market. Just like in the UK, there is a huge Nigerian diaspora in the USA. We appointed a key New York distributor to put the magazine on the newsstands in both the US and Canada. In no time, they noticed our presence in London.

Extract from his new book: Born into JOURNALISM