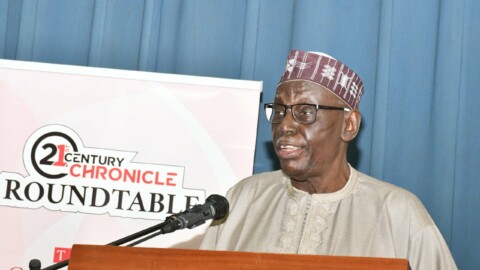

BOOK REVIEW BY SAM AKPE

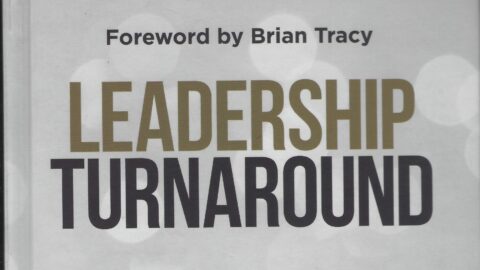

Have you seen the book? It is entitled Age of Videots. The first question that comes to mind is: what is a videot or who is a videot? So, you are reaching out for the dictionary already? I did exactly that. But I am convinced that the word is a coinage or rather a creation of the fertile imagination of the author. It describes someone whose consistent, unapologetic exposure to western cultures and values through movies, the television or any such media has obliterated his traditional values; turning him into someone of low intellectual rating on issues of cultural inheritance. Gbam!

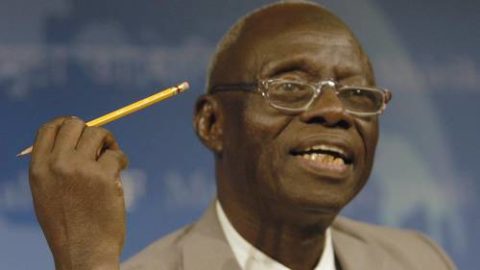

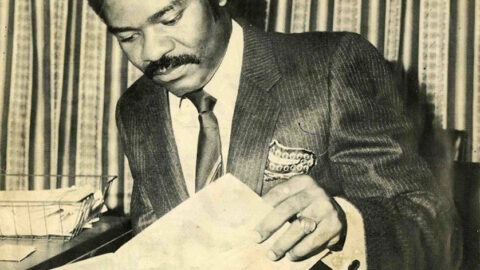

If you ignore the unusual title and turn the pages—which are a little over 150—you are likely to have some intellectual fun. The book is a compilation of newspaper articles written by Dr Udeme Nana on several issues between 1983 and 1997. Beginning from 1983 when he left secondary school and started stringing for the Nigerian Chronicle in Calabar, there has been no stopping him. When you compare the quality of stories he wrote at that time—in terms research and depth of analysis—with what university graduates offer the reading public these days, you are likely to raise more questions than answers.

Someone has defined journalism as history chronicled in a hurry. Quite apt! Does that therefore mean that every journalist is a historian? Maybe accidental historian! Think about it. Reading through this little book may not provide an absolute answer to that; but it could serve as a lead towards a possible conclusion.

The book opens with analysis of the 1983 Presidential Election. Even at that early stage of his introduction to journalism (armed with only his WAEC certificate), Udeme’s full grasp of political events and his almost-accurate prediction of the outcome of the election based partially on the non-preparedness of the Federal Electoral Commission (FEDECO) cannot be ignored. This chapter unveils slowly what the future holds for the young, ambitious political reporter as displayed in his impressive understanding of the political terrain.

The author takes a swipe at FEDECO and its grope-in-the-dark approach to the serious national assignment of conducting a presidential election. Though young and inexperienced in the art as he was at that time, he noted that even the media—especially government-owned—had compromised their sacred, traditional roles with repeated display of partisanship in political campaigns as shown in news reportage and analysis. He was also not lenient with the party in power at the time—the National Party of Nigeria.

Reflecting on the poor state of the economy, he states that this was one reason NPN was not able to impress Nigerians in its campaign for second term. His punchy conclusion that “since independence, Nigerians have never had it so bad,” is followed by a prediction of a possible failure of NPN at the polls. In the same article, he takes a few uncertain steps forward in his political calculation by sweepingly predicting that “1983 might yet be (Chief Obafemi) Awolowo’s finest” political hour because according to him, “Awolowo would emerge victorious.” It was a mere wish that remained a mere wish.

