To live in Nigeria I hear is hard … But as a young Nigerian ….

I hear a ringing call to come home, a call to give the best of me

To my profession and my people. So home I am coming.

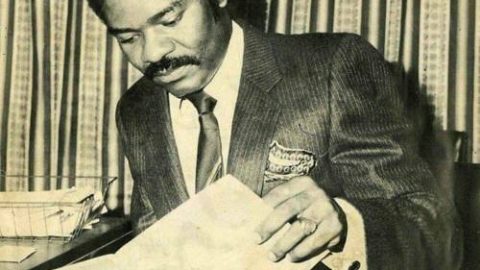

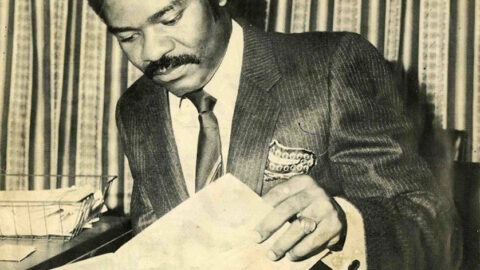

Clearing Kennedy Airport was easy. The stern immigration officer asked the usual routine questions: “Are you a communist or have you ever belonged to any communist organization? Who would pay your school fees?” To these questions I gave the expected stock answers. The customs officer went through my lone box, found it nearly empty and waved me through. Getting to 8 South Oxford Street, in Brooklyn, from the airport wasn’t anywhere as easy though.

The day was in late November of 1971, a time of the year when the arctic cold air begins to blow southwards. It was beginning to get cold in New York. And I had no overcoat. I stepped outside into the chilly afternoon weather in my light, grey polyester suit and felt the cold wind bite my face. Of the 75 dollars I brought with me from Nigeria, I was determined not to spend a penny for a taxi fare.

My hosts were not at the airport to receive me. They didn’t get my cable, which from Nigeria in those days always took longer than a letter to travel. I didn’t have the telephone number of my hosts, so I decided to get to the address on the back of the envelope I was clutching.

The more difficult, I rationalized, the better, for the writer in me wanted an eventful beginning. After four hours underground in the train and underground in the bus and after minutes of reluctant taxi ride, I arrived at South Oxford with my fingertips frost-bitten. I almost succeeded in my dogged refusal to take a taxi and taking one was my first brush with an American con artist.

The train had taken me to Kalb Avenue which is about two and a half blocks to the address at South Oxford distance to travel. Instead of telling me that I was within sight of my destination, the driver took me away from the area, drove me round for about 15 minutes, brought me back and collected four dollars from me. Everything I saw that afternoon destroyed the little script I wrote on my mind: that I would hug the first Nigerian I see.

The first one I saw at airport awaiting someone’s arrival didn’t even acknowledge me. How, I asked myself, would someone see a fellow countryman thousands of miles from home and not offer a hand? The first Black American I met. I wrote in the script, I would embrace.

When I saw one on the bus he didn’t even answer my queries about how to get to Brooklyn from the airport. It took me almost a year to understand the Black American a little; that with his problems – poverty, racism and lack of identity – he couldn’t readily afford the affection for the stranger from “home”.

Black Americans are actually sweet fellows. We owe them much more than we know. Even more than three hundred years after selling them out as slaves they still try to understand us. Some of them will go as far as to ask why did our common ancestors choose to sell them to white people.

While they try to understand us and connect the missing links in our culture, we treat them with brutal impatience, lie to them and give them ugly names. Point to a Black American and a Nigerian would say akata. For many years Nigerians who came to the United States, in answer to questions from their diaspora brothers and sisters, lied that they were chiefs and princes. Yet we go nowhere else on arrival here. To the ghetto we head, hiding in the sea of blackness and the stench of poverty. Instinctively, we gravitate towards the black for they are of us.

You can’t understand the Black American without knowing his history, and you can’t know America without living there and opening your eyes round the clock everyday. After greeting my hosts and friends on arrival in New York and sitting down to a dinner of chicken and eba made from flour and potato powder, I knew the going would be tough before it got better.

The rosy pictures painted by those colourful and glossy brochures in the American libraries in Nigeria failed woefully to deliver the heaven on earth they promised. America is not, and for that matter, no other country on earth is God’s own. As a Black American saying goes, we are all God’s chillum.

To live well in America, you must work hard. And hard I worked. My first job in a plastic factory brought tears to my eyes. For less than 80 dollars a week and working with a bunch of illiterates, I regretted leaving my reporter’s job at the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation (NBC) in Ibadan.

