By Sam Akpe

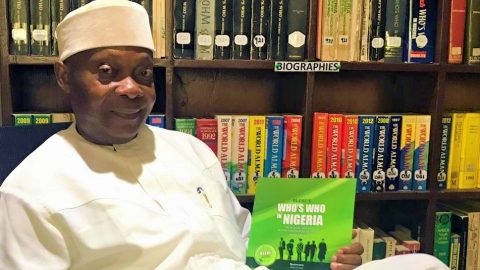

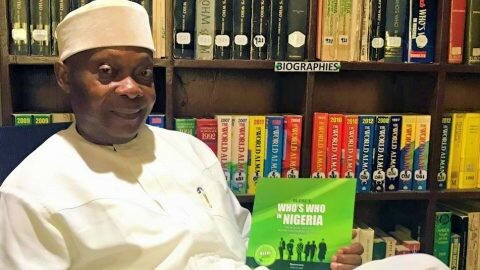

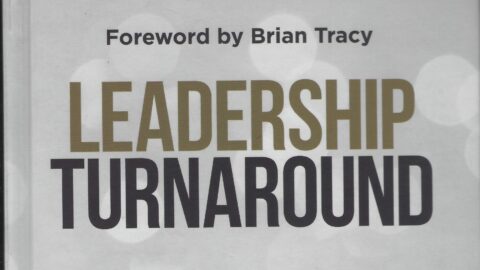

This book has not yet been officially published. When it is, it would surely receive a few knocks and some unembellished praises. Knocks, because of its audacious contents, and applauses, because of its specialised significance and timeliness. The author, Dr George Udoh, teaches communication studies at Ritman University.

Parliamentary reporting is often viewed as the highest level of political journalism—and the most complex, too! This is because the legislature is the most open political arena in any democracy. Its affairs are conducted in the open except when it concerns national security and other issues of like nature.

Another beauty of the legislature is that every lawmaker is sovereign. He owes almost no obligations to institutional hierarchies, except on matters involving Standing Rules and legalities. Unlike what happens in the executive branch where those called to serve do so in subordinating positions, the legislature is a house of equals. Rules are made for everyone and everybody has equal voting rights.

In the legislature, the presiding officer is more afraid of the floor members than the other way around. He is often scared of being ganged-up against. So, more often, he is perceived as a servant, not the boss. Unlike what happens in the executive and the judiciary, the power to sack or suspend a lawmaker is collective and must be constitutional.

Therefore, for any serious-minded political journalist, the legislature is the place to be. Reason: every member is an acknowledged newsmaker—and trouble maker, too. The presiding officer may not speak. The Senate or the House may not be in session. Still, events unfold! Information flows! News is made as members disagree to agree. Mutinies are planned and executed at will. Decisions taken in secrets are leaked without trace.

As unobtrusively observed in this book, most times, legislative reporters cause more trouble with their reports than the lawmakers intended, depending on the media organisation they represent and the interest they seek to protect. Interpretation of events and the general handling of news by the mass media are sometimes based on certain interests not intended by the news source.

This, in a way, is the focus of Parliamentary Conflict Reporting in Nigeria. It is mainly about how media reportage can either create, aggravate or reduce legislative crisis, and what political variables help in making this possible. It is a case study of some incidents that occurred in the House of Representatives several years back with a focus on two former Speakers—Patricia Ette and Dimeji Bankole.

This book is a product of a PhD thesis. Its analysis and conclusions are based on empirical data assembled through research. However, the content has been deliberately expanded to accommodate certain newsroom or journalistic realities—a metamorphosis that has not deprived the book of the natural academic jargons and inferences.

Discourse in the book starts from the military era and fast-forward to mid-1999 when democracy was reinvented in Nigeria’s political space. The author then traces the history of parliamentary conflict in the new dispensation to the sack of both the new Senate President and the Speaker of the House a few months after assumption of office.

The then Senate President, Evans Enwerem, and House Speaker, Salisu Buhari, were reportedly removed on grounds of falsified age and unverified academic qualifications, among other unsubstantiated allegations.

After a thorough analysis of subsequent scandals that have defamed the integrity of the legislature, the author concludes that legislative conflict has imposed a cancerous presence on the law-making chambers, especially, in the House of Representatives.

Dr Udoh mentions and explores certain social ills and administrative defects such as corruption, poor or lack of credible communication strategies, as well as administrative flaws as constituting constant instigators of conflict in Nigeria’s Senate and House of Representatives.

With eight specific research objectives, the book seeks to address the issue of mass media reportage of parliamentary conflicts with focus on how the different cases involving two former Speakers of the House of Representatives were portrayed in the media and how such portrayals heightened or influenced the outcome of the crises.

