By the time you finish reading this, you may discover the need for a non-negotiable upward review of your respect level for that small clan of egg-heads called professors. You want to know why? Simple!

Becoming a professor does not come cheap—not in Nigeria. In fact, Nigeria is one country—among a few others in the world—that the path to becoming a full professor is so narrow and thorn-filled that many candidates would rather give-up than die in the race. Are you sweating already?

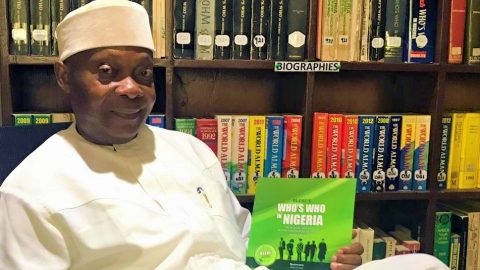

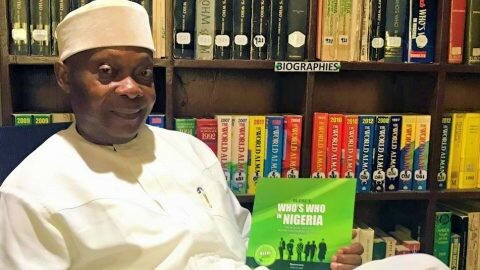

While you think about that, permit me to say that the publication: National Universities Commission Directory of Full Professors in the Nigerian University System 2017 may not be your kind of read—because it is not a book in the conventional sense.

It is a directory—though in a class of its own. First, it is put together by a storehouse of professors. Yes, you heard me well—an assembly of full professors; not mere faculty teachers. Second, it is authoritative—because it is published by the National Universities Commission—and it is the first of its kind in this part of the world.

Although still in its draft form, I perceive that this publication is bound—on completion—to generate as much academic interest as it surely would be controversial.

It would attract intellectual curiosity because it chronicles for quick reference, the bio data of every confirmed professor resident and teaching in any Nigerian university. This will naturally attract attention from students, researchers, teachers, professors, government and the public.

Controversy will however erupt when those who believe they should be mentioned in this all-important publication are not. The Directory—apart from stating the names of full professors—outlines for easy reference, the qualifications, status, areas of specialisation and contacts of these full professors.

Therefore, any person who is not listed in this reference material cannot claim to have reached a full professorial status in the Nigerian university system.

Big names in academic community are involved in the preparation of the directory. Leading the pack is the Executive Secretary of NUC, Professor Abubakar Adamu Rasheed. If you think that is intimidating enough, you should know that he is next in hierarchy to Emeritus Professor Ayo Banjo who serves as Chairman of the Board of NUC.

Professor Peter Okebukola, former NUC Executive Secretary is the lead consultant and chief coordinator of the project. Formatting and editing are co-handled by Dr Remi Biodun Saliu and Dr Joshua Atah.

National Universities Commission Directory of Full Professors in the Nigerian University System 2017 is a-work-in-progress. It is not clear when it would be completed and released officially. However, it is expected that Nigeria’s Vice President, Professor Yemi Osinbajo, SAN, will write the foreword while Education Minister, Mallam Adamu Adamu, will write the preface.

By the way, the foreword of a book is a preamble or introductory statement about the book. It is usually written by someone who may not be directly involved in the project but must be an authority on the specific area of discourse.

A preface has almost the same characteristics as foreword except that it is usually written by the author of the book or someone closely connected to the project.

The Directory—even in its draft form—is already 506 pages long. Faculties and Disciplines already covered include administration, agriculture, arts, basic medical sciences, computing, education, engineering, environmental sciences, law, management sciences, medicine and dentistry, pharmaceutical sciences, sciences, social sciences, veterinary medicine, etc.

While some disciplines and faculties boast of several dozens of professors, computing has just eight. Three of them teach in Babcock University, two others are at the Federal University of Technology, Akure, one teaches in the University of Benin. It is however not mentioned where the other two professors are based.

One aspect of the publication that is quite interesting presents a summary of the history of the Nigerian University System. From this account, the idea of having a university in Nigeria was conceived in 1943 when the famous Elliot Commission was set up by the colonial administration.

Five years later, the University College, Ibadan, an affiliate of the University of London, was established.