Next, Udeme examines the trials and tribulations of Nigerian politics of 1993. That was the year M. K. O. Abiola won a presidential election that was annulled by the military government. That election was significant in many ways. It was the first time Nigerians were blind and deaf to religious sentiments because both Abiola and his running mate, Babagana Kingibe, were Muslims. It was also an election adjudged as the fairest, freest and most credible in Nigeria.

It was either Nigeria was tired of the military regime and wanted it out or a new era of national integration devoid of religious and ethnic dichotomy was born. But along the line, two dangerous judicial decisions—one stopping the election from holding and the other stopping vote-count and release of results—were pronounced. The National Electoral Commission (NEC) disobeyed the former and obeyed the latter.

When the annulment was eventually announced, there was “thunder in the land.” Violent reactions pushed Nigeria too close to the edge of another civil war. The military leader, Ibrahim Babangida was forced to resign. He set up the Interim National Government which was later declared by a court as illegal and unconstitutional political. More uncertainty! More chaos! Then came Sani Abacha who simply pushed aside the ING, dismantled all democratic institutions and rolled out the full tanks of the military for further enslavement of the Nigerian people. It was Nigeria’s dark days. The next chapter is a profile on the assassination of Muftau Babatunde Elegbede, a three-star navy general, in Lagos.

In a chapter headlined: Age of Videots, Udeme tells the story of man’s negative transformation from the moonlight story telling age to computer age where life has lost its naturalness. He recalls an era when parents used to thrill their children with traditional tales that strengthened morals in them as against today’s undue or unguarded exposure to movies that have weakened such morals because they “do not refine the sensibilities of youths.”

Udeme has a way of constructing introductions in each of his articles. He makes the reader wonder what is likely to follow. He comes across as an excellent opinion writer because of his extraordinary literary and research abilities. This is demonstrated in his success at seeking and infusing fresh facts, analytical depth and unquestionable details in stories you thought you already knew. Opinion writing is not about forcing your personal views on the reader but seeking new facts and convincingly presenting them to sway the reader in the direction of your thoughts.

In Age of Videots, the author applies metaphors and similes with deft ease and clarity. In chapter five, he describes the dethroned military regime of Muhammadu Buhari as “one long night complete with heavy rain which kept people indoors.” Referring to the regime’s deadly interference in freedom of expression, he writes that “man’s freedom was curtailed and mouths were bandaged by the hard cotton of draconian decrees.”

Udeme masterly paints pictures with words to refresh our memories of what Nigerians were subjected to by operators of the regime until August 27, 1985 when, in his words, “Nigerians leapt for joy; people smiled—the rain had stopped, the night had receded; the sun (was shining) again. Then emerged the Prince of August—Ibrahim Badamosi Babangida….” This chapter is more of a picturesque review of the IBB regime four years after he seized power in a military coup; and what happened shortly after.

Concerns about societal discipline are laid out in chapter six. Here, the author picks issues one by one, sector by sector and narrated with authority how the War Against Indiscipline and Corruption should be tackled. From traffic check-point officials who demand bribes to drivers who offer such bribes, he spares nobody as he narrates the depth of corruption in big government corporations.

Arrangement of articles in the book is not chronological. Chapter seven is entitled: Babangida’s Apotheosis. This is a critic of Abacha’s more vicious regime, which he stated made Babangida’s era more of a more benevolent dictatorship. It also explains that IBB was born in August, took power as military president in August and equally relinquished power in August.

This chapter reviews Nigeria under Buhari in harsh words and goes ahead to analyse IBB’s high and low points as military president—something that would be useful to students of political history. The author states that in a breathless deceit for return to democratic government, IBB set up the Political Bureau to collate and crystallise the views of Nigerians about a political arrangement that would strengthen the country’s political system and provide a time sequence for handing over power to democratically elected Nigerians.

The breathless but hopeful manoeuvring resulted in the establishment of the Constitution Review Committee and later, the Constituent Assembly to authenticate the provisions of the new constitution. From creation of more states and local government areas to forcing on Nigerians an economic blueprint called Structural Adjustment Programme, which promoted deregulation of the economy, IBB dribbled Nigeria and Nigerians into a future called mirage. Though “tough, bold and courageous,” he was full of deliberate deceit while all his over-orchestrated economic and political programmes ended in illusion. After stating a few positive facts about Babangida—for example, the introduction of two-party and open ballot systems, which made Nigerians ignore the negative lyrics of tribe and tongue in voting—Udeme concludes that at his exit, IBB left Nigeria more battered, bruised and broken.