Although the book passes no judgment of guilt or innocence on anyone, it recalls that Speaker Patricia Ette was accused of involvement in a N628 million contract scam in 2007, while Dimeji Bankole was in 2008 demanded to explain how N2.3 billion was spent in a car acquisition deal for House members.

The question the author set out to answer through analysis of empirical data is principally how the mass media reported both cases and how such reports persuaded the National Assembly in the management of the issues.

The narrative is captured in 21 chapters while the data collected through quantitative research and content analysis methodologies are presented in 36 tables. Sixteen reproduced versions of past newspapers highlighting issues discussed in the book are also published.

The author made allusions to corruption of elected officials, undue executive interference in legislative leadership, political repressions by those who control the machineries of government, and wait for this: political reporting, as key factors responsible for legislative conflicts in Nigeria.

Communication—the oldest and most pervasive of all human activity—is treated in the book with both hypothetical and practical depth, as a factor in conflict creation, conflict management, and conflict resolution—whether in the legislature or elsewhere.

While concluding that communication and conflicts are interwoven, the author’s scholarly but suppositious perception, is that conflicts usually arise from defective communication behaviours and that their intensity can also be minimised through the same channel—application of functional communication approach.

The literary beauty associated with this book lies in the interconnectivity of issues—from communication to leadership in the House of Representatives, to political conflict, and the roles of the mass media.

Dr Udoh believes that Nigeria’s political conflict, even in parliament, stems from the multi-lingual, multi-cultural, and multi-religious construct of Nigeria. Even if this was conjectural, he certainly has a point. His analysis of the variables is deep and persuasive.

The author’s seemingly authoritative deduction, based on findings, is that most of the mass media reports of such conflicts in terms of editorial slants and depth of analysis are based existing tribal loyalty, religious leanings, political interest, and certain social groupings that make up Nigeria.

He comes down heavily on parliamentary political leaders, whose conducts he describes as habitually immature, immoderate, mostly irresponsible, and capable of igniting conflicts where there is none. His conclusions are however not based on any reliable experiential evidence.

Generally, certain claims made in the book, though seemingly or street-wise factual, lack verified backgrounds. However, the book speaks volumes when viewed against its discourse on instances of major conflicts in the House of Representatives from 1999, the role of the media, causes, and their disparaging impacts on the institution.

From a journalistic perspective, the author tried to draw a line between news coverage and news reporting before delving into a discourse on factors that can influence a reporter and his coverage of the legislatures. These journalistic jargons and semantics are likely to trigger deeper discussions when the book goes public.

Of particular interest is the author’s focus on conflict reporting, its social responsibility implications in a developing democratic society such as Nigeria, the journalistic tools required in legislative reporting, and the attitude expected of a legislative reporter. This is an area that should attract further exclusive studies by academics.

It is not clear whether Dr Udoh has ever covered the legislature as a reporter. I do not think he has. However, being an academic gives him the advantage of observing, studying and understanding, at least theoretically, the requirements and importance of the beat. The book views legislative reporting as a serious aspect of not only political journalism, but news gathering and analysis generally.

The meat of the book, which is the methodology adopted by the media in their reportage of the Etteh and Bankole scandals, is discussed using a combination of variables that define both the practical and the theoretical aspects of journalism. Here, tables indicating research data and versions of published stories on the conflicts are analysed.

After dissecting the roles of the media in conflict reporting, the focus shifts to the newspapers and their role in the reportage of the specific scandals, which almost permanently rubbished the integrity of the House. Using the data collection results, he reviews, not just the role of newspapers, but also their intent, formats, contents, among others.

Anchoring the narrative on perception, he deliberates on media credibility, fairness, threat to democracy, imagery, prominence, conflict management, inevitability of conflicts, and independent opinion of journalists.

The book establishes a supposed connection between the Etteh and Bankole conflicts to institutional corruption, political power, poor communication strategies, administrative flaws, leadership insensitivity, public affairs reporting by journalists, and the collapse of party supremacy.

These issues are handled with almost impeccable academic, historical, and literary excellence. They are presented as key factors that directly contributed to the deadly struggles in the House of Representative at the time under discourse, and beyond.

The book equally observes that the massive reportage of the conflicts by newspapers was aimed majorly at bringing to the attention of legislators and Nigerians the need to curb corruption and dangerous power-play in the legislature. He describes media reportage of the events as credible and fair.

Despite certain research and technical drawbacks, the uniqueness of this book is in its combination of academic with applied findings in the discourse of conflicts reporting in the legislature. It does not only read like a fact-based journalism text, but more like a reportorial or newsroom manual—a hands-on reminder of what political journalism was meant to be—and could still be!

Truly, I have enjoyed the draft of Parliamentary Conflict Reporting in Nigeria. It is my expectation that when the final edited copy is published, it would correct certain observed flaws like unverified claims, and non-tested assumptions cited as conventions, and that the different sections and chapters would be made to flow logically.