A turning point however came in 1959 when the Ashby Commission was set up to study and advise government on higher education needs of the country within the first 20 years of independence.

Before the report could be submitted, the University of Nigeria Nsukka, was born in 1960. But it was the implementation of what came to be called the Ashby Report that resulted in the establishment regional universities—also called first generation universities—in 1962.

They were sited at Ife, Zaria and Lagos. Curiously, the University College, Ibadan was not accorded a full-fledged university status until 1963. The birth of these first generation universities also marked the establishment of the NUC. The package was completed when the then Midwestern Region established the University of Benin in 1970.

Between 1975 and 1980 under the third National Development Plan, the next batch of universities were established in Calabar, Port Harcourt, Sokoto, Ilorin, Jos, Maiduguri and Kano.

These were tagged second generation universities. Between 1980 and 1991, specialised universities were established in Owerri, Yola, Makurdi, Akure, Bauchi and Abeokuta. It was also during this period that state universities were established in Rivers, Anambra, Lagos, Osun, Imo, Cross River and Ondo States.

Some of these universities were later taken over by the Federal Government. We also had the University of Abuja and the University of Agriculture in Umudike. These formed the third generation universities.

Permission for establishment of private universities came in 1983. What followed was a disorderly rush. Government wielded the big stick and all the 31 private universities were shut down. Ten years later, the military regime issued Decree 9 of 1993 which lifted the ban. It came with strict control. In 1999, the first three private universities were licensed.

The Directory outlines the aims and objectives of higher education in Nigeria based on the National Policy on Education (2014).

It is a sad admission by this body of academics that despite the laudable goals of higher education in Nigeria, this sub-sector has suffered from certain challenges that have undermined its quality.

They include paucity of academic staff and insufficient and degenerating infrastructural and instructional facilities. The publication blames inadequate admission slot in universities on low patronage of polytechnics and colleges of education.

There are eye-popping statistics that should give our policy makers in the education sector something to think about. For instance, in 2017, Nigerian universities had over 2300 programmes with academic staff strength of only 51, 000.

In 1962, we had a little over 2000 students in all Nigerian universities. In 2017, we had over 1.9 million students. In 2018, we had far above two million students; with no significant improvement in infrastructural facilities.

Before I forget, if you are dreaming of becoming a professor in a Nigerian university, then you have to first try to push your head through the buttonhole of your shirt. No, I’m not being over metaphorical.

The process is one of the most stringent in Africa. At the global level, it is only compared with what is obtained in a few universities in Europe and North America. No one has explained why the procedure has to be so suffocating.

Here is the summary. First, you must have a doctorate degree in your area of specialisation. If you studied medical sciences, a recognised Fellowship is grudgingly acceptable although there are indications that rules are changing in favour of a doctorate as the acceptable minimum qualification.

In every discipline, after your doctorate, you are required to spend at least three years of teaching, research or community service at each level of lectureship; and there are four such levels. Please add up! Of course, it is not automatic that after 12 years of teaching and researching, you must be confirmed a professor. That is just the second step. The road to the top is narrow and rough.

The third and most demanding step is the assessment of your scholarship. Your published works must be assessed by a senior professor in your area of specialisation.

You must have a minimum of 60 internationally-published works; and 80% of these must appear in what is called “high-impact international journals.”

One of your assessors must come from “a well-ranked university” outside Nigeria preferably in Europe or North America. Only a minimum of two positive assessments from two assessors qualifies the candidate for the next stage of a full professorial possibility.

Scared? Wait a minute! Here is the first leg of the final stage. It comprises rigorous screening of the candidate through oral interview on specified issues such as assessment of the applicant on length and quality of teaching; scores returned by external assessors on the candidate’s research work; internal and external assessment of community service; among others.

The second leg of the final stage is when your final score is sent to the university where you are expected to be crowned a full professor. Each university has its benchmark.

That you score the required marks does not guarantee immediate confirmation and appointment by the University Council as a full professor—especially in the first and second generation universities. So, you want to become a full professor in Nigeria? Do yourself a favour: pray for long life.

The hard copy of this Directory is yet to be published. Even the soft copy is not in circulation. This review is based on a privileged access to the draft. There is no doubt that on completion, it is going to be a collector’s item.

Review by SAM AKPE