In chapter eight, he tells the story of Akwa Ibom State at one year, having been created in 1987. He goes ahead in the next chapter to examine an academic creation called the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, where he got admission to study mass communication in 1986 and graduated in 1990 with a BA and later in 2002 with an MBA. In 2013, Udeme bagged MA in mass communication from the University of Uyo and capped it with PhD in 2017. With a chain of other academic qualifications, the author is currently a chief lecturer at Akwa Ibom State Polytechnic where he had previously served as Head of Department of Mass Communication.

The headline in chapter ten and the lead paragraph will make you ask “so what” But wait until you read the second, third and other succeeding paragraphs. The story is entitled: Life at Nsidung Beach. It is a human interest feature story that explores a typical business day at the beach, which begins at 5.30 in the morning. This is one of the stories Udeme wrote for the Nigerian Chronicle in those days as a school certificate holder while waiting for admission to the university.

If the test of a resourceful reporter is to squeeze news out of an everyday event and make a juicy read of it, Udeme has proven that in many ways in the book by employing simple descriptive prose to tell normal stories in different ways. Chapter 11 is about sports—and Udeme does not seem to be a fantastic sportsman. But every Nigerian seems to be a football lover. Here, he examines Nigeria’s boycott of the World Youth Soccer Championship in Qatar because it was denied the hosting right. He observes that Nigeria lost out on two vital ends—non-participation in the fiesta and unsuccessful attempt at convincing other African countries to stay away.

From sports to politics, Udeme—at the time he wrote these articles—was neither tired nor afraid of taking on the military administration. In chapter 12, he offers a critical analysis of Babangida’s economic and political programmes that Nigerians invested so much hope only for such expectations to be annulled. The author describes the administration as a regime which Nigerians sacrificed so much for but enjoyed no benefits. He states that Babangida annulled “and de-annulled the aspirations of politicians at will and (also) annulled their attempt to organise independent political parties.”

In the next chapter, the author—who at that time was a bubbling youth—bluntly argues that the elders and not the youth are to be blamed for the failure of the society. The succeeding chapter examines in detail the intrigues that usually follow appointment to political offices. Indeed, most times corrupt practices by public office holders are products of desperate attempts by such public officers to redeem promises they made to their godfathers, who sponsored their appointments. When people or communities place too much demands on public office holders in terms of patronage and social elevation, corrupt practices become inevitable.

Chapter 15 of this little but loaded book examines Akwa Ibom State as it clocked six years old. The author quickly headlined the next chapter Nigeria Calls Obey—the second line of the first stanza of the national anthem. In this beautiful prose spiced with historical facts beyond the shores of Nigeria, Udeme is categorical that a time comes in the life of a people when the call to obey must be aligned with the citizens’ cry for justice.

The book, Age of Videots, features articles on various subjects with political issues taking the centre-stage. Writing about science and technology, Udeme states that Nigeria’s backwardness in innovative scientific development is not for lack of manpower and initiatives but a result of obvious discouraging environment. He cries over situations where innovations by indigenous Nigerian scholars are hijacked by foreigners, repackaged and sold back to Nigerians. The next chapter is headlined: The Rot in Education.

Again, Udeme returns to politics as he takes on the military and other uniformed personnel on the issue of civility and courtesies in their dealings with the public. From politics to culture, the author displays his literary versatility in a discourse on the values of traditional festivals to the society. Here, he focuses on the New Yam Festival, which is a traditional ceremony that celebrates the harvest of fresh yams in certain parts of Nigeria.

Mission to Bakassi—a short human interest feature will leave any reader asking for more. Twice or thrice, I was in that former territory of Nigeria called Bakassi when the controversy between Nigeria and Cameroun over ownership was in the air. So when I read this story, I could relate with it easily. Udeme employs his descriptive prowess and a knack for detail in telling the story of his trip to Bakassi—when that island was still part of Nigeria. He went in search of news—that “priceless commodity” lying on slippery and dangerous paths. On arrival, he was arrested and locked up. However, he lived to tell the tale with the nicety and flow of great a novelist.