By the time I was fired from the job two weeks later molten plastic had removed the skin from my two palms and the heat from the plastic moulding machines had killed the glow in my skin. My next job which I paid 125 dollars to get, lasted only three weeks when my Indian supervisor got me fired because of what he called: my arrogance. That was the time I declared in solemn soliloquy that I would never be a factory hand again and would never again be an Indian subordinate envelope pasting sweat shop.

For six months after that, I drove a taxi, first hiring a car and then buying a beaten six-year-old black Chevrolet from a fellow Nigerian. At that time in 1972, driving a taxi was the vogue among thousands of Nigerians in New York, Washington, D.C. and Chicago. It was paying, but denied you time to have fun. Weekends were the best for making the most money, but they were also the times that Nigerians gave their lavish parties which has since tailed off in the last couple of years.

Taxi driving is also no longer the vogue for most Nigerians who have since found better things to do. Police harassment and mugging and stiff competition from Haitian immigrants discouraged many Nigerians in the taxi business. In that period Nigerians constituted a shaming mentally. Some formed social clubs, fought at parties, seduced each other’s wives, distributed narcotics, got thrown out by the immigration and generally made fools of themselves mostly.

Many Nigerian did enough awful things to get many schools and even the immigration department to have special rules for dealing with us. I left taxi driving after I had a near-fatal accident in which my passengers were hospitalized. Then I entered Brooklyn College of the City University of New York where I enrolled for a degree in English – I got a job in a bank, got married, had a son, left the bank and joined the New York Times.

Easily I could have called joining the Times the turning point of my life. For the paper has given me the professional mooring in life. In four and a half years on the paper, I worked on the national, the metropolitan and the foreign desks where I assisted the battery of editors in running the desks. I wrote stories and mastered the bolts and nuts of running a newspaper.

The career at the Times as it were, was capped by a six-month stint at its United Nations Bureau in which I assisted the Bureau in covering the world organization. But the turning point in life came with my father’s death in May 1976. Death, no matter what John Donne, the English 17th century poet said of it, has a presence larger than life. As the most paradoxical element in affairs of man, death, by taking my father away my father, brought me closer to him.

Leaving home in 1971, I promised my father that I would definitely come back to see him. It was a promised solemnly made and we both meant to keep it. Then the news came in a letter in 1976 that my father died suddenly after taking ill on his farm.

That letter, so descriptive of the last moment, spoke of how he held back death and when no more he could fight, he was reported to have told one of my sisters present at his bedside that life and God had been kind to him. The only thing he missed, the letter reported, was seeing Dele again. Since his death, my father directed the waves of affairs and they became kind to me.

The current refused to run counter to my interests. In the United States, where nothing was ever easy for me, they assumed good order. I sailed through graduate school with little ado. I turned towards home and developed a strong positive interest in my country.

Life is often perilous in the United States. Fire, gale and snow kill people as much as stray bullets and the muggers’ knives and chain. This is not to say that America is all brutal death. One would be ungrateful if he wouldn’t say the other truth about America. Very complex and very rich and very poor, America is the truest land of opportunities.

To me, this country has been kind. It has given me guile and knowledge and certain polish just as it has given thousands of other Nigerians who, like me, come here yearly with high school education, a few dollars and a few shirts, but leaves as fully developed men with better grasp on their live.

My story is actually the story of many a Nigerian who came to the United States looking for the golden fleece and who returned with something that looks like it.

An American Experience

To leave the United States or live in the United States. That’s the question. To live in Nigeria I hear is hard. Robbers send you letters. The water doesn’t run. Electricity flickers. Travelling the roads is much like heading for hell. It is tough self-query that presents two false choices: to leave America is hard. If nothing else, it means leaving behind my two sons.

Something else, here I have lived for some 90 months. Months of learning and of growing and breeding, the most active seven years of my life. But as a young man and as a young Nigerian, I feel a strong pull by my country, I hear a call to patriotism and a call to duty. I hear a ringing call to come home, a call to give the best of me to my profession and my people. So home I am coming.

My life in America: no one single event qualifies as the most important. Everything is somehow connected. Leaving Ibadan, where I was a reporter, for the United States, I knew that in the other worlds I must learn to be a good journalist and, of course, must have good education. Thank God, all that I did. B.A. in English, M.A. in Public Communications. Four and a half years with the New York Times. And now home I am coming to the Daily Times.

–Sunday Times, April 8, 1979