As if missing his regular beat, the author quickly returns to politics in the next chapter with a focus on the Nigerian politician. With historical facts and figures, he describes the Nigerian politician in the damning words of the great Jonathan Swift, “the most pernicious race of odious vermin that nature ever suffered to crawl upon the surface of the earth.” Hard stuff!

Still on politics, the author approaches the next article in manner that could stretch the curiosity of the reader. It is headlined: Riding the Tiger. The discussion exposes how politicians ride on the back of their constituents to get to power with the seeming forgetfulness that real power belongs to the people. He uses the satirical narrative to describe the fall of both the IBB administration and the Interim National Government headed by Chief Ernest Shonekan. Racing through chapter 25 is allowed. But you need to slowdown as you flip to the next chapter entitled: Who Owns Bakassi? Quoting documents from 1885 to 1913 and beyond, Udeme tells the story of the peninsula in a language and style that are both revealing and captivating.

Conmen have basins filled with tricks, states the author in the next chapter of the book. This is another human interest story with the headline: Antics of Conmen. Without mentioning names, the he tells the story of people and groups involved in the irresponsible act. The story flows into the next chapter which focuses on ghost workers. It begins with the unbelievable narrative about an accountant in one of the ministries who died; and while the children were trying to raise funds for his burial, colleagues within the ministry were still collecting and sharing the deceased’s monthly salary and allowances. This story is a mockery of a system whose record-keeping is not only pathetic but non-existent—an atmosphere that has given birth to a cartel of economic vampires raised and nurtured to feed on the resources of the state.

The story: Thoughts on Rotationalism is the author’s contribution to the growing debate for rotational occupation of elected public offices in Nigeria. Relying on historical facts and contemporary analysis, Udeme concludes that the clamour for rotational election to public offices has the capacity “to throw up third rate, politically weightless candidates.” Above all, it will promote ethnicity and sectionalism at a level that could affect the oneness of Nigeria.

The last chapter of the book: The Flight to Egypt, is another human interest story—perhaps the best in the compilation. Udeme went to Egypt to attend the African Council on Communication Education Conference but ended up digging into the historical significance of whatever his watchful eyes saw in that ancient geographical entity. His description of nature, from “the foamy clouds that rose like mountain peaks in the horizon” to “Cairo’s skyline well-lit by electric bulbs and the soft caressing hues of the moon,” only help wet the intellectual appetite of the reader as he digs deep into the literary expedition.

This chapter is a mixture of history, ancient science, architecture, astrology, magic, and medicine all captured in the sphinxes and the legendary pyramids, which according to the author, constitute another wonder of the world. This is a beautiful read. Udeme captures the story of Cairo in a captivating picturesque manner. In this chapter, he does not write, he paints pictures with words. Egypt naturally is a land of antiquities where the royals among dead are mummified and placed on public display in a museum whose story is as historic as the mind can conceive. These mummies are encased in transparent glass caskets. The stone-dead corpses are so cared for that they look as though they died just some months ago. Of course, they passed on thousands of years earlier. Tourists are not permitted to be noisy while walking past them.

Udeme’s narrative on the ancient country called Egypt and the city of Cairo takes every attention away from the communication conference he went to attend. There is so much to be reminded of and of course, so much to learn as one reads through this chapter. Even if you never believed in Egypt as the cradle of civilization or as Africa’s tourism headquarters, this chapter will likely persuade you in the opposite direction.

An enthusiastic reader and relentless writer, Udeme only took to journalism as a passion. He is a teacher by calling. With four degrees from Nsukka and Uyo, his sojourn or impact in the newsroom was brief and unforgettable. While his eyes were set on rising to the top and becoming a reference point, the pull towards his natural calling was irresistible.

Newsroom, to Udeme, was a mere digression—an opportunity to express himself or fulfil a desire—while raising the next generation of critically-minded reporters and media experts through the classroom remains a mission that must be accomplished. Most of the articles in this publication were written during his internship while studying in Nsukka and when he served as features writer in the Pioneer newspaper.

The book, Age of Videots, is a product of that desire or passion. His appointment as Director of Press to the then Governor Victor Attah of Akwa Ibom State moved Udeme from the realms of a political reporter to that of a political protégé. Today, when he talks politics, he does so with practical insights. He even sought election to the federal parliament at a time and got so bruised that he is still recuperating. Maybe, one day, he will write about that experience.

This is great! Nigeria should not joke with such a man as this

Such a man as this should not be forgotten. We love Nyakno